In this exclusive interview with Ted Henken, New York graphic artist, blogger, and one-time habanera Anna Veltfort shares the contents of her “Cuban Cold War closet,” revealing long-held secrets from the decade she and her family spent in Cuba during the Revolution’s honeymoon years. For her, and for many other young gay artists of her generation, these were both tough and luminous years filled with illusions, idealism, and unforgettable events, both exhilarating and terrifying.

Brought to Cuba by her Communist parents as a 16-year-old in early 1962, Veltfort attended high school and college alongside her Cuban classmates, eventually graduating in Art History from the University of Havana in 1972. As she came of age in this heady and politically polarized environment, she enthusiastically joined in to build a better world as a proud revolutionary, doing voluntary agricultural labor around Havana and conducting social research among the peasants of the Sierra Maestra Mountains.

At the same time, she quickly perceived that daily life for her ordinary Cuban friends bore little resemblance to the privileged circumstances her family enjoyed as “foreign technicians.” Veltfort also endured harrowing first-hand experiences of gay paranoia and repression as she explored and defined her own sexual identity as a lesbian during the time of cruel homophobic purges that swept through Cuban society.

At the most basic level, her book Goodbye, My Havana: The Life and Times of a Gringa in Revolutionary Cuba (Redwood Press, 2019; Verbum, 2017) is a coming of age memoir. But it is also the work of a very talented graphic artist. Perhaps most importantly, it is a first-hand testimonial and admonition about the perverse reality lurking beneath an often-romanticized Revolution.

For me, as someone who has studied Cuban history and society, what’s most fascinating about your book is that it tells a rare heterodox story about the Cuban Revolution. It is the story of the many different kinds of people, including yourself, who once thought of themselves as revolutionaries, but found over time that they were considered apostates. We often hear criticisms in the United States of the Revolution that come from a place of imperial arrogance or woeful ignorance, but what this book reveals are the much more complex and diverse reactions of Cubans themselves to the Revolution from within. Your memoir is a tale of someone who was initially bewitched by the Revolution, who embraced the promises and dreams of a new generation who were building a new society. At the same time, it is a tale of bitter heartbreak, an intensely personal reflection of someone who came to know only too well the high price that was paid for those dreams, very often without a choice.

How did it occur to you to approach telling this story not only as a personal memoir but also as a graphic one? And how was that related to your blog, “El Archivo de Connie”? You were a blogger for most of the decade that you were writing this book (2007-2018) and so I’m curious about the origins of Goodbye, My Havana.

Anna Veltfort: When I left Cuba in 1972, I brought with me a huge treasure trove of cultural artifacts, books, albums, posters, magazines, and political screeds published by the government during the times of persecution in the 1960s. These were all very important and valuable to me as they helped me keep a grip on my Cuban identity. As a privileged foreigner, I was able to leave Cuba on a cargo ship and bring with all these materials with me in large boxes. When I got to New York, I was poor but I managed to make a life here and get survival jobs. What happened to all these boxes of Cuban ephemera? What was I going to do with these memories in physical form? They went into drawers and closets and were not seen again for decades. There was no way that I could relate them to my new life in the United States. I was now on another planet. They sat in my closet for all those years.

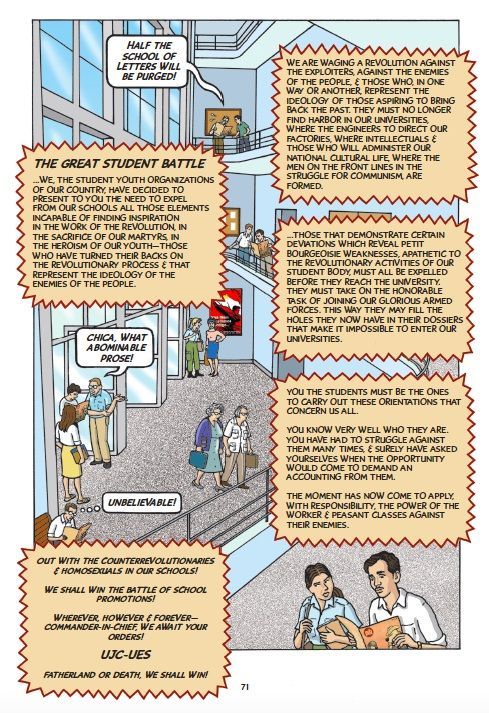

Then, in 2007 the Cuban state decided that they were going to whitewash all that had happened in the 60s and 70s, the history of the purges in the cultural world, in theater, the schools, the purging of writers, visual artists, musicians, and dancers. All these cultural entities were combed for homosexuals. Other supposed “deviants” like Jehovah’s Witnesses were considered suspect as well, but the brunt of it was against homosexuals and “counterrevolutionaries.” Both came to be deemed the same thing. Three bureaucrats, Luis Pavón, Papito Serguera, and Armando Quesada, were the officials who directed these purges. Of course, they weren’t the ones ultimately responsible. We know who ran the country with an iron fist. People accused of being gay were cited to appear at meetings and told that they were being expelled because they were the scum of society and didn’t deserve to be part of Cuban culture any longer. They were often publicly humiliated and then sent to work in a factory or to cut cane.

I found out about this whitewashing along with other people who followed the Cuban press. By 2007 we had entered the new digital era. Blogs were beginning to appear and people had started to use email to communicate. So now when these people were brought out on national television the government tried to present them as rehabilitated heroes of the cultural past. Cubans in the diaspora, in Miami, Spain, and Mexico, even the few Cubans in Cuba who had access to email, urgently discussed this. “How dare they bring out Quesada, Serguera and Pavón? Is this the beginning of a new era of repression?”

This collective digital campaign to prevent the Cuban government from sanitizing, or simply erasing so much of this thorny history, came to be called “La guerrita de los emails” (The little email war). I too was on email then and reading this new thing called the Internet. Collective protest had never happened before. I got just as incensed as the others and decided to join the fray by creating my own blog. I went to NYU and took a night course on how to make a website. You had to learn HTML then, you had to learn how to code.

I called my blog “El Archivo de Connie” (Connie’s Archive) because it was a showcase of my personal archives and my friends in Cuba knew me by my nickname Connie. I felt I couldn’t enter into discussions about these things, because who was I? I had only been a university art history student in Havana and I hadn’t been there for decades. Yet I had all of these materials that had been sitting for 30 years in my closet, including magazines and government pamphlets exhorting students to go out and terrorize homosexuals. Most likely no one else had these materials outside of Cuba and in Cuba, copies had probably rotted long ago because of the humidity, or were hidden in the basement of La Biblioteca Nacional for no one to see.

I first posted screeds published in official newspapers and magazines, aimed at university students, which denounced the presence of homosexuals who must be hunted and rooted out. I had no idea I would be posting on the blog for 10 years. Creating this digital archive brought back all the memories and feelings attached to them. Then in 2008 what happened? The financial crisis. I was suddenly unemployed. I had time on my hands.

And so, my partner, Stacy, said: “Well, at least I’ve got a job, I can pay the bills. Here is your opportunity to finally write the book that you always wanted to do about your life in Cuba.” I thought, “OK, how can I possibly do that? I’m not a writer, I’m a graphic artist, I illustrate educational books. Maybe I can do it as a graphic novel?” I decided to use the archive material, mine my memories, use the photographs that I had from the past and tell my story through texts and drawings. It took over 10 years until the book came out in English last October in 2019. Almost the same amount of time I had lived in Cuba.

How do other Americans react when they discover you grew up in Communist Cuba in the 1960s?

When people have asked me: “Oh, you lived in Cuba! What was that like?” It has been impossible to answer, to talk about that other world. I pretty much avoided the question and would change the subject as soon as politely possible. But I did want to explain to my closest friends and family, my partner Stacy and then our daughter Sophia. After moving to New York after Cuba, I became an illustrator and a graphic artist, but not a writer. So, it took me a long time to figure it out. There were too many things that were not sayable. They had to be felt, be seen, and experienced.

I tried to cross that barrier by visual means. My big comic book. I didn’t aspire to writing something very literary and complex. I wanted a simple straight forward text to accompany my drawings, which I researched extensively. I asked friends who still live in Havana to take photos which I used to help me reconstruct that world from so long ago. I wanted it to be as authentic as possible. Not only for the sake of authenticity but because despite everything that’s happened and how much it has deteriorated over time, Havana is a heartbreakingly beautiful city by the sea, a lovely, bewitching place. I wanted very much to show that in my book.

When working on the memoir so many years later between 2007 and 2017, how did you deal with the challenge of being true to the person you were during that decade, between 1962 and 1972, and not having the woman you are now, forty years later, edit and try to make yourself look… maybe match, let’s say, your current beliefs or opinions or perspectives.

So many books have been written about the Cuban Revolution, generally very, very anti- or very, very pro-, and I didn’t think that I was either qualified or interested in going into that fray. But what I did have was that experience. I hoped to simply paint a portrait of Cuba, of that time, seen through the eyes of a young woman who happened to go there for reasons of family, came out as a lesbian, and lived this revolutionary experience.

I decided that I had to go into 100% immersion mode by working from 10 o’clock at night to about 4 o’clock in the morning every day. No distractions. I took out all the photo albums that I had, all the letters, all the music, all the Bola de Nieve albums, all those things I had been able to bring with me. Every night I listened, I drew, and I wrote. And I think that I was able to put myself back into that place emotionally and into who I had been then.

Well, since we’re talking about a graphic novel, there’s much more going on than appears in the text. So, I’m curious about how you produce the images and illustrations based on the source material. You already described how you had collected the source material and kept it locked away in a closet for 35 years, so now let’s see some of that alongside the final product published in the book. In other words, let’s take a little trip into the mind of an illustrator.

So, my question is: How does an illustrator turn sketches into a graphic memoir starting with some of the original illustrations that you did in the 60s in Cuba that you still have in your possession, some of which –if I understand correctly– you actually sent by letter to your sister in the United States. She saved these sketches and 40 years later you used them as a basis to recall the images reproduced in the book.

Yes, this is the reason I was able to show so many details of my little one-room apartment in Nuevo Vedado, during my last years in Cuba. I had wanted to show my little sister Nikki, who had returned to the States in 1968 with the rest of the family, what my life was like now. So, I painted these four watercolor sketches of my room and mailed them to her. When she died, my mother kept them, and gave them to me years later.

Imagine writing a letter to your sibling in another country, and instead of describing your room you draw a picture, four pictures of your room and then you save that for 40 years. To me it was just amazing that you had these. And then, if we look at these strategically alongside page 158 in the book, you can see the background is the apartment that you had. I assume that for you this was a great oasis where you could be yourself, for the first time you lived by yourself, you could have your girlfriend over, your friends over, have parties. If you look closely, you can see the same posters, the same sofa, the guitar, the decorations, right? And that allowed you to then, to capture that, right?

Imagine writing a letter to your sibling in another country, and instead of describing your room you draw a picture, four pictures of your room and then you save that for 40 years. To me it was just amazing that you had these. And then, if we look at these strategically alongside page 158 in the book, you can see the background is the apartment that you had. I assume that for you this was a great oasis where you could be yourself, for the first time you lived by yourself, you could have your girlfriend over, your friends over, have parties. If you look closely, you can see the same posters, the same sofa, the guitar, the decorations, right? And that allowed you to then, to capture that, right?

Exactly, yes!

There’s another good example of your doing this in the book when Fidel Castro makes a surprise visit to the University and you actually speak to him briefly one-on-one. Can you describe that scene for us and how you converted the material into illustrations for your book?

Yes, one day we were waiting outside our school to be picked up by trucks to be taken to yet another agricultural work week, and who comes by in a jeep but Fidel Castro and his entourage. In those years, he used to do that a lot. He liked showing up unexpectedly in different parts of the University to talk with the students. But he wasn’t likely to come to our school because Letras was known as the school full of perverts. He intended to go to another school but as he was driving by we all started shrieking, “Fidel, Fidel, come and talk to us!” and so he did.

He stopped and stepped out of his jeep. You can see here, I used these photographs taken by press photographers as references. I had a friend in the school of Journalism who gave me some of these photographs then and here they are. I made full use of them in the book. That’s me sitting at Fidel’s feet. Right before that I had a conversation with him. He gave me a five-minute lecture on the new way that they were going to be planting pineapple in Cuba. And then he moved on to the stage to exhort us to go out and work in agriculture because we were going to be better revolutionaries for it.

The worst thing that ever happened to me in Cuba occurred a couple of weeks after Fidel had come to the Escuela de Letras. One day, I decided to go to the movies with my then girlfriend Marta Eugenia. We went to the Malecón to chat after seeing this movie called Morgan!, a British film. Soon, a couple of guys drove up and started hurling insults at us after we refused to get in the car with them. They got out of their car and beat us up and then took off. Moments later the police arrived and took us away to a police station where we were miraculously converted from being the victims of an assault into perpetrators who had behaved in an immoral and indecent manner on the Malecón.

Wrongly accused, we were tried in two parallel trials one by the city and one by the university. We received multiple summonses in the mail, a real nightmare for about a year and a half. The winds of persecution rose and then died down. And after a time, they stopped. These panels show the interrogations that I had to go through in the university trial. Finally, the whole thing dissipated and when I moved from one home to another, when my parents left, and I moved to Nuevo Vedado, I stopped getting summonses in the mail, they started leaving Marta Eugenia alone at the University, and we survived (or so we thought). Some students in the middle of all that were expelled. They went through their own very, very hard times.

So, who is Anna Veltfort and how did she wind up in Cuba in the first place?

I lived the first seven years of my life in Germany where I was born, and emigrated to the United States in 1952 with my single mother. We were quite poor, and arrived with two suitcases and a box of books. I was terrified I was never going to learn English. I lived here during the next nine years of my life, learning to become an American.

At the age of 16, for the next 10 years, I lived in Cuba, where I went to high school and college. So, I’m a mix of three different cultures and an immigrant three times over. I felt that especially when I finally returned to the States and settled here in 1972. People have asked me from time to time, “when you lived in Cuba and lived through so many hardships and then visited the States, why did you go back?” For me the answer was obvious: I had a life there, I had my friends there, I was in a relationship that meant a lot to me, and I was in school. I was studying Art History at the University of Havana, tuition free. This was not what Americans might expect in a revolution but that was my life.

I didn’t get along with my parents, so living with them would have been the last option. It felt completely natural for me to return to Cuba. It wasn’t as if the United States was the anchor of my life then. It was just one of the places that I had passed through. Moving back from Cuba when I was 27 was especially hard. Everything that I had learned in my 20s, while coming of age, all happened to me in Cuba. I had to learn from scratch how people interact here, to learn to understand the body language of Americans. The cultural adaptation was very hard for me.

Why did I move to Cuba when I was 16? After emigrating to the US when I was seven years old with my mother, we had made our way to California where my mother married an American named Ted Veltfort. They fell in love, and got married very quickly. He turned out to be an American communist, something that my mother knew nothing about. She was just an average middle-class German, traumatized by WWII, who knew nothing about American politics and certainly nothing about Communism. He had been a communist for years.

Ted had fought in the Spanish Civil War against Franco, the first battle against fascism in Europe shortly before WWII. He was very involved in leftist politics in California in the 1950s, and was persecuted by the American government for being a communist and for having fought in Spain. Suddenly, I moved from the world of a little German immigrant and into this very paranoid world of a community of people persecuted for being leftists. That brought a lot of problems and complications along the way for me and my family.

Then, in 1959, what happened? The Cuban Revolution. For my stepfather this was the rebirth of his dream. He had come home defeated when the Spanish Civil War was won by the fascists. Here was his chance to be young again and relive that dream. He told my mother: “I am going to Cuba and if you want to stay with me, you’ll just have to come along, and so will the children” my little half-brother and half-sister. As I was part of the family, so did I.

While a high school student in Cuba, I found out that I was gay, which brought me great hardship. At the time there were ferocious campaigns against gay people there and for gay men, forced labor camps. It was a terrible time.

Finally, for complicated reasons, which I tried to explain in the book, which had to do with the relationship I was in, with my prospects for the future -I couldn’t get a job- I decided to leave after graduating from the University of Havana. In 1972 the world was still at the tail end of the Cold War and so in New York it was not cool to say that I had come from Cuba. If you were a Cuban who had escaped from Cuba, that was accepted by American society but if you were an American who came from Cuba, you were completely illegible.

Tell us about your ambivalent relationship with that thing called “the Cuban Revolution” as you lived it over those years. As a book about revolutionary heartbreak, Goodbye, My Havana holds powerful lessons for anyone who believes in freedom, justice, and progressive causes like equality. You seemed to be really onboard that train, trying to become the vanguard of that effort to build a new society, but then you and many other revolutionaries got thrown under the wheels of that train in the process. How did that happen?

Before going to Cuba at 16, I had been exposed to the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, the freedom rides in the South, the struggle against segregation, and I wanted very much to be a part of that. I was too young to go to the South so I got involved in the Bay Area in California, picketing with the NAACP. It was very important for me to be part of the struggle for equality. Experiencing that then and seeing now what’s happening with the Black Lives Matter movement is especially thrilling for people of my generation who struggled for those ideals in the 1960s.

This consciousness came from my stepfather Ted. As a communist and a Spanish Civil War vet, as a member of a community persecuted for fighting for equality for people of all colors and particularly for the descendants of slavery in the United States, he impressed his convictions on my mother and on me. When we went to Cuba, these were the ideals and passions that I fully embraced and brought with me as a young 16-year-old.

We arrived in Cuba with the expectation to live now in a country where these things had become real, where blacks and whites were equal, where the government, the people’s government, was striving to achieve literacy for the poor farmers in the countryside. People at the bottom of the social and economic ladder were to be uplifted with the opportunity to study, to go to the university. All this excited me very much.

And when did you start to notice the cracks in this idealized image of the Revolution, the internal contradictions?

At first, I didn’t see the contradictions. But over the course of those 10 years, I found that many things did not jibe with those early ideals. For instance, my family members in Cuba were classified as técnicos extranjeros, foreign technicians and dependents, a category slightly lower than diplomats in the social hierarchy. They were given special stores with ample food supplies not accessible to Cubans. There were foreign technicians from France, England, Canada, the United States and other western countries. Those from the United States were there quite illegally. Communist Cuba was a forbidden country for Americans to visit much less to live in.

The 1960s were years of acute deprivation for ordinary Cubans, with scarcity of food and most other consumer goods, as there is again today. But not for the foreign technicians. Besides exclusive grocery stores, they were given a country club in Miramar, by the sea, with an enormous swimming pool, sand, and an ample bar. What did you not see there? Cubans or foreigners of color. I became aware of that, and because I did not get along very well with my parents I spent as little time as possible with them or at their club. I lived my emotional life with my Cuban friends and lovers, both while in high school and then in college, and often slept in their homes. Most lived with their parents because of the acute housing shortages in Cuba, which exist to this day.

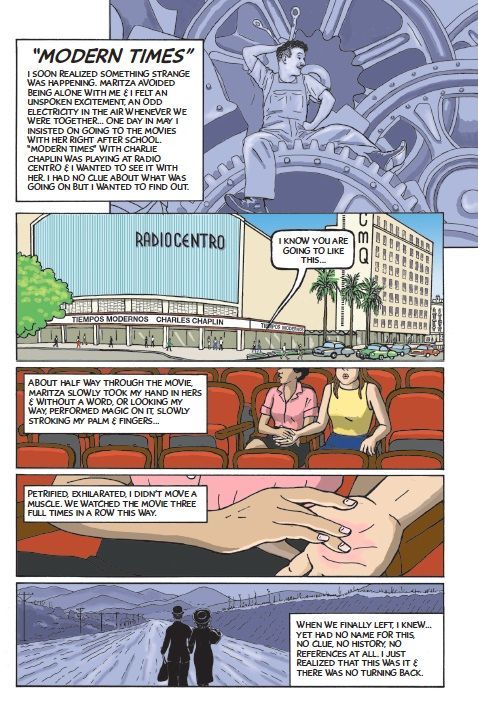

Another reason I spent most of my time away from my family was because three months after we arrived in Cuba in February 1962, I discovered I was gay. Oops! During the worst decade of repression against gay people in the history Cuba. Bad timing. I found this out while watching Modern Times in a movie theater on La Rampa, with my classmate Maritza. Here in this panel you can see when she first brought me to her home. This was the living room in the middle panel. There was one tiny bedroom past that wall. That was the entire home for three people. I soon learned that poor Cubans lived like Maritza’s family did, not the way my parents and all their foreign friends did. Now in this panel you see the movie theater where it happened. I had no idea, I’d never heard the word homosexuality or queer before, certainly not the word gay. But, I knew then in that movie theater there was no turning back.

I lived a schizophrenic life in Cuba. When I was with my parents and my brother and sister, it was a very elite existence. They didn’t interact with other Cubans outside of work. Foreigners like Ted served various purposes. One was the labor that they offered, in his case, he worked first as an electronics engineer for the Ministry of Industries, for JUCEPLAN, a commission that was supposedly laying out the plans for the country’s future economy. And then later he became a physics professor at the University at the behest of Che Guevara, then the head of JUCEPLAN. He also volunteered doing radio broadcasts in English aimed at the US to denounce the war in Vietnam. Later, he and the rest of my family, as well as others like him who were closely identified with the pro-Soviet faction on the left, were fired and sent packing after the “micro-faction affair” in the late 1960s, leaving me on my own in Cuba.

So, as a young, budding leftist but also someone who was then coming to terms with her own homosexuality, how did you see Che Guevara? Did you ever meet him, given that he was effectively your stepfather’s boss?

One day my mother said: “You’re going with us to the big celebration that they’re going to have at ICAP. Everyone will be there.” This was the Instituto Cubano de Amistad con los Pueblos (ICAP), the government organization that controlled all the foreign technicians from the non-socialist countries, who lived and worked in Cuba. I didn’t want to go, I just wanted to be with my friends and be free. But I did, thank goodness! I had the rather unique experience of seeing Che Guevara sitting at a table a few tables over. I was 17 then, and decided “I just have to do this, I hope it won’t get me into trouble.” I walked up and introduced myself and had a three-minute conversation with him, a memory that I still cherish.

Something that I did not know when I approached him with much alegría, with excitement and reverence, was that he was unforgivingly homophobic. He made that clear in later years when he promoted his goal of creating the “New Man” in Cuba. The concept of a “New Woman” was barely mentioned. The New Man was to be a manly revolutionary and never, ever gay, never soft, not like those suspect intellectual types. Very macho. And women were expected to behave according to strict feminine standards. Ambiguity was not to be tolerated ever. Those that did not meet these expectations were deemed unworthy to be a part of the revolutionary Cuban society that Che Guevara envisioned.

It took time to realize what this all meant on an existential, philosophical level. As a naïve 17-year-old I understood none of it. But in the ensuing years it had a lot to do with my disillusionment about life in revolutionary Cuba. I didn’t want to live in what evolved into an autocratic military dictatorship. There, I’ve said it!

There, you’ve said it.

Given this gradual shift in your understanding of the nature of the Revolution, it is quite intriguing to me that on the eve of your departure from Cuba in 1972 –in conversation with your lover Marta Eugenia– you were both still so utterly concerned with the image of yourselves as revolutionaries. In the heartbreaking exchange at the very end of your book as you’re planning your escape, you take the ferry across the bay of Havana and hike up to the Cristo statue that overlooks the city from the east, and at the very end of the conversation you ask her: “Can we still be revolutionaries?” And she responds emphatically: “Yes… They can’t take that away from us.”

I think you can translate the word “revolutionary” from that period, on that distant planet, to the word “progressive” in our current era. We were taught to equate being “revolutionaries” with being ethical, good, progressive people. While we were plotting to leave Cuba, we were wrestling with the fact that as a foreigner, and always a foreigner, there was nothing ethically amiss about my wanting to leave and go somewhere else. That’s what foreigners do. They live in other places. They come and they go. However, if you were Cuban and decided you wanted to leave, that amounted to treason. In this case we wanted to go to London because the British Council had offered Marta Eugenia a small summer scholarship that year to study Shakespeare in the UK.

We plotted a way for both of us to leave separately and then to meet in London, all the while struggling with the ethical question, were we betraying the Revolution by secretly planning to leave and live where we pleased? For Marta Eugenia, this meant leaving the only country that she knew and forsaking the revolution that she had always identified with since she was a young teenager. In the eyes of the society she knew this was immoral as well as dangerous and completely illegal. Just to have the thought of leaving was considered immoral. We discussed it for hours. What might it be like to not live in fear of harassment or worse for being gay?

There were other reasons for wanting to leave Cuba but that was a determining one. Besides, I couldn’t get a job there.

In the end, I never got to London because the Cuban authorities retained me for the duration of Marta Eugenia’s study abroad program. As soon as she returned, three days later, they put me on a cargo ship to Canada and that was the abrupt end of my life in Cuba. In the following years I couldn’t begin to explain what had happened. That’s why this book is here.

Based on your own experiences in Cuba and the other places you have lived, what is your take on the LGBTQ community there and on the movement in the US today?

When I returned from Cuba in 1972, something revolutionary was going on here in the United States. As a child of the Civil Rights movement it was one of the things that drew me here. That was the women’s liberation movement, and then the gay liberation movement, born after the Stonewall Riot in New York City in 1969. So, in 1972 there were a lot of interesting things happening which I found incredibly exciting and frankly, more revolutionary than what I experienced in Cuba, in certain ways.

Over the years, people have sometimes asked me, “if there was so much oppression in Cuba, how could you stand it? Why didn’t you just leave? Why did you live so many years there?” The obvious answer for me has always been, “Who knew I had any rights? Who imagined any gay person had rights?” To be gay in Cuba, and frankly in the United States in the 60s and before, was at best seen as shameful and at worst, criminal. Except for exceptional places, like bohemian neighborhoods in New York City, being gay was not cool either. A teacher in Kansas found out to be gay most likely would lose their job and their life would be ruined. One must keep that in perspective.

But in Cuba societal rejection by the state was much more severe. The expected relationship between the individual and the collective had been radically altered. The Revolution demanded that subordination. It was part of the revolutionary experience. In the States, as an individual, you lived your life for better or worse, but you were not directed by the government how to live it as was the case in Cuba.

In the 1960s, there was no such thing as the concept of gay pride. Pride, what pride? To be gay meant feeling painful embarrassment if you were outed, if you were suspected, if you were seen as gay. It meant humiliation and being filled with shame. That was not that different in this country then. If you were in a government position and you were found out to be gay, you were seen as a pervert. During the Cold War years, you could easily lose your job. This was nothing compared to the way gay people were treated in Cuba, but it was not cool to be gay anywhere in the world then. If you believed in the goals and ideals of the Revolution then you could only be embarrassed about your personal life and live it very privately, under cover.

One of the Cuban men sent to a forced labor camps in the 1960s was my friend Gustavo Ventoso, a respected classics student at the Escuela de Letras. One day in 1965 on La Rampa, in the middle of the day, he was having a conversation with Nicolás Farrey, our Latin professor. Suddenly a car pulled up, ordered him to get in and drove away. He disappeared, we didn’t know whether he was alive or dead for about six months. It turned out that he had been taken to an UMAP camp. The Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción were forced labor camps that operated in 1965, ‘66, and ‘67. Young men were taken away from schools, work centers, grabbed straight off the street if they showed any sign of being effeminate, if they had been denounced by their neighborhood Comité de Defensa, or someone had it in for them at work.

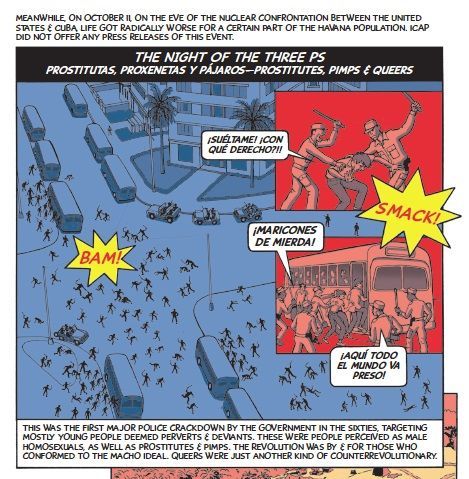

The first massive sweep had happened a few years before the creation of the UMAP. This was known as the notorious Noche de las tres Ps (The night of the 3Ps). This historic but unknown event took place in October 1962 precisely while the world was completely focused on the Cuban Missile Crisis. To my knowledge, this was the first time that the Cuban government carried out such a sweep of young people, of people who looked like freaks, who wore “indecent,” skinny pants, had long hair, who maybe had radios for listening to forbidden Miami stations, and most particularly if they looked like they were queer. This was a sweep of the so-called “prostitutas, proxenetas y pajaros” (prostitutes, pimps, and queers). Busses had been lined up on side streets, ready to pack in these people, which they did. This is one of the only events that I recreated in the book that I had been unaware of when it happened. I was in high school then and had just recently arrived in Cuba.

Before we close, I wanted to share something a bit more personal. Earlier, one of the things that you asked in our conversations was “what was it like to feel yourself to be a revolutionary back then and how do you feel now?” One of the ways that I wanted to answer that was by reading a prose poem that Marta Eugenia wrote; I wanted to give her a voice here today. She wrote this in 2004 when she went back to Cuba on a visit with her family. She had moved to Mexico in 1990 and lived there ever since, until she passed away in 2015. She wrote a series of prose poems where she essentially answers your question from her own point of view and experience.

Ok, fasten your seatbelts.

Marta Eugenia was a very enthusiastic revolutionary, she did her militia duty, she went to all of the trabajos productivos (voluntary labor), she was very active in neighborhood activities, she lived with her mother who was the head of the CDR on her block. So, we go now to 2004 when she went back to Havana and spent the summer. Even though she lived in exile, even all these years later, she still felt the need to write this book under a pseudonym, Mariana Lendoiro.

It was written in Spanish so I’m going to read a translation of just the very first poem entitled “Mi purga” or My Purge.

My Purge

The horror was that we were complicit then, we agreed to be marginalized, that we be despised, that they tear out our sweet and deep faith in the “betterment of humanity.”

We dropped to our knees and bowed our heads, a painful paradox that justified the executioners, because the Common Good was more sacred than the Individual Good. So, we did guard duty, went to voluntary labor, to the sugar harvests, the “emulations,” to the meetings, to the Plaza, to the UMAP, to the fields and to the coasts, to the military academies, the student circles, the wars, to the competitions, to hum in prison the hymns of the Fatherland.

We had to be better than the best in order to earn the same right, conceded in measures of crumbs, that we might be allowed a tiny piece of the “redeeming utopia.”

Humiliation was our sustenance; fright, our religion; guilt, the robe that covered our nakedness; fear, our constant passion.

They never accepted us. That smile, at times condescending, some moments compassionate, soon metamorphosed into a grimace of disgust or contempt, denying any value.

We are never going to belong. We never did. All those years, when like snake charmers we courted our rights, were years wasted. The labors of hate are more powerful than those of loving humanity. We are moral pygmies and will always be so despite them covering, with reluctance, our chests with tin medals. They sucked out our spirit and discarded it on the dung heap of undesirables.

And yet they demand of us the decency not to complain!

Lesbians, gays, young musicians, people of other faiths, eunuchs with their souls torn open, without remedy. It was all in vain. Now all that remains is a fevered and desolate emptiness and the years, orphaned of meaning.

That’s how Marta Eugenia felt in 2004. A lot of people got hurt and went through terrible times.

Thank you so much for sharing that.

So, I’ll return to your question about the contrast between being gay in Cuba vs. in the US. To be under the yoke of a government while being gay felt intensely oppressive, but we took it for granted as a fact of life. So, it felt intensely liberating after I came to the States in 1972. I had come on a brief visit in 1970 and experienced some of what was going on with the gay liberation movement and I wanted more. There was exciting change happening, I was attracted to that. It brought me to New York City.

And here you are, in New York.

Yes, here I am, I haven’t moved again since.

And I think this is your home, right? This is where you have your family, yes?

Absolutely. And what am I now? Am I a German-Cuban-American? Forget that. I’m a New Yorker. Y punto.

* This interview was originally done in two separate parts that straddle the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. The first was a public book presentation at the Instituto Cervantes in New York City on February 24, 2020, co-sponsored by the Centro Cultural Cubano de Nueva York (CCCNY). The second was a Zoom-enabled class visit by the author to Henken’s Latin American studies course at Baruch College on June 30, 2020. The two interviews have been synthesized here by Henken and then edited for clarity and accuracy by Veltfort. Note also that some of the questions here accredited to Henken were actually asked by his students in a Q&A with the author.

** The top photo in this post shows the School of Letters foreigners at work in the countryside in Cuba on April 1965. Connie is standing in the center.

*** The images are from the book Goodbye, My Havana. The Life and Times of a Gringa in Revolutionary Cuba, Stanford University Press, 2019.

I know two parents in heaven who are seeing their second son and showering him with kisses and hugs of congratulation and accolades of good wishes for a job well done. Extraordinarily done my little Cub Scout. I wish you only the best!

Mary, Thank you very much for your kind words. While this particular apple has fallen quite far from the tree my parents planted 49.5 years ago, their roots, my seeds, and our fruits keep us and our work connected. And also thanx for reminding me of the Cub Scouts and your being my den mother so many years ago in P’cola!