In Roberto Echavarren’s writing, reflection on language is given, as Julio Ortega pointed out regarding José Lezama Lima, as a hyperreality with a baroque figure that entails an allegorical and symbolic expansion of signs, in an operation that simultaneously conceals and unveils their meanings. The poetic permeates the work, regardless of genre, since it is the “hybridization between genres,” as Eduardo Milán stated in the prologue of Aura Amara (1989), what the writing privileges. This strategy brings to the forefront the always controversial themes of sexual identity, the coercion of authoritarianism on individual freedoms, and the erosion of humanism in favor of collective alienation. Echavarren’s poetic, novelistic, essayistic, cinematic, and testimonial production addresses such complexities from the double gaze of Luis Buñuel’s severed eye, in a twist that creates several levels of meaning, where words are inscribed like signals on the skin of the texts. However, “this inscription is not possible without injury, without loss,” as Severo Sarduy reminds us, hence, the contents delve into the wound, shaking the readers and forcing them to confront their own fears, inadequacies, and uncertainties.

Poetic and Poetics

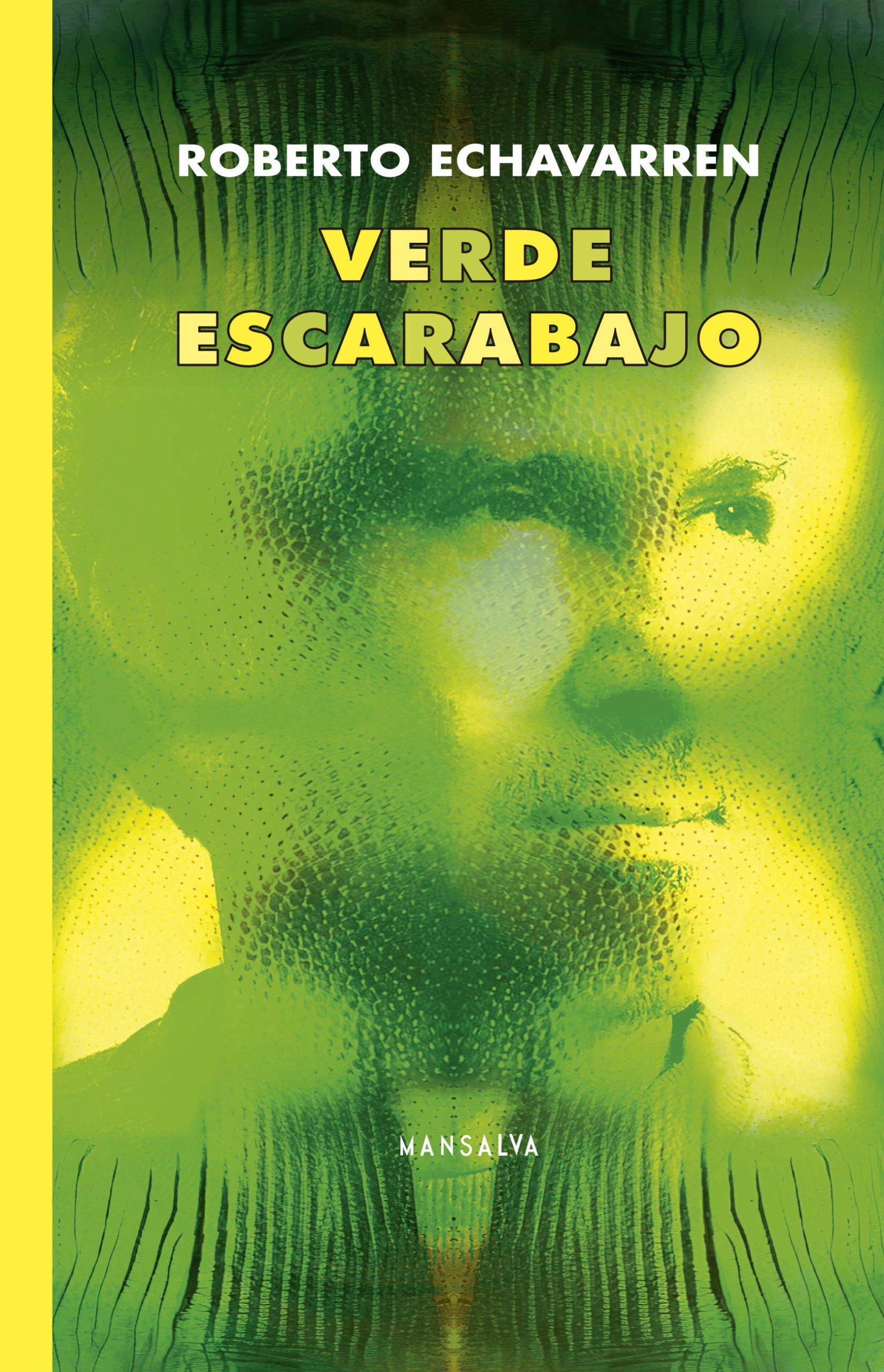

Echavarren’s poetic work written in the new millennium and primarily contained in the volume Verde escarabajo (2023), mirrors the strategies of his previous production, where the Neo-Baroque excess, characterized by the mutability and multidimensionality of meanings, permeates the texts. It also incorporates a historicism that inscribes the writing into events intended to shake a century marked by terrorism, violence against minorities, massive migrations, and political and social polarization.

In this sense, “Centralasia” (2014), a lengthy and breathtaking poem that opens the volume, traces a geographical, political, sensual, and religious journey through a Tibet occupied by the Chinese autocracy. This, from a self that narrates and recounts itself in the everydayness of the desire’s object, sharing with him a journey through a landscape where the wound, as product of genocide and invasion, remains open. Here, observation is made over a landscape emerging and fading away like frames of a watched, described, and possessed film, through a fragmented language illuminated with multiple meanings. The poem then becomes a large mosaic where words reflect reality fragmentarily; “broken mirrors where the world reflects itself shattered,” as Octavio Paz attests. The gaze becomes a substance, meant to gather the portions of what is left, and turn them into a stained glass that joins and separates, to emphasize the radicalization of the occupant, as reiterated by Echavarren in the prologue. “What was exotic in times past, our global world brings closer. What happens in Tibet is not foreign to the conscience of other peoples on the planet. The Chinese occupation has lasted more than half a century. Apparently one million Tibetans (out of a population of just seven million) have succumbed in the fighting or been liquidated by the forcible occupier.”

“Monte nativo” (2015) captures such radicality through a language that strips bare, drags, makes crack, and splits the landscape, erotizing it through descriptions of flora, fauna, and the marine world; all of this, framed by the urban tumult of Lisbon. In this city, the poet discovers and rediscovers himself through images that assail him on a tram, in a car, or amidst the organic elements of a beach where a stranded boat can also be an “Erect, translucent penis, / curved, violet peak, / drying quickly / under the sun that clouds it and brings it down.” Such strategy grants the text a density that defies the guidelines of modernity, where intolerance seeks to reduce certainties about life to mere falsifications, aiming to subdue it and control it.

The protest against the loss of meaning, the emptiness of sense, the absence of a coherent critical thought to organize chaos, mobilizes Echavarren’s writing. A writing that, as Guillermo Sucre emphasizes regarding Paz, “reproduces the conditions of a world that is no longer homogeneous, of a time that lacks a center; that is, of a reality that fragments and disintegrates.” This is echoed in “La guerra de Ucrania” (2022), the extensive poem with which Verde escarabajo concludes, centering a dark time, illuminated only by the radiance of Echavarren’s poetic language. This, in a country now condemned to a double disintegration that transcends and signifies, and towards which most nations are beginning to turn a deaf ear, whether by aligning with the enemy or by prioritizing their own interests, beyond the urgency of maintaining global balance.

The poetic voice denounces, asserting itself against a reality that surpasses it, that is, against a hyperreality where war, as Hannah Arendt indicated, is still the ultimate arbiter. This calls into question the effectiveness of other forms of arbitration and negotiation which, in the case of this conflict, were doomed to fail. As Echavarren clarifies in the preface to the poem, according to the Memorandum on Security Assurances signed in Budapest in 1994, “Ukraine was guarantee to maintain its territorial integrity, with Moscow as one of the cosigners” in exchange for eliminating nuclear weapons from its territory. Another farce, indeed, adding to the void promises of an autocracy determined to invade or destroy all those nations that refuse to align with its project of reconstruction of the former Soviet bloc.

Narrative and Narratives

A portion of Echavarren’s recent narrative production, gathered in Archipiélago. Tres novelas (2017), returns to the more personal exploration of the body and desire from a homoerotic perspective, in three narratives that unfold on an archipelago both geographical and literary. “El pintor de Creta”, “El surfista de Bali”, and “El fotógrafo de Manhattan” establish, echoing Sarduy, a series of “conjunctions and disjunctions” with previous works such as Ave Roc (1994) and Arte andrógino (1997).

In the first narrative, it is the materialization of a “plurivocal lifestyle, based on a play of differences,” as we read in Arte andrógino, what is achieved through poetic descriptions that redeem classical antiquity by correcting the absence of a multiple vision over its past. A vision magnified here by the precision of a language that recovers the excesses of history itself upon Cretan culture. The painter’s petite histoire becomes then intertwined with that of the island, seen as “a field of ruins” after centuries of invasions. Among the ruins, writing recovers The Priest of the Lilies, a fresco still discernible amidst the remains of the palace of Knossos, that represents “a teenager with long hair, a feathered cap, an incredibly narrow waist” whose beauty bewitches the protagonist, leading him to seek it in his sexual conquests on and off the island.

“El surfista de Bali” incorporates the invasion of the body from within into the androgynous gaze, because of the illness that settles in and attacks it. However, the protagonist does not dwell on victimization; he rises above it to counterattack it through enjoyment and adventure. As Emil Cioran proposes, “it is not the eruption of an undefined evil that reminds us of our fragility.” It is precisely from illness that the surfer draws strength to glide over his weakness, as if the waves were calling him in the roar of the seas, visited alone or with his partner, who later becomes a victim of contemporary hatred. The vision of a young transgender person in the hostel where the protagonist stays upon arriving in Bali, the encounter with the Dutchman who will be his husband, the jihadist terrorism exploding in a nightclub where he had been two weeks before, the racism of a friend of his partner delighted to have moved to a neighborhood in Amsterdam where “everyone is white,” weave the network of meanings extending over the work and knotting the author’s past and present.

“El fotógrafo de Manhattan” articulates these temporal spaces through autofiction, recounting Echavarren’s memories of the years when he intensely lived the city. The fusion of themes, styles, and fashions with literary, artistic, and film projects generates a narrative corpus where New York is observed through the prism of a perpetually ambiguous youth, inhabiting a “hybrid (that) seemed to be the center of the world,” as perceived by the narrator of Ave Roc. This fascination with the androgyny of the body and the dress of a group of rockers, turned improvised actors for the film Atlantic Casino, is revisited here. Such overlapping of lived and fictionalized hyperrealities, when extracted from personal chronology, gains significance in fiction as, to quote David Hume, “ideas (that) always represent the objects or impressions from which they derive and can never, without fiction, represent others or be applied to others.” Consequently, they manage to coexist simultaneously in the author’s and the photographer’s temporality, generating a dual perspective on the writer’s work and life.

Testimony and Testimonies

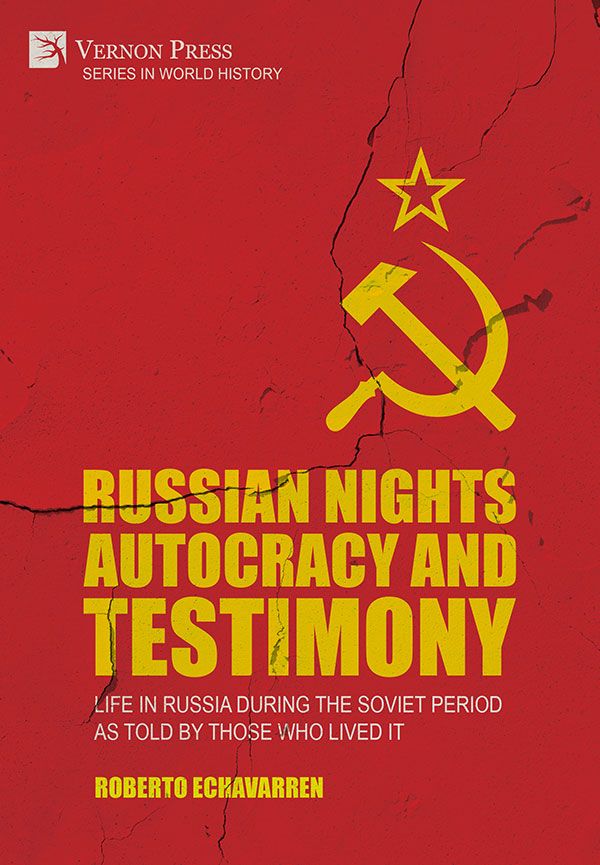

It is in the works about Russia where that dual perspective becomes globalized through compiled testimony and testimonies. Among them, Russian Nights (2023) offers a powerful account of life under the control of Lenin and Stalin, extending the analysis to the post-Perestroika era determined by Putin’s authoritarian government. Here, the transformation of the nation from the Tsarist empire to the socialist state is traced, combining historical context with first-hand testimonies of those who suffered repression and torture, to provide a broad view of power and submission. All this frames the chronicles of voices never heard before, revealing a Russia marked by the destinies of countless lives sacrificed or ruined by the communist regime. However, quoting Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, “(it would have been) difficult to design a path out of communism worse than the one that has been followed,” in view of the ominous turn of the country towards military autocracy in the 21st century, now threatening global stability.

With these testimonies, Roberto Echavarren brings to the forefront the voices that were previously silenced, shedding light on the experiences of the victims, while examining one of the most traumatic chapters in Russian history. A chapter which is part of a broader present, as he indicates in the conclusion. This continuum is characterized, following Étienne Balibar’s classification, by a global division into “zones of life and zones of death,” due to extreme violence. A division exacerbated today by polarization, and with no room for agreement and compromise. The 21st century, since the terrorist attacks of September 11, has been marked by confrontation and destruction, and Russian Nights is a lucid reminder that the worst is yet to come.