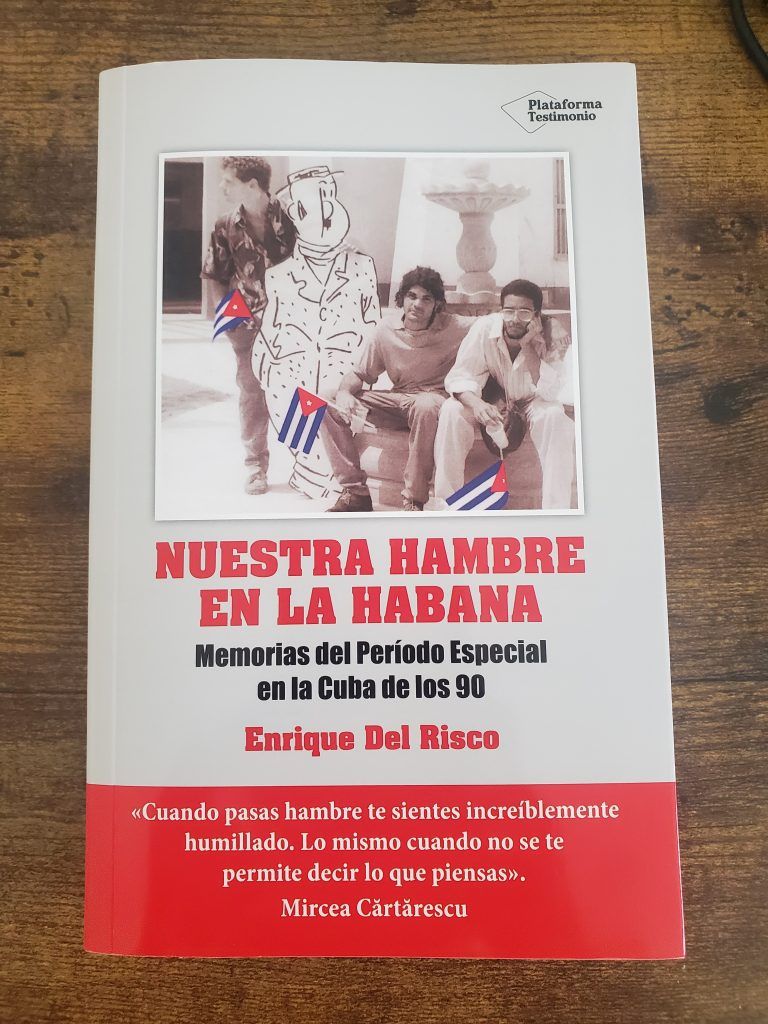

When we talk about food memory we might think of the memory of a family meal, of flavors and smells that symbolize places, people and moments. But food memory represents much more than our immediate evocations. It can explain the evolution of a country, the various behaviors of its society, even language, collective dispositions and aversions. This is precisely the reflection that writer Enrique Del Risco brings us in his latest title Nuestra hambre en La Habana (Plataforma Editorial, 2022). Del Risco places his narrative between the years immediately after the fall of the Berlin Wall and his definitive departure from the country in 1995. This time frame would seem quite tight for a memoir, if it were not taken into account that it encapsulates, to a great extent, the period of major rearrangements, improvisations and resistances, euphemistically known as the Special Period in Times of Peace. Although the title of Nuestra hambre… forebodes an uncomfortable reading, Del Risco combines history, literature and humor to temper what would otherwise be sad and embarrassingly nostalgic.

Although Nuestra hambre… is a personal testimony, it can be also considered, with a few exceptions, a collective memory, a chronicle of the experiences shared by the author and the rest of the millions of Cubans. Cubans who, like him, considered the Chinese bicycles given by the Government as their most precious belongings; who entered movie theaters to get excited when scenes of banquets or sex appeared, the two greatest lusts of that time; who considered themselves fortunate when they could unexpectedly buy some food, which they shared among close relatives and hid from the rest. The book gets it right then in the possessive pronoun with which its title begins, because anyone who had lived “That time,” as its author refers to the period, recognizes in its words such familiar passages as turning down the volume of the TV set during the speeches of “You-Know-Who.” This is a personal memory that I would like to interject here: the habit of delaying the ritual of the meal until the transmission ended and whatever soap opera being broadcasted at time began. Seeking a more pleasant environment than the combative speech to ingest our food is another example of the food memory shared by several generations.

We should place Nuestra hambre… in a more accurate description. Rather than a testimonial product of food memory, it is a product of food memory during crisis. What guides the narrative is not abundance, or even a meager diet, but the evident lack of food. Without being a nutritionist, the experience of having lived through the cruelest period of the nineties, allows the author to affirm that: “One of the first things that hunger helps you to know better is your own body […] With hunger you discover how your body works without the interference of nutrients. An empty stomach is like a laboratory in aseptic and controlled conditions so that experiments can achieve reliable results and you can see for yourself the ability of each type of food to satiate you, the exact duration of its effects.”

But there is another element glaringly missing in the narrative, as a unit, as a status quo, as a pact and justification for the breakdown of structures and norms. As the author states: “those moments of absolute moral debacle, in which survival governs all your actions, ethics depends only on what you decide to forbid yourself.” Ethics then turned out to be an exercise of restriction among restrictions, where it was difficult to find common sense outside of deprivation. For Del Risco, then came the moment of barbarism when Cubans assumed the precarious condition of survivors: “It came when people lost all hope of building a better society. Or a worse one, but at least something new. When beauty became, more than superfluous, offensive. When the desire for survival directed our every act and we saw in the slightest deviation from that goal a threat, a mockery. Barbarism came when we abandoned any expectation of building or repairing anything.”

Just as the crisis went beyond the frontiers of the economy, hunger went beyond those of food. That is why we can find in the text Hunger with a capital letter, assimilated to major constructs such as History or Humanity. The Hunger was a period marked by so many absences that the author summarizes the illusions of his generation in the simplest way: “That was more or less our idea of happiness during the Hunger: a night with food and electricity.” Beyond material shortages, Del Risco also narrates the disillusions and hardships of his closest sector: cultural censorship that bans exhibitions or seizes uncomfortable publications; surveillance by colleagues, neighbors and supervising agents; the resignation around the 1993 parliamentary elections; homemade alcohol as a form of alienation from reality; leaving the country as a more decisive way of dealing with that reality.

For Del Risco, both physical hunger and symbolic Hunger have been hidden from us; Cubans lack pedigree in the face of the great tragedies in history: “Our hunger was a hunger with low self-esteem. It still is. Many people still do not dare to call it by its name.” In the face of recognized genocides “we must step back, humbly, recognizing that our hungry condition did not reach such extremes.” In the face of this absence, marked by academics and militant intellectuals, pilgrims of the Cuban cause who relativize or romanticize the precariousness of the 1990s on the island, Nuestra hambre… comes to vindicate the feelings of Cubans, their experiences, and their memories.

In the epilogue, Del Risco also speaks to Cubans without border distinctions, puts a mirror in front of us, invites us to confront ourselves with our immediate past, to express a mea culpa as part of the barbarism we lived then, starting with his own person, an essential gesture necessary for national reconciliation. The inventory of exercises to dodge hunger and its ramifications that Del Risco provides, in short, is a true sample of the Cuban social imaginary, an indispensable part of what we are in the present, but, above all, a veiled invitation to shake off despair and immobility, to build a new food memory where hunger is not the protagonist of our lives.