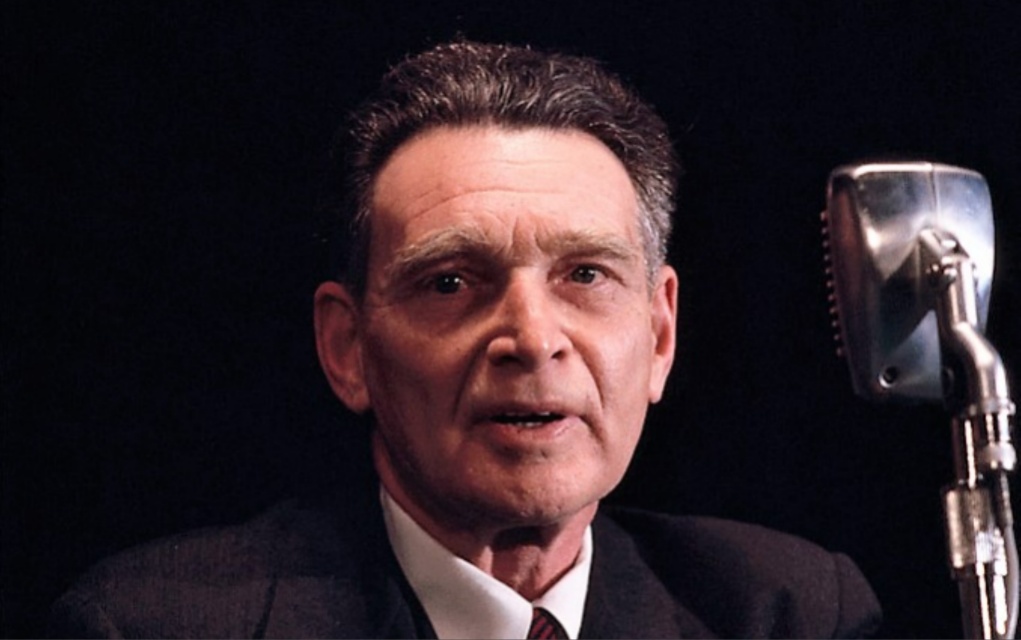

Oscar Lewis (1914-1970) is one of the most relevant personalities of sociocultural anthropology in the mid-twentieth century due to his work’s theoretical and methodological impact on the discussions about the phenomenon of poverty. Although he received his training in American academies, it was his long ethnographic stays in rural and urban settlements in countries such as the United States, Mexico, Spain, India, Puerto Rico, and Cuba that led to a reorientation of his epistemological positions towards more holistic and interdisciplinary sociocultural anthropology. A reorientation whose main focus was the inconsistencies, irregularities, and instabilities of the internal dynamics of cultural change within social systems.

To this extent, his disciplinary praxis is difficult to pigeonhole as a continuation of any of the hegemonic schools of anthropological thought, having taken, readapted, and mixed the central concerns of North American cultural anthropology, then oriented to the identification of “patterns of culture” and psychological aspects of personality,[1] under the impulse of the so-called “school of culture and personality.” It also assumed the main orientations of the British school of social anthropology, more interested in the functional aspect of organization and structure of social relations in the human groups under study.

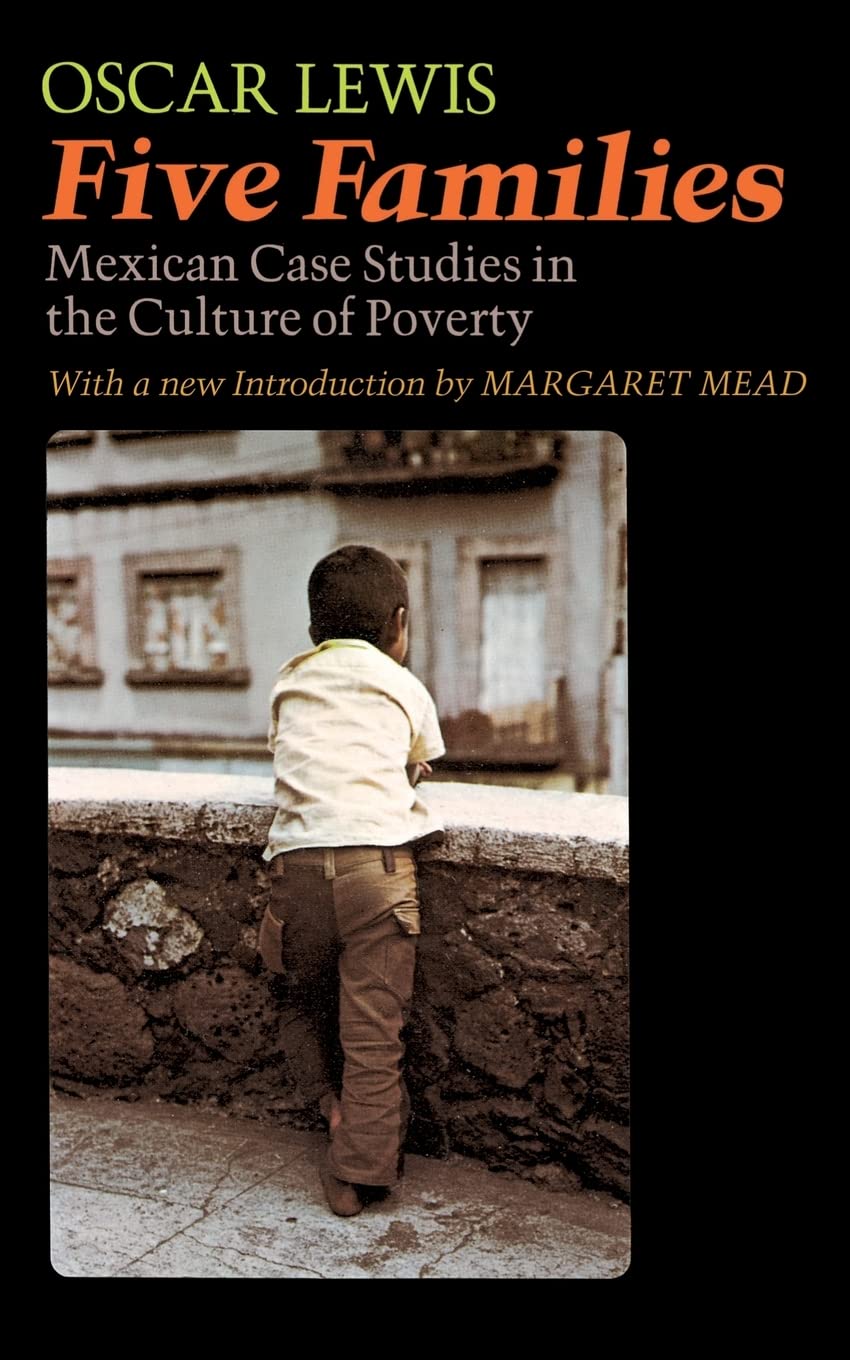

Five Families; Mexican Case Studies in the Culture of Poverty (1959) and The Children of Sanchez (1961) are, probably, his best-known books and where the hard core of his ethnographic theory and anthropological concepts, built while in Mexico, were exhibited. These include his original formulation of the “culture of poverty,”[2] as well as the methods of “multiple autobiographies”[3] and “reinvestigation” or re-study of the same community. The complementarity between each offered an alternative form to the genealogical method for what he called the “intensive studies of a single extended family.”[4]

The choice of oral life histories as the preferred scriptural form for the display of the final results of fieldwork has remained in a realm of methodological criticism that often disregards the extensive ethnographic work behind it; one complemented, moreover, by other methods, such as the recording of “a common day.” The latter, among other positions, led to his books being labeled as works of “fiction” or “great literature”[5] Labels as reproduced as they are questionable in the light of the development of contemporary ethnographic theory, starting with the discussions of postmodern anthropology on the scriptural forms of ethnographic authority.

On the other hand, the tense relations and polemics resulting from the clash of interests with state nationalisms constituted a permanent problem that affected the publication of his books wherever he stayed. In Mexico, a precedent of conflict was created between the representations of revolutionary state nationalism, with developmentalist and “modernist” aspirations, and the representations generated ethnographically by Oscar Lewis about the universe of poverty and the impact of revolutionary policies. Henceforth, the climax of double accusations—as an alleged “agent of colonialism and the CIA” and “opinionated communist” —turned his books into a political issue, which led to repeated attempts at expulsion from that country and coercion in others, such as Spain, in 1949.

Regarding the latter, it was in Spain where he tried to initiate, probably, his first project with comparative purposes between the Spanish culture and its manifestations observed in the Mexican town of Tepoztlán. The studies on the latter started in 1943 his first anthropological project on large ethnographic scales. It was precisely these expansions of scales, going from regional to transnational accompanied by a certain more or less radical empiricism, which led him to fix his interest in Cuba, which he made explicit since the study on the “culture of poverty” in Puerto Rico.

Although this interest was oriented to observe the variations of the “culture of poverty” in different national contexts, Oscar Lewis was motivated by a greater academic interest in the Caribbean archipelago. Initially, he was interested in answering ethnographically how the “culture of poverty” would be constructed in countries with socialist systems and what made Cuba different from other socialisms. Beyond ethnographically recording life under socialism, the main interest was to study the internal dynamics of social and cultural change, linked to the phenomenon of revolutions[6] in states that aspired to build national, developmental, and modern systems. In particular, he wondered whether the Cuban Revolution might be far from being taken as a “uniform experience.”[7]

His speculative hypothesis tried to verify whether the subjective conditions associated with the “culture of poverty” could be diminished in Cuba, given the assumption that socialist revolutions would abolish some of its basic characteristics, even if they did not eliminate poverty. Before the Cuban case, Oscar Lewis had considered the “culture of poverty” as an exclusive manifestation of “capitalist societies stratified into classes and with a high level of individualization.” Meanwhile, Cuba would offer the possibility of studying the impact of an ongoing and rapidly changing revolution from the sphere of family life; considered one of the main vehicles for the transmission of “new social and political values” as well as one of “the most important allies” of the revolutionary State.

As antecedents of this project are his three visits to Cuba. The first, in 1946, when, still under the capitalist system, he was interested in studying the material conditions of life under poverty in a rural locality of the Melena del Sur municipality and, especially, in the Las Yaguas settlement, located in the Luyanó municipality of Havana. The latter was one of the so-called “slums” “poor neighborhoods” or “shantytowns”. Upon his return in 1961, he noted high local levels of institutional integration but without much change in the material conditions of life. Las Yaguas was then in the process of being dismantled and moved to the new housing complexes, called Buena Ventura, better known popularly as Las Yaguas Made of Masonry. It was during his third trip, which took place in 1968, when the possibility of carrying out an extensive ethnography was institutionally established, under the invitation and auspices of the Cuban Book Institute, the Cuban Academy of Sciences, and the approval of the Government.

Thus, the so-called Cuba Project began on February 20, 1969, with a planned duration of three years.[8] In personal terms, this was Oscar Lewis’ last stay in the field, towards the end of his life, when his proposals had reached a certain level of conceptual and methodological stabilization. As a result, rather than describing in binary terms the “achievements” and “failures” of the Revolution, the aim was to provide original knowledge about the internal dynamics of social and cultural change in Cuba. However, state authorities suddenly canceled his project on June 25, 1970, and Oscar Lewis was shortly singled out as an example of “political, economic, social and cultural espionage” by the United States. The only existing material for consultation of the total confiscated is the trilogy of volumes Cuatro hombres, Cuatro mujeres, and Neighbors,[9] which amounts to a total of 1562 pages in English, 1189 of which have been translated into Spanish, as well as the book The People of Buena Ventura: Relocation of Slum Dwellers in Postrevolutionary Cuba (Butterworth, 1980). Oscar Lewis died shortly after the cancellation, in December 1970, as a result of heart failure.

Controversies regarding the abrupt closure of the project have been the subject of analysis by other researchers, such as Lillian Guerra. A less explored area is what repercussions the formulation of this project and its termination may have had on state perceptions and the national status of sociocultural anthropology, in contrast to the ethnological tradition. Nor has the coincidence of this—exceptional?—event been related to the abrupt closure of the National Institute of Ethnology and Folklore (INEF) in 1969. In the case of the Cuba Project, Ruth Lewis analyzed this action as part of a “general crisis of intellectuals” and the espionage climate of the Cold War, which seemed to justify mutual suspicions about the work and social role of foreign intellectuals and academics.

Apart from these issues, Oscar Lewis’s anthropology touched on several topics of national interest, among them, the transformation or social change between “poverty” and the “popular”; an area that was a fundamental object of official rhetoric and nationalist constructions around the newly reconstituted categories of “popular” sectors or the “collectivity.” Under these national constructions, discourses were expanded that considered phenomena such as poverty and racism as “eradicated.”[10] The latter is based exclusively on the “elimination” of institutional racism through the undermining of its structural foundations.[11]

While the 1960s had been characterized by a greater openness to external intellectual discussions and influences motivated by the visits of social scientists and intellectuals, who produced books of their direct observations in the country, such as Wright Mills (1960) and Jean-Paul Sartre (1961), the 1970s inaugurated the beginning of a context of radicalization. Often referred to in the artistic-cultural sphere as the gray quinquennium, Cuban institutions during this period were redefined in the sense of the terms of the socialist project and the collective interests of the so-called “culture of the people.” A process in which the terms of the ideological sphere took precedence, producing a shift towards the “patterns of the Soviet cultural model.”[12] National anthropology did not escape from this trend, where the influence of the so-called Soviet school of theoretical ethnography was evident. As a result of all these circumstances, between the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s, there was a change of orientation or turn in the national discipline.

To this day, sociocultural anthropology is a discipline that still does not enjoy “full social recognition” in Cuba.[13] In addition, the influence of Oscar Lewis has been little systematized and valued according to its impact, which, however, has been recognized by personalities such as the ethnologist Miguel Barnet, who mentions the anthropologist’s contributions to the method of life histories and the autobiographical perspective, developed by him in his research, as in Biography of a Runaway Slave.[14] While for anthropologist Pablo Rodríguez, Oscar Lewis offered an elementary frame of reference for his studies on poverty and marginality in Cuba.[15]

The latent issue here is to what extent, how, and how much of that influence has remained embedded in the disciplinary practice and impacted on the state perception and current status of sociocultural anthropology in the country. Thus, this essay outlines some of the interests of a broader line of research on the development of national anthropologies, where one of its lines is the development of an analysis of the contributions of Oscar Lewis and the development of the Cuba Project, in the historical context of the turn of the discipline and the construction of a sociocultural anthropology, in the future.

The usefulness of this knowledge would go beyond the geographical framework of Cuba given the significant absence of an intellectual biography of Oscar Lewis in which his biographical data in Spanish are systematized and analyzed, especially, the influence of his teachers of the North American school—such as Ruth Benedict, Ralph Linton, Abram Kardiner, among others—and their contrast with the directions taken by his anthropology. On the other hand, in countries like Mexico, except for authors such as Eduardo Nivón, and Ana Rosas Mantecón; Jorge Aceves, and Claudio Lomnitz,[16] the absence of reviews of his work is paradoxical, when he is considered one of the most influential foreign scholars and precursor of urban studies. Nor have his contributions to the method of “multiple autobiographies” been discussed in contrast to the life narratives, elaborated without interweaving, by other anthropologists such as Ricardo Pozas. In other words, it is about covering one of the areas and objects more or less relegated in contemporary anthropological theory and historically made illegitimate in the Cuban discipline.

Notes:

[1] Ruth Benedict: El hombre y la cultura, Editorial Sudamericana, Buenos Aires, 1967 [1934].

[2] The culture or subculture of poverty was conceptualized as a unit of observation and recording of the material and spiritual conditions of marginalization, with more or less fixed cultural expressions that are transmitted through generations and offer greater resistance to change.

[3] The “multiple autobiographies” or “Rashomon-style technique” consists of seeing the family through the eyes of each of its members through their life stories, told in their own words. An approach that Oscar Lewis advocated for allowing a direct, human, and emotional exploration with the people, which was rarely conveyed in the “formal jargon of anthropological monographs.”

[4] Oscar Lewis: Antropología de la pobreza. Cinco familias Fondo de Cultura Económica, México City, 1975 [1959]; Los hijos de Sánchez: Autobiografía de una familia mexicana. Joaquín Mortiz, Mexico City, 1978 [1961].

[5] Ricardo Pozas: “La pobre antropología de Oscar Lewis”, Revista de la Universidad de México, 1961.

[6] It should be pointed out that Oscar Lewis’ interest in the study of revolutions originated in Mexico. His interest in the Cuban revolution was declared in that country, in the study with Pedro Martínez.

[7] Oscar Lewis and Susan R. Rigdon: Viviendo la Revolución: Cuatro Hombres. Una historia oral de Cuba contemporánea, Joaquín Mortiz, México D. F., 1980 [1977]; Vivencias durante la Revolución cubana: Cuatro Mujeres. Una historia oral de la Cuba contemporánea, Plaza&Janes Editores, Barcelona, 1980 [1977].

[8] Lillian Guerra: “Former Slum Dwellers, the Communist Youth, and the Lewis Project in Cuba, 1969-1971,” Cuban Studies, vol. 43, pp. 67-89, 2015.

[9] English titles are retained to highlight the absence of available Spanish translations of the original books.

[10] José Luis Rodríguez García and George Carrizaro Moreno: Erradicación de la pobreza en Cuba, Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, Havana, 1987.

[11] VV. AA.: Las relaciones raciales en Cuba: estudios contemporáneos, Fundación Fernando Ortiz, Havana, 2010.

[12] Sergio Valdés Paz: La evolución del poder en la Revolución cubana. Tomo I, Roxa Lexemburgo Stifung, Mexico City, 2017.

[13] Niurka Núñez González: “Introducción. Hacia una historia otra de la antropología en Cuba”, in Niurka Núñez González (coord.), Antropología Sociocultural en Cuba. Revisiones históricas e historiográficas. Tomo I, Cuban Institute of Cultural Research Juan Marinello, Havana, 2020, p. 23.

[14] Miguel Barnet: “‘Neither an epigone of Oscar Lewis nor of Truman Capote.’ Yanko González, interview to Miguel Barnet”, Revista Austral de Ciencias Sociales 13, pp. 93-110.

[15] Pablo Rodríguez Ruiz: Los marginales de Alturas de Mirador. Un estudio de caso, Fernando Ortiz Foundation, Havana, 2011.

[16] Eduardo Nivón and Ana Rosas Mantecón: “Oscar Lewis revisitado”, Alteridades, vol. 4, no. 7, 1994, pp. 5-7; Claudio Lomnitz: “Prólogo”, in Oscar Lewis, Los Hijos de Sánchez. Autobiografía de una familia mexicana/Una muerte en la familia Sánchez, Fondo de Cultura Económica, Mexico City, 2011, pp. 7-21; Jorge Aceves Lozano: “Oscar Lewis y su aporte a las historias de vida,” Alteridades, 4 (7), pp. 27-33, 1994.