Defining the specificity of science fiction produced in Latin America has been a topic that has sparked numerous debates over several decades. Opinions have ranged from defending the originality of science fiction (from now on SF) from the region with respect to the Anglo-American models of the genre to flatly denying the science-fictional condition of much of this production, a position sometimes adopted even by critics and writers from this geographical area. Traditionally, two general terms have been used to characterize the specificity of Latin American SF: “soft science fiction” and “hybrid science fiction.”[1] However, recent theoretical developments may allow approaching this topic from other angles. The theory of SF has produced other concepts, apart from the usual ones of hard and soft SF, to cover the whole of a production that, even in the field of its origin, is much more varied and multiform than is usually assumed. In this sense, perhaps the most widely used term in the last two decades has been slipstream. But to this, we could add those of “genre SF,” “fabulation,” and “fantastika,” proposed by the authors of The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. These concepts, while not necessarily allude to the margins of SF, allow us to put some debates about the genre in better perspective.

In the following pages, I propose to examine the initial production of SF in Cuba, that is, the first works published in the 1960s, in what several authors recognize as the first of the periods of national SF, focusing specifically on the relationship it maintained with the international paradigms of the genre. For this, however, we must establish some general theoretical frameworks.

The specificity of Latin American SF has to do with how the international reception of Anglo-American SF took place. Some critics have gone so far as to claim that these alternative forms are not “true” SF, especially those who defend the centrality of so-called “hard SF.” However, countries with an established literary tradition could not limit themselves to merely copying the new type of SF that began to spread from the United States from the 1950s onwards. The process of assimilation posed several problems. The first—and very important in Latin America—was the absence in the great majority of countries of a large market for SF, that is, a market for magazines and books of this genre. This was more important than the oft-mentioned issue of techno-scientific development. Because, after all, most of the authors of the pulp magazines had no scientific background. What they did have at their disposal was a niche market for their fantastic “super-science” stories. They learned to write SF by imitating the successful formulas of other authors. This would continue to be the case, even to this day, although it is true that the scientific knowledge of writers increased from the so-called Golden Age onwards.

In the absence of a specific market for SF, writers from other countries—and not only those from Latin America—had to choose as a strategy to adapt their writing to the already existing market. That is why these works are a kind of hybrid between some conventions and themes of Anglo-American SF, on the one hand, and mainstream styles and treatments, on the other. In addition, from Anglo-American SF, they tended to choose as models the authors who came closest to this ideal, in particular Ray Bradbury. Long contested in the more orthodox circles of American SF, Bradbury was, nevertheless, the most widely read and influential of the SF writers in Europe and Latin America in the 1950s and 1960s. In general, examples of “soft” SF and other styles that departed from hard SF in the strict sense were favored.

Reading the works of some early Latin American SF writers, we note that they also did not establish the clear separation between SF and fantasy that had become an article of faith in Anglo-American SF during the Golden Age. Early Latin American SF sometimes seemed a variety of fantastic literature with some contributions from the poetics of SF. There were also important contributions from the absurd and magical realism. Some Latin American writers sought to be recognized as SF authors and at the same time as writers in their own right, with a work homologous to that of their mainstream colleagues. This was difficult to achieve through a loyal affiliation to hard SF of the Campbellian type, with its typical tendency to subordinate style to content and its rejection of markedly personal poetics.

Hernández Artigas: The Forgotten Pioneer

The emergence of SF in Cuba in the sixties can only be a surprise for those who are not familiar with the evolution of Cuban and Latin American literature in general. By this time, Cuban literature had reached a degree of sophistication and quality that placed it among the first in the continent. The cultivation of SF moreover took place amid a boom of fantastic literature in Cuba, a curious phenomenon still not well explained and that would not be repeated. The approach of a handful of young authors to this genre must be seen within the framework of a great opening of horizons in Cuban literature and the strengthening of its international or cosmopolitan component. Around this same time, SF or, to be more precise, the new style of SF that emerged from the hand of John W. Campbell and his group of authors during the so-called “Golden Age of SF,” was having a great impact at the international level. Cuba was simply joining this wave. Cuban readers were introduced to this new SF thanks to the translations of short stories that appeared regularly in widely circulated magazines such as Carteles and others. Some students also experienced it firsthand during their stay in the United States. It is no coincidence, for example, that several of the first authors of this genre in Cuba resided for some time in the neighboring nation to the north. The peculiar fantastic literature written in Argentina by writers such as Borges and Bioy Casares was also well known in our country. In fact, some of these early works bear a certain resemblance to the contemporary Argentine production of SF and even of later decades, although it could also simply be a case of “convergent evolution.”

In a study of the beginnings of SF in Cuba, one cannot overlook the important work of translation and dissemination of the genre carried out from the popular magazine Carteles in the late fifties by José Hernández Artigas, which has fallen into undeserved oblivion. Already in Rogelio Llopis’ prologue to his essential anthology Cuentos cubanos de lo fantástico y lo extraordinario, dated 1967, we can read the following opinion: “In the persons of Oscar Hurtado, poet and prologue writer of long and commented performance in Cuban literature, and José Hernández Artigas, narrator admired by Cortázar, the genre had its true Cuban precursors, both in the informative and creative spheres.”[2]

This fact is ratified by the Diccionario de literatura cubana (Cuaderno de trabajo), of 1968—which was never published and should not be confused with the later one of 1981—, which includes an article on Hernández Artigas where, after referring to his translation work, it is stated that: “His artistic work, scattered in magazines, is also centered on science fiction stories, which appeared around 1957 in Carteles, so he can be considered one of the pioneers of the genre in Cuba.” His informative work on the genre was undoubtedly impressive. In 1958 alone, forty-two science fiction stories by American and British authors were published in Carteles. These stories, mostly translated by Hernández Artigas, who invariably signed with the initials “H-A” of his surname, appeared in a section of their own, entitled Science-Fiction, always accompanied by a careful work of illustration and design, mainly by Manuel Vidal and Jesús de Armas. The section began in July 1957 with Ray Bradbury’s short story “Zero Hour,” accompanied by a brief text, written by Guillermo Cabrera Infante, which may have been intended to serve as an introduction to the new section and which I would like to quote in full:

Zero hour has arrived. Carteles enlists its readers for the voyage to infinity. The ship is before you. It is piloted by Ray Bradbury, explorer of multiple strange worlds. He is assisted, for the benefit of readers who speak Spanish and not the language of space, by H. A. whose mysterious acronym seems to enclose in a literary capsule the explosion and implosion forces of atomic-hydrogen bombs. This is the start of the journey. The adventure in outer space has begun.[3]

The section continued until the beginning of 1959, after which it became irregular. Artigas died in a tragic accident in Havana around 1971 or 1972.[4]

In literary supplements of the newspaper Revolución we could find two SF stories by Hernández Artigas: “Onomástico” and “Dios igual a hombre por velocidad-luz,” both from 1959. In issue number 17 of 1963 of La Gaceta de Cuba, “Cósmicas” was published (also signed “H-A,” as in Carteles), which includes three short stories: “Caso: Ekaterina Romaninova, ‘Señorita Terra 2938,’” “Caso: D Mirgz, Planeta Achernari, Sol 99-9-RT-J,” and “Error de Mickey.” They are short pieces of humorous SF among which the third one stands out, in my opinion, one of the best stories of the genre written in the sixties in Cuba and which, if it had not been forgotten, would be considered a classic today.[5] These stories inaugurated the line of black humor in Cuban SF that would later be followed by several authors.

It is also possible that Hernández Artigas had already published some SF stories in Carteles in 1958, but using pseudonyms that we have not yet been able to confirm. For all these reasons, I believe that the widespread belief that modern Cuban SF began in 1964 should be rectified. In reality, its origins date back to 1958 and are related to the activity of this forgotten writer. And, if one takes into account that “El día que Nueva York penetró en el cielo,” by Ángel Arango (a story that, by the way, appeared in the same Carteles Science-Fiction section) can only partly be considered a SF story then the priority of having published the first modern SF story in Cuba probably belongs to Hernández Artigas.

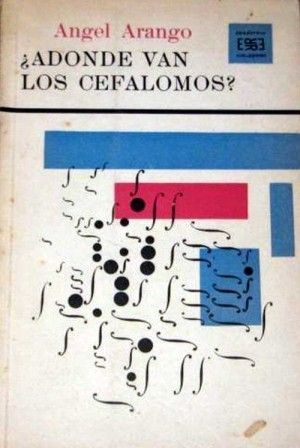

In 1964, the first books of Cuban SF saw the light of day: ¿Adónde van los cefalomos? by Ángel Arango, La ciudad muerta de Korad (poems), by Oscar Hurtado, and Cuentos de ciencia ficción, with a selection and prologue by Hurtado himself.[6] In the following years, books and isolated stories by other authors were published, the most important of which were the fix-up or cycle of stories by Miguel Collazo El libro fantástico de Oaj (1966) and the novel El viaje (1968),[7] while Ángel Arango enriched his bibliography with the short-story books El planeta negro (1966), Robotomaquia (1967) and El fin del caos llega quietamente (1971).[8] Besides this, some important stories appeared in magazines and in the anthologies Cuentos de horror y misterio (1967), by José Rodríguez Feo, Cuentos cubanos de lo fantástico y lo extraordinario (1968), by Rogelio Llopis, and Cuentos de ciencia ficción (1969), by Oscar Hurtado.[9] For reasons of space, it is not possible to talk here about all the authors of this period, so I have chosen to concentrate on the works of three of them: Ángel Arango, Miguel Collazo and Juan Luis Herrero.

Ángel Arango: Science Fiction and “Something More”

Of the three SF books published by Ángel Arango in the sixties the closest to this genre is perhaps the first. The story that gives the book its title, “¿Adónde van los cefalomos?”, is clearly SF, where one can even observe the use of the “cognitive estrangement” that Darko Suvin postulated as essential to this genre. In “El arco iris del mono” the lovers in the story are radiation mutants, a classic SF motif.[10] They depend on technology to communicate, a theme—that of technological dependence and its consequences—that will also be present in his later books. The story is more about the fate of humanity than the individual fate of the characters, another characteristic of SF. These characters, moreover, are typically placed in extreme situations. The main difference between these stories and the average Golden Age tale lies in the greater emphasis on style that we find in Arango.

The books El planeta negro (1966) and Robotomaquia (1967) mark a change. Let us dwell on the stories “El planeta negro,” “El gasrobot.” and “El enigma.” “El planeta negro” is one of the most interesting stories by this author. A ship arrives on an unknown planet. They immediately realize that they are facing a cosmic anomaly. The group of scientists on board begins a series of investigations and experiments to determine the nature of the new world but inexplicable facts accumulate: there are mysterious energy losses, the biological samples left on the surface disappear, and they find out the relief of the planet is completely uniform, which leads them to call it Monotony. Successive explanatory hypotheses are issued and discarded one after the other. Finally, they have to leave without finding out absolutely anything about the planet. But when they return to the base, they discover they have lost half of their body mass. The story ends with a lapidary sentence: “And he understood that, irremediably, they had left half of their life and body in Monotony.”

Here Arango is rewriting the codes of the genre. The initial situation of the story presents us with a typical SF scenario: the exploration of an alien planet or world that poses an enigma. We can think, to cite the first example that comes to mind, of Larry Niven’s Ringworld but the subsequent development subverts this premise, for it is never really understood what the Black Planet is. In typical SF, anomalous events demand a rational explanation. Even events that, at the beginning of a story are presented as apparent instances of a supernatural cause are given a scientific explanation at the end. Inexplicability is characteristic of another genre: the fantastic, not of SF. Already in an article on hard SF in Cuba Raúl Aguiar, commenting on this same story by Arango, alluded to this refusal to explain, which sets “El planeta negro” apart from this style of SF.[11]

“El gasrobot”, from Robotomaquia, is a story similar to this one, although at first glance it may not seem so. The strange robot of the title, found on Pluto, seems to be defined by negations. Little can be said about it other than that it fascinates children thus associating it with the realm of the spontaneous and the pre-reflective, rather than with adult rationality. The other thing that is affirmed with certainty is that it is a gas but this adds to the lack of definition, since gas is the amorphous state of matter par excellence. The gasrobot escapes all definitions and explanations of adult, rational, science-based society. In this sense, the textual strategies of the story approach the fantastic, as no explicit clarification is ever offered as to what the gasrobot was and why it disappeared. The inexplicability of the gasrobot sets this story apart from the norms of SF. In what sense, then, can the story be considered as belonging to that genre? Beyond the use of a setting set in the future, I think the main thing is that it describes a world radically transformed by science and technology, where travel to the ends of the solar system has become possible. The story, moreover, resorts to a typical SF motif: the discovery in a faraway place of an enigmatic object that must be brought back to Earth for investigation. From here the text develops a conflict, very skillfully presented, between the generic expectations of SF and the norms of the fantastic tale that burst into the story destabilizing it. The gasrobot eludes all explanation, it is more elusive and mysterious than the Tao, it transgresses all explanatory rationality.

If we compare “El planeta negro” with “El gasrobot” we will see that they tell similar stories in essence. Both tell the story of an encounter with an unknown phenomenon that defies all interpretations and is like a semantic frontier where meaning collapses. In “El gasrobot” this is presented in a discursive style (hypotheses are issued) while in “El planeta negro” it is narrativized in the form of successive failed experiments, which seek to explain the nature of this unknown something.

The story “El enigma,” from Robotomaquia, is also related to the previous texts. Here the inexplicable fact is the arm of a man protruding from under a closed door. The investigation of this mystery is carried out by a robot. Its meticulous examination of the interior of the room is reminiscent of the production of explanatory hypotheses in “El gasrobot” or the fruitless investigations of the scientists in “El planeta negro,” i.e.: it is a closed room, there is no place to hide, there is not enough air to breathe, and so on. The robot finally leaves, unable to find an explanation, and the story ends as it began: a man’s hand reappears from under the door. In this extremely short story, the reader is forced to fill in the blanks left by the author. We are probably facing a robotic culture, where humans no longer exist, except as ghostly presences such as those presented in the story. The robot’s failure to explain the illogical but tenacious presence of the human arm again highlights the divorce or disjunction between two orders, in this case, the rational and the irrational.

In “El planeta negro” the otherness of deep space is not susceptible to being unveiled. We are faced with an ontological impossibility. It is as if we were being told that the universe is a place too alien to be understood and assimilated in human terms since describing and explaining the Other is a way of subtracting something of its otherness and incorporating it into the human universe. In “El gasrobot” society does not have in its cognitive maps a box where to place the small robot native of Pluto. In “El enigma,” the presence of the human, its way of being, is a mystery that falls beyond the intellectual capacities of the investigating robot. These stories thematize the idea of “the unassimilable,” that which continues to tenaciously maintain its otherness, and the failure of the enterprise of building bridges to the unknown.

The idea of the radically alien universe also appears in Arango’s anthological story “The Cosmonaut,” although here the difference is not articulated on the ontological axis but on the cultural and biological. The proverbial “first contact” is not possible, despite the goodwill of both parties, because the communicative barrier between the species cannot be overcome. In all these examples, we can see that the author is in dialogue with the SF of the Golden Age, with its characteristic technological optimism, its stories of first contact, and its successful space explorations. Arango uses these same tropes and themes but recycles them to put them at the service of conveying a different message. They are stories permeated by an anti-technological and anti-scientific ideology, most likely descended in a direct line from Ray Bradbury.

Both “El planeta negro” and “El gasrobot” and “El enigma” are stories related to SF. But they are not simply “genre SF,” they are SF “and something else.” This hybridization strategy allows the use of several typical SF resources but mixes them with a literary tradition that makes them more familiar to part of the Cuban reader of the sixties. There is a mixture of the conventions of SF with those of the fantastic, which is a form of mainstream literature. From SF Arango takes some of his most typical motifs, such as robots, mutants, non-terrestrial planets, aliens, holocaust, accelerated evolution, etc.

In his review of Arango’s first book, entitled “Einstein y los cefalomos,” the writer Juan Luis Herrero rejected the possibility of considering Arango a pessimist: “Pessimism? No, warning of an inevitable reality if the world does not end up agreeing with the idea of peaceful coexistence. This warning is embodied in the stories of ¿Adónde van los cefalomos? It is the concern of a writer aware of the moment in which he lives. Angel Arango is not a pessimist, but confronts us with the absurdity of man trying to destroy himself in a suicidal war.”[12] As Peter Nicholls notes in the article on this same subject in The Science Fiction Encyclopedia: “any categorization of sf stories into the optimistic and the pessimistic is so imprecise as not to be greatly useful.”[13] The problem lies in how exactly to define “pessimism,” as well as the ever-present possibility of reading a gloomy story as a warning (which is what Herrero was doing in his review). But these Arango stories must be seen against the backdrop of the technological utopianism, “technophilia,” and teleology of progress typical of American Golden Age SF. It is in this sense that Arango’s SF can be categorized as pessimistic. What interests us above all in using this term is to underline its difference when compare to Campbellian and Golden Age SF. Incidentally, even his well-known short story “Un inesperado visitante,” although it contains social motifs and the protagonist presumably belongs to a more advanced society of the future, also participates in this pessimistic vision, since ultimately all the character’s efforts are sterile and the truth he tries to convey is distorted.

Theoretical Parenthesis: Genre Science Fiction and “Fabulation”

At this point it would be good to open a parenthesis to examine some theoretical concepts. To better understand what authors like Arango, Collazo, and Herrero were doing in the sixties, it is useful to keep in mind the concepts of “genre SF” and “fabulation” used by John Clute and Peter Nicholls in their Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. “Genre SF” is what is usually understood by SF, the works that fans, readers, and critics of the genre “instantly recognize” as members of that category. Genre SF is differentiated from-and contrasted with-both mainstream literature, and other forms of SF and fantasy, such as SF written by mainstream authors, or the products of magical realism, absurdist SF, and slipstream.[14] In a word: genre SF is what fans recognize as “true SF.” John Clute points out that, although SF is often believed to be opposed to the realist literature of the 19th century, in reality “genre SF […] is essentially a continuation of the mimetic novel, which it may have streamlined and made more explicitly storyable, but certainly did not supplant.”[15] In the article “Mainstream Writers of SF,” also in the aforementioned encyclopedia, Peter Nicholls refutes the belief, widespread in the SF media, that SF is really an alternative to realist fiction:

This is the belief that sf, by escaping from the here-and-now of realist fiction, was to be greatly admired as spearheading a new, less constrictive, more imaginative nonrealist mode. Sf, on the contrary, lies at the heart of the realist mode; its whole creative effort is bent on making its imaginary worlds, its imaginary futures, as real as possible. The experiments in breaking down realist or “mimetic” fiction were taking place elsewhere; fabulations are fictions distrustful both of the very tools with which the world can be made known, words […], and as to whether the world can in fact be known. A quite extraordinary number of fabulators use sf motifs, but in the construction of works whose foregrounding of their own artifice is opposed in style and feeling to the traditional mimesis of genre SF.[16]

Clute concludes his article by citing a long list of fabulist authors, including Bioy Casares, Borges, Burgess, Burroughs, Dino Buzzati, Calvino, Thomas M. Disch, Umberto Eco, Carlos Fuentes, Kafka, Haruki Murakami, Thomas Pynchon, Salman Rushdie, Norman Spinrad, Gene Wolfe, etc. Although, for his part, Peter Nicholls notes that SF also produced its own fabulist writers, among whom he cites such well-known ones as J. G. Ballard, John Crowley, Thomas M Disch, M. John Harrison, Michael Moorcock, Lucius Shepard, John T. Sladek, and Gene Wolfe, so that, he concludes, “here too the distinctions between genre and mainstream SF are elusive.”

I do not mean to imply that Arango or any other Cuban author should be added to the roster of fabulist writers. What interests me most about Clute and Nicholls’ ideas is the light they shed on the characteristics of genre SF and, especially, their thesis that SF is really a continuation of nineteenth-century mimetic literature. Because if this is so, then it must be concluded that some of Arango’s stories are a departure from SF understood in that way.

In Robotomaquia we already notice a change in Arango’s SF that heralds the style of the “legends” of his next book, El fin del caos llega quietamente. This change consists of the stories moving towards the form of fables, shedding the extrapolative elements that appeared, albeit in limited quantity, in his first book. This is especially so in “El gasrobot,” “El enigma,” and “Sol-ventana-pájaro.” There is an important difference between a story like “El eje del diablo” and “El enigma.” The latter is so orphaned of extrapolative elements that it moves in the direction of the fabulous and the fantastic. The human arm sticking out from under the door is a detail that, by eluding any rational explanation, invites metaphorical readings. Compare this with a story like “El arco iris del mono” (from his first book), where, despite its poetic style, it must be interpreted literally that the protagonists are mutants who would not be able to communicate without their space suits. These other stories move in the direction of Clute and Nicholls’ “fabulation”: they are stories where an opacity is manifested, not the faith in a reality external to language typical of Campbellian SF. They depart, to some extent, from the conventions of mimetic fiction which, as these critics rightly point out, are at the heart of genre SF. The world of “El eje del diablo” (one of his most classic SF stories, also from his first book) is a possible world, in the special sense in which this concept of “possibility” is handled in SF, that is: “not impossible in principle.” But the world of “El enigma” and “El gasrobot” does not exist outside the act of enunciation of the story, and this is no longer common to the narrative conventions of typical SF, or, in other words, of genre SF. “El eje del diablo” demands a literal reading in order to be understood. That is, within the reality presented by the story it must be accepted that Martinez’s character built a highly advanced robot, that this robot can think, and that he is puzzled because his creator demands that he cry. It must also be read on a literal level that the children torment the robot and that the robot is attracted to Martinez’s wife. One must also accept the insinuation that he killed his creator (“I made you inactive,” it says) and the final allusion, with which the story ends: that it intends to turn the woman into a kind of robot. On the other hand, in “El gasrobot” or “El enigma” we would get a very distorted understanding of them if we were to read them literally. The irruption of the impossible, the irrational or the inexplicable pushes the story in the direction of metaphor, symbol, and the fantastic. “El eje del diablo” is SF, but “El planeta negro” and “El gasrobot” are SF “and something more.”

Miguel Collazo: From Science Fiction to Fantasy

In the case of Miguel Collazo, we can observe an evolution to some extent similar to that of Arango. His first work, El libro fantástico de Oaj (1966), is closer to science fiction than his second foray into the genre, El viaje (1968). The first book—which he began writing around 1964—consisted of a series of interrelated stories and vignettes, in a manner clearly inspired by Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles. However, from the American writer Collazo mainly took this technique, not his vision of the world and literature. Most of the stories are set in Havana in the 1950s and the author reproduces the language and behavior of the popular sectors of the city of Havana.

The stories in El libro fantástico de Oaj are quite close to SF, although they are often examples of satirical and humorous SF, as Virgilio Piñera already noted in his review of the book. Piñera praised in this collection precisely the use of humor and even creole choteo (perhaps he was the first to use this concept about Cuban SF). The famous Cuban writer and critic also called attention to the existence of two types of SF:

Although I am not an addict to such literature and much less a connoisseur, nevertheless it seems to me that there are two kinds of science fiction. The first is the one cultivated by writers who are also scientists, or scientists that also writes. Such, for example, the Englishman Arthur Clarke. The second is that of writers who are not scientists but who cultivate science fiction. The most prominent of all of them is Ray Bradbury with his powerful fantasies.[17]

Actually, here Piñera was delineating the well-known difference between “hard SF” and “soft SF,” while placing Collazo within the latter. El libro fantástico de Oaj has, as I said, a marked satirical and humorous character, and Collazo’s Saturnians cannot be considered examples of serious speculation with possible aliens, as in hard SF. In the book, they represent future and technological otherness and, implicitly, possible social change and the modernizing project. Their contact with the terrestrials (with the inhabitants of Havana, actually) can be read metaphorically as the encounter between the present of an underdeveloped society and the world of the future, more socially and technologically advanced. This latent tension in the book is evident, for example, in the story “El amor de Yarnoo,” which recounts the love affair between a Saturnian woman and a typical Havana “chuchero” of the 1950s (a sort of pachuco, so to speak). The relationship is almost impossible, due to the extreme cultural and biological disparity between the lovers. At the symbolic level, we are faced with the clash between underdevelopment, on the one hand, and a modernizing, future-oriented ideology and the transformation of human nature, on the other. We find the same subtext in the next story, “El orate andrajoso”, where the author puts these words in the mouth of one of the characters: “It was precisely guys like that who prevented the arrival of the Saturnians,” which is like saying: those who prevented the arrival of the future. This brief analysis allows us to see that Collazo uses in his book the satire and the “cognitive estrangement” that Darko Suvin considered essential to the genre so the book approaches some typical conventions of SF, although, at other moments, it happily transgresses them, especially when it renounces to offer a rational validation of the biological nature of the Saturnians.

In the April-June 1967 issue of Unión magazine, the short story “Gasificaciones.”[18] Dated “Paris, October 1966,” added in parentheses: “From the Libro de las invasiones de los terrícolas, still unpublished.” It was a story written in a style reminiscent of that of his first book, of which it was probably to be the sequel (as was, probably, “El laberinto de Mñes,”[19] another story with a “Saturnian” theme published in Bohemia also in 1967).[20] But instead, Collazo would publish the following year a novel with a completely different theme: El viaje.

Constructed through numerous allusions and symbols, El viaje is a novel set in the rather abstract space of the planet Amber. Written in prose captivating in its poetic beauty, the book tells the story of several generations of descendants of a group of astronauts who tried to settle on the planet Amber. For some unclear reason, this attempt at colonization failed and ended in social collapse, a theme, by the way, dear to classic Anglo-American SF, which we find, for example, in authors such as Robert Heinlein, Daniel Galouye, and Brian Aldiss. The characters have forgotten their origins and why they find themselves in Amber, where they live an elementary and irresponsible life, without telos. The plot of the novel seems then to revolve around the slow and painful process, made of groping and intuitive searches, by which these people gradually regain their ability to return to this initial purpose and set out again on the path of human history, to which the symbolic concept of the “journey” alludes.[21]

In El viaje the connection with SF is even more tenuous than in the previous book and its renunciation of the norms of mimetic fiction, which as we saw Clute and Nicholls considered essential to SF, is radical and complete, for the author makes no attempt to communicate verisimilitude to the imaginary scenario. The only possible reading is metaphorical and symbolic. Among the science-fictional motifs that managed to make their way into the book, it is also worth mentioning—besides the aforementioned social collapse—that of the mutants, already noted by José Alejandro Álvarez Moret in his reading of this novel.[22]

Collazo continued publishing stories in La Gaceta de Cuba, but these were already of fantasy: “El sapo” (1969) and “En el pequeño balcón del señor” (1970).

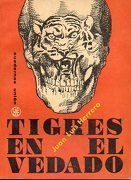

Juan Luis Herrero: Narrator of Violence

Juan Luis Herrero’s brief oeuvre is interesting because it does not participate in the tendency toward hybridization seen in Arango and Collazo, at least not in an evident way, to which we will return later. Rather, it is oriented towards the norms of “genre” SF, which is ahead of the SF that would later be written in our country. According to data found by researcher Ricardo Hernández Otero, Herrero was the son of the poet Gustavo Galo Herrero. In 1951, he traveled to the United States and lived for three years in Tampa, Miami and Jacksonville. On his return to Cuba, he began studies at the Manuel Márquez Sterling Professional School of Journalism and the Law School of the University of Havana but did not finish them. He was a theater actor, singer and director of a musical group, employee at the Editorial Nacional de Cuba, and cartoonist. He also worked as a librettist, commentator, and critic in radio and television. He obtained a mention in the 1967 David Award with his book Tigres en el Vedado.[23] He published stories and reviews in El Mundo, Juventud Rebelde, La Gaceta de Cuba, Unión, and Granma. In 1968 he worked as a publicist for the Instituto del Libro. He emigrated around 1975.[24]

Apart from his best-known stories, “No me acaricies, venusino”[25] and “Ese ruido como de piedras que caen,” we have been able to read five more stories. Cuentos de ciencia ficción, published in 1964 with a prologue by Oscar Hurtado, includes four of his stories. The first, “Levitación,” is fantasy, while the rest are science fiction: “Cromófago,” “Telequinesis,” and “Pilones, pilones y más pilones.”. Although this selection also included texts by Carlos Cabada and Agenor Martí, the only ones that offer real literary interest, despite being still immature, early works, are those by Herrero, something already pointed out at the time by Luis Agüero.[26] The most interesting is “Cromófago.” A new color appears on Earth, vielo, a primary color. The new color becomes fashionable and later becomes an epidemic. In time, vielo supplants green, then it also takes over yellow and blue. The sky, the trees, the grass, and the water take on the same color: “everything in a terrible, monolithic monotony.” Vielo is the “chromophage” of the title: a color that at first is well accepted, but gradually devours all the others. The protagonist, named Hally (the story is set in a place vaguely reminiscent of New York), hates the sky and wants to do away with it. Finally, after overcoming many misunderstandings, he creates a formula to destroy the new mutant color and restore the color gamut. “Cromófago” is written in a satirical style and is also probably the first Cuban dystopia, although the social theme that defines dystopias is represented here by the fanciful idea of “monolithic” physics, which only admits one color. The end of the story represents the return to diversity. The idea behind the story had potential but is squandered by a failed execution.

In 1966, the magazine Unión, in its July-September issue, dedicated a brief section to Cuban SF in which a short story by Herrero appeared entitled “Las moscas.”[27] In the interval of the past two years, the author has made great advances in the mastery of his craft as a storyteller; in fact, his style has undergone a radical mutation. The story takes place in the setting of the planet Wampuli (the same, by the way, of “Ese ruido como de piedras que caen”). The protagonist, apparently the last survivor of an expedition, has defied for two weeks all the deadly traps of the planet, such as the “crushing herbs,” the “meat-eating plants,” the swamps, and the wild beasts but has one last obstacle to overcome: the flies of the title, which, like everything in Wampuli, are apocalyptic and merciless. It is an almost minimalist story whose relevance rests solely on the skill with which it is told and which, unlike the tales in the 1964 selection, already exhibits stylistic traits similar to those of his two best-known SF stories.

“No me acaricies, venusino,” besides having a wonderful denouement, is interesting for presenting as its protagonist a repulsive, selfish, and xenophobic character, who does not hesitate to resort to murder to achieve his ends. But Herrero was not cynical: the conclusion of the story, by appealing to poetic justice, reaffirms ethical principles, and could even be said to be moralizing. “Ese ruido como de piedras que caen,” his perhaps most celebrated tale, was first published in 1967, and more than forty years later was included by Yoss in the historical SF anthology Crónicas del mañana (2009). Yoss does not spare praise for this story: “This story by Herrero has suspense and space terror of the good kind, with introspections of terrifying lucidity,”[28] a judgment we fully share. Nelson Román, in his book Universo de la ciencia ficción cubana (2006), also praises Herrero’s narrative skill and includes this story in his list of “milestones” of Cuban science fiction. In this story, the most evident conflict is the one that confronts the astronauts with the alien monster they find on the planet Wampuli. But there is another conflict in the background: the one that harasses the protagonist, who in order to save himself devises the stratagem of using two of his companions as bait, which he justifies because they have lost their minds anyway, and he only has one charge left in his pistol. As a curious anecdote, I add that the author himself told his friends that this story had been inspired by a house located at 23 and 2, in Vedado, where, according to the neighbors, strange noises and sounds could be heard, which made it a sort of “haunted house.”[29] Since the story itself does not have a supernatural theme, it can be assumed that the detail that went into the story was the “noise of stones” referred to in the title.

There is an element that links these three stories: the theme of violence connected to a kind of tragic vision of existence. In “Las moscas,” the protagonist ultimately sees no other way out than suicide; in “No me acaricies, venusino,” the protagonist kills his companion and tries to do the same with the Venusian of the title; and in “Ese ruido como de piedras que caen,” he sacrifices two of his astronaut colleagues to save his own life. Also common to all three is the ultimate futility of the characters’ efforts, evident in the last two stories, but also in “Las moscas.” This thematic component sets his fiction apart from the rest of the Cuban SF authors of the time and places it on a separate plane. Herrero’s tone in these stories is realistic, direct, and rough, unlike Arango and Collazo, who tend to literary stylization and poetry. How to understand this? The explanation, in my opinion, lies in the fact that Herrero had begun to write realistic fiction and, within this, he ascribed to the current that would be known as “narrative or style of violence.” This is what Eduardo Heras León explicitly states in the review of his first book, Tigres en el Vedado, when he places him as a follower of the narrative of violence, represented at that initial moment by Jesús Díaz and Norberto Fuentes.[30] For his part, Herrero, in an interview for La Gaceta de Cuba (after receiving a mention in the David Award), answered the question “Why violence? It worries me so much that I always deal with it when I write.”[31] I think it is safe to assume that in saying this he was also thinking of his SF work. In any case, there are subtle points of contact between his SF stories and his realistic fiction. The protagonists of the story “Tigres en el Vedado,” assassins in the service of the Batista dictatorship, are also examples of the ethically repudiatory character found in “No me acaricies, venusino,” while the protagonist of “Ese ruido como de piedras que caen” is reminiscent of the characters who must make difficult, agonizing ethical decisions in stories like “El chota,” “Acuérdate de Ramón Rodríguez,” and “Isla de Pinos.” Herrero also transferred some of the techniques of his realistic fiction to SF, with which his writing took a great leap since the narrative of violence was characterized precisely by bringing a renovating air to the way of telling. Even the synthetic beginning of “Ese ruido como de piedras que caen” (it begins: “That night terror started”) could have come from that other aspect of his work, and the same can be said of the beginning of “No me acaricies, venusino” (begins with the denouement). So even in Herrero, behind a relative closeness to genre SF, we can find a formula reminiscent of the principle of “SF plus something else,” in his case: “SF plus narrative of violence.” In SF Herrero found a symbolic space where he could deal, from another angle, with the themes of violence and cruelty that disturbed him. The encounter of these techniques and thematic obsessions with the conventions of SF produced unexpected results.

Summarizing, some general characteristics of this initial stage of Cuban SF are the following:

- Imperfect mastery of the conventions of genre SF.

- Hybridization strategies, which may be (partly) a consequence of the above: to give literary relevance to the story, procedures imported from the mainstream are resorted to.

- “Soft” SF. Little or no scientific content in the story. No interest in bringing speculation into the field of scientific ideas.

- Tendency towards the fantastic and poetic stylization.

- Reduction over time of the scientific-fictional content of the stories.

The originality of this early Cuban SF has been questioned, as it was supposedly strongly influenced by Anglo-American models.[32] But this, as we have seen, is not the case. Cuban SF was trying to carve its own path by hybridizing the SF of the Golden Age with approaches coming from high literature, which is very evident in the cases of Arango and Collazo. Their models were foreign because SF was not invented by Cubans. They can be criticized for not having achieved all their objectives, but not that they were passively following the path of others. If they overdid something, it was their excess of originality.

Sometimes people have wanted to see a relationship between this early Cuban SF and the so-called New Wave of science fiction. But I believe that these similarities if they exist, are due to the tendency to hybridization typical of our SF, which gives it a more “literary” character, and not to an influence of the Anglo-American authors representative of this current of the sixties. Something similar can be observed in other Latin American SF authors.

Decline and End

Towards the end of the period, and specifically from 1968 onwards, there was a slowing down of the momentum of this early Cuban SF (a fact already noted a few years ago by Javier de la Torre).[33] Arango’s last SF book was Robotomaquia in 1967 since his 1971 book is a fantasy book. Collazo takes a turn in his fiction with El viaje, from 1968, and not precisely in the direction of getting closer to the poetics of the genre. That is to say, it is a good novel, but its link with SF is more tenuous than that of the stories that preceded it. No other stories by Herrero are known after 1968. The most relevant facts for the development of SF in Cuba in these years are the publication in 1969 of the anthology Cuentos de ciencia ficción, by Hurtado (which also included stories by Cuban authors), and the appearance of the titles of the Colección Dragón, as well as some isolated curious event, such as the publication in 1970 of “El jardín del tiempo,” by J. G. Ballard, in translation by Rogelio Llopis for the magazine Unión, where also saw the light around that time “Los electropaladines” by Stanisław Lem (and let’s add some stories of the genre appeared in Bohemia). Changes were taking place in the cultural atmosphere of the country that did not favor, for the time being, the cultivation of fantasy genres. Exhortations to cultivate social realism and to write works that “reflected” the transformations in Cuban society were becoming more and more peremptory. Arango’s story “La bala en el aire” contains reflections by the protagonist that could be interpreted as a self-critical distance taken by the author himself about his initial production: “All his ingenuity served only to write sad, dull things, with a thought between life and death.” The end of the story evokes the idea of the social responsibility of literature and of the writer, which will become dominant in the following period: “What are all the pages of the world worth if they cannot sow the Earth with dreams…?” This tone did not appear in his first books, which leaned towards pessimism, irony, and black humor. Another striking fact is that new authors were not joining the movement either. Perhaps the only exception was Ramón Rubio, who in 1970 published in La Gaceta de Cuba the short story “El planeta silencioso,” although everything seems to indicate that the author was of Chilean nationality.[34] Veiled criticisms of Cuban SF also began to appear, as in the back cover note of Otra vez en el camino, by Germán Piniella, a book published at the beginning of 1971. There we read: “At first sight, the stories of Otra vez en el camino could make us think of the so-called science fiction. However, we should not be confused: Piniella is not interested in robots, nor in ultra-civilized worlds, nor in people called Xwexz or simply X-54, like the classics of the genre [sic]; and their mediocre followers from underdeveloped countries, who write stories that generally begin: ‘he turned on the super-engine of the… […].’” If this was an allusion to Collazo and Arango, it backfired on the anonymous author of the poisonous note, because, not to dwell on it too much, the former is today recognized as a remarkable storyteller of the revolutionary era. On the other hand, it is striking that in order to praise the work of an author it was necessary to dissociate it from the SF genre… In short: even before reaching that fault line that constitutes the year 71 in Cuban cultural history, the SF movement was showing evidence of deceleration and ominous signs were floating in the air.

The causes may have been both external to the movement and internal, the latter due to the difficulties in producing a model of SF attractive to the mass Cuban reader, which was already beginning to emerge. The SF of the two most important authors, Arango and Collazo, was too complex to fulfill this task; their poetics were too personal. The books they wrote were closer to the mainstream than genre literature, demanding considerable effort on the part of the receiver, who had to be willing to engage in a sophisticated literary game. This is visible above all in Collazo’s El viaje but it is also the principle that informs stories like “El gasrobot,” “El enigma,” or “El planeta negro” by Ángel Arango. As early as 1969 Arango began to publish stories that he would include in his future fantasy book El fin del caos llega quietamente, such as “Las criaturas,” which first appeared in La Gaceta de Cuba. Also a few months earlier he had published “El profesor ha muerto,”[35] an interesting tale of experimental prose that seems to anticipate what decades later would be called slipstream and which marks a clear break with his previous SF style. Herrero alone was attempting to write SF of a different kind, but for some reason his literary career stalled or his interest in the genre waned.

Moreover, in the sixties, unlike today, SF was published in the most important magazines in which some of the stories by Arango, Herrero, Collazo, and Piniella originally appeared. But in the long run, this did not help the development of the genre as it probably encouraged some of the authors to leave SF behind to enter the mainstream. It is paradoxical, but, if we review the collections of La Gaceta de Cuba and Unión, this is what was happening: the science-fictional content of Arango and Collazo’s stories was decreasing over time. Currently, even Cuban authors of SF and fantasy with sophisticated literary proposals do not have regular access to these magazines, especially when what they write is SF proper, unlike what happened with the authors of the sixties. But by welcoming them in their pages, the magazines ended up changing the orientation of their writing; Cuban SF was absorbed by the mainstream.

In the following period, whose beginning is traditionally dated 1978 and which we usually call “SF of the eighties,” the way of writing SF in Cuba changed. Fabricio González is right when he points out that there is no continuity between the two stages and that “it can be said with a fair degree of certainty that no author of the second period took as a decisive influence another Cuban author of the previous period.”[36] The emphasis on realism and on “accessible” literature, which was accompanied by the retreat of Modernism and, therefore, of formal experimentation, favored, directly or indirectly, the development of a new type of SF, more realistic and somewhat closer to what Clute and Nicholls call “genre SF,” whose best example is the work of Agustín de Rojas, but which we also find in Daína Chaviano and other authors. Therefore, what happens in this second period is a re-foundation of Cuban SF, which, seen with the benefit of hindsight, was a very important fact.

However, the objections above should not let us lose sight of the fundamentals. The Cuban SF of the sixties offered, at least in its main writers, a proposal of high literary quality and planted the flag of SF in Cuban literature. This effort did not fall into oblivion; over time, it grew in the cultural memory and led to the emergence of the myth of a golden age of SF that had existed in the recent past, when suddenly the impossible became possible. And this ended up being perhaps the most important legacy of these authors for the future.[37]

Notes:

[1] On the topic of hybridity, cf. the interview with Rachel Haywood: “So some of the things that we scholars say about Latin American science fiction is that it has a tendency more towards hybridity with other genres, such as fantastic, horror, magical realism, than science fiction in the North. Although this is debatable, but it is one of the tendencies that is being noticed.” For the use of “soft SF” in relation to Latin American SF, see Roberto M. Lepori: “¿Quién le teme a C. P. Snow en la crítica de ciencia ficción latinoamericana? El enigma del género en el laberinto de una conspiración hermética,” Alambique: Revista académica de ciencia ficción y fantasia / Jornal acadêmico de ficção científica e fantasía: vol. 1: iss. 1, article 5.

[2] Rogelio Llopis: Cuentos cubanos de lo fantástico y lo extraordinario, Ediciones Unión, Havana, 1968, pp. 28-29. Actually, Llopis had already mentioned Hernández Artigas a little earlier in an article published in Bohemia, where he describes him as a “precursor” of SF in Cuba. cf. Rogelio Llopis: “Ojeada crítica al cuento fantástico,” Bohemia, September 30, 1966, no. 39, p. 34.

[3] Carteles, no. 28, julio, 1957, p. 92. The note was not signed, but in H-A [J. Hernández Artigas]: “Cósmicas,” La Gaceta de Cuba, no. 17, 1963, pp. 6-7, this text is explicitly attributed to Cabrera Infante.

[4] Personal communication from researcher Jorge Domingo Cuadriello.

[5] H-A [J. Hernández Artigas]: “Cósmicas,” La Gaceta de Cuba, No. 17, 1963, pp. 6-7.

[6] Angel Arango: ¿Adónde van los cefalomos?, Ediciones R, Havana, 1964.

[7] Miguel Collazo: El libro fantástico de Oaj, UNEAC, Havana, 1966; El viaje, UNEAC, Havana, 1968.

[8] Ángel Arango: Robotomaquia, Cuadernos Unión, Havana, 1967.

[9] Oscar Hurtado (ed.): Cuentos de ciencia-ficción, Ediciones R., Havana, 1964.

[10] Cf. Ángel Arango: El arco iris del mono, Letras Cubanas Publishing House, Havana, 1980. Selection that includes a good part of his early fiction.

[11] Raúl Aguiar: “Ciencia ficción dura en Cuba”, Qubit. Boletín Digital de Pensamiento Cyberpunk, no. 56, p. 4.

[12] Juan Luis Herrero: “Einstein y los cefalomos”, La Gaceta de Cuba, March-April, 1965, p. 25.

[13] “Optimism and pessimism”, SFE. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

[14] For a definition of slipstream cf. Paweł Frelik: “Of Slipstream and Others,” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 20-45.

[15] John Clute: “Fabulation,” SFE. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

[16] Peter Nicholls: “Mainstream Writers of SF,” SFE. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

[17] Virgilio Piñera: “El libro fantástico de Oaj”, Unión, July-September 1966, pp. 185-186.

[18] Miguel Collazo: “Gasificaciones”, Unión, no. 2, 1967, pp. 143-145.

[19] Miguel Collazo: “El laberinto de Mñes”, Bohemia, June 16, 1967, pp. 32-33.

[20] By the way, the illustration was by Manuel Vidal, the same who had illustrated many SF stories in Carteles.

[21] There are two important studies on El viaje: “Los misterios de Ámbar” (Korad. Revista Digital de Literatura Fantástica y de Ciencia Ficción, no. 21, April-June, 2015, pp. 13-23), by José Alejandro Álvarez Moret and, more recently, by Víctor Fowler: “Batallas de imaginación: el momento interior de Miguel Collazo”, “Caminos nuevos”, Editorial Letras Cubanas, Havana, [in editorial process].

[22] José Alejandro Álvarez Moret: “Miguel Collazo y El viaje, una novela cubana de ciencia-ficción”, Qubit. Boletín Digital de Pensamiento Cyberpunk, no. 81, pp. 32-34.

[23] Juan Luis Herrero: Tigres en el Vedado, UNEAC, Havana, 1967.

[24] Ricardo Hernández Otero: “HERRERO, Juan Luis,” Literatura en Cuba (1959-1998): Diccionario biobibiográfico de autores [Unpublished work of the Literature Department of the José Antonio Portuondo Valdor Institute of Literature and Linguistics], and Roberto Branly: “Herrero Sánchez, Juan Luis”, Diccionario de literatura cubana (Cuaderno de trabajo), Literature Section of the Institute of Literature and Linguistics [mimeographed text], 1968.

[25] Juan Luis Herrero: “No me acaricies, venusino”, in Rogelio Llopis (ed.): Cuentos cubanos de lo fantástico y lo extraordinario, UNEAC, Havana, 1968, pp. 292-304.

[26] Luis Agüero: “La ciencia, la ficción,” Bohemia no. 15, April 10, 1964, p. 23, review of Cuentos de ciencia-ficción. The critic also stated that most of the stories in the book “are as much in line with the genre as a tarantula on a strawberry ice cream could be.”

[27] Juan Luis Herrero: “Las moscas”, Unión, year 5, no. 3, July-September 1966, pp. 92-94.

[28] Yoss: “Juan Luis Herrero”, Crónicas del mañana, Letras Cubanas Publishing House, Havana, 2006, p. 45.

[29] Personal communication from researcher Jorge Domingo Cuadriello, who knew Herrero.

[30] Cf. Eduardo Heras León: “Herrero y sus tigres”, El Mundo, Wednesday, August 7, 1968, p. 2.

[31] Belkis Cuza Malé: “Los Premios David hablan para La Gaceta. Juan Luis Herrero,” La Gaceta de Cuba, no. 6, June 8, 1967, p. 69.

[32] See the prologue (unsigned) to the selection Cuentos cubanos de ciencia ficción, Editorial Gente Nueva, Havana, 1983. And also the judgment on Herrero in Nelson Román’s book: Universo de la ciencia ficción cubana, Ediciones Extramuros, Havana, 2005: “in all [his stories] he drags the heavy burden of the North American narrative influence…” (p. 48).

[33] “At the publishing level [writes this author], in 1969 Cuban science fiction suddenly disappeared,” cf. Javier de la Torre: “La ciencia ficción en Cuba y la etapa del quinquenio gris.” On the other hand, although Cuban stories appear in Hurtado’s 1969 anthology, it is likely that the volume was compiled during the previous year.

[34] Judging by his other published stories, he was an author who apparently moved more fluently in the realm of the fantastic. A case similar to that of Ramón Rubio is probably that of Franco Martín, a presumably Latin American author who in 1964 and 1965 published two SF stories in Bohemia.

[35] Ángel Arango: “El profesor ha muerto,” La Gaceta de Cuba, no. 69, January, 1969, pp. 14-15.

[36] Cf. Fabricio González: “Estrategias de legitimación de la ciencia ficción en Cuba: estudio de un fracaso,” in La Isla y las estrellas. El ensayo y la crítica de ciencia ficción en Cuba, Cubaliteraria, Havana, 2015, pp. 73-90.

[37] I am grateful to Cuban researcher and bibliographer Ricardo Hernández Otero whose help was fundamental in setting in motion the bibliographic research that underpins this work. Also, the researcher Jorge Domingo Cuadriello, who knew Juan Luis Herrero personally and also contributed important data on Hernández Artigas. My gratitude also goes to the specialists of the Fernando Ortiz Library of the Institute of Literature and Linguistics, Sonia Almaguer and Ydalmys Odalys Ríos Fernández.