Even for those of us who know him, the professional life of Armando Lucas Correa seems as fast-paced and fragmented as his latest novel. Recently published in the United States by Penguin Random House, the experience of reading The Silence in Her Eyes can only be compared to running on a treadmill with ophthalmologist glasses, with brief stops to change the prescription lens again and again. Like on the treadmill, we end up almost out of breath; we strain to decipher what’s in front of us, only to realize in the end that we weren’t seeing anything.

In 1985, at the age of 25, Correa won the Premio 13 de marzo from the University of Havana with his play: Examen Final. In 1987, he was named editor of the performing arts magazine Tablas in Havana. In 1988, he won the essay prize from the Brigada Hermanos Saiz. In 1991, he moved to the United States thanks to an invitation from the Pratt Institute in New York. In 1993, he began working as a reporter for El Nuevo Herald in Miami. In 1996, at the age of 35, he won the Society of Professional Journalists award. In 1997, he became a lead writer for People en Español, the most widely circulated Spanish-language magazine in the U.S., and moved to New York. In 2007, he was named editor-in-chief of People en Español. In 2009, at age 50, he published his first book, In Search of Emma: Two Fathers, One Daughter, and the Dream of a Family (Rayo/Harper Collins), where he recounts the journey that led him to become a father to a girl conceived with a donor’s egg and carried via a surrogate pregnancy through in vitro fertilization. In 2016, at the age of 57, he published his first novel, The German Girl (Atria Books/Simon & Schuster), translated into more than 17 languages and distributed in over 30 countries, which would reach bestseller status with more than 1 million copies sold. In 2017, he was named Journalist of the Year by the Hispanic Public Relations Association of New York, and The German Girl was recognized as the best Spanish-language fiction book by the International Latino Book Awards. In 2018, AT&T awarded him the Humanity of Connection Award for his career. In 2019, he published The Daughter’s Tale (Atria Books). In 2021, In Search of Emma: How We Created Our Family (Harper One/Harper Collins) was republished in Spanish and, for the first time, in English. In 2022, he received the Cintas Foundation Award for Creative Writing. In 2023, he published The Night Traveler (Penguin Random House). In 2024, he will publish The Silence in Her Eyes (Penguin Random House).

I accompanied Armando to the presentation of The Night Traveler at Baruch College last year. Like his previous two books, it’s a historical fiction novel related to the MS St. Louis, a German ocean liner that set sail from the port of Hamburg in 1939 with 937 passengers, 930 of whom were Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazi regime. The Night Traveler tells the story of Lilith, a biracial, illegitimate child whose mother sends her to Cuba to save her from the racial policies of Nazism. Two decades later, it is Lilith who, after her husband’s execution by the revolutionary government, sends her daughter Nadine to the United States through the Catholic Church’s Operation Pedro Pan. The girl grows up in Queens with adoptive parents, and it is her daughter, Luna, who pieces together the loose ends of the family’s history.

The Silence in Her Eyes is Correa’s fourth novel, a psychological thriller about a young woman suffering from akinetopsia, or motion blindness, who, after her mother’s death, lives alone in her apartment in Morningside Heights in New York City. A few days ago, we presented this book at New York University. This interview brings together both presentations.

Both the theme of the Holocaust, which defines your first three novels, and the suspense genre, which might categorize your latest work, were very popular in Cuba during the 1970s and 1980s. The Cuban Book Institute published several international novels about World War II, the Holocaust, and the Warsaw Ghetto, and both its Radar collection and the Capitán San Luis publishing house, under the Ministry of the Interior, and Verde Olivo, under the Ministry of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, focused on the detective genre. Did that literary landscape influence your writing in any way? To what extent and in what manner?

I am a reader who writes, and, in some way, we write as we read. However, I don’t have a vivid memory of the books I read on that subject in Cuba. I didn’t grow up reading adventure novels, fantasy, pirates, cowboys, or crime stories. I read books that, while seemingly inappropriate for my age, shaped my literary taste. I devoured everything that came into my home—my mother was, and still is, an avid reader. From Ernest Hemingway, Gustave Flaubert, Stendhal, and Fyodor Dostoevsky to Italo Calvino, Raymond Radiguet, Stephen Crane, Ray Bradbury, J.D. Salinger, and Herman Melville, I read almost everything published by the Huracán and Cocuyo publishing houses. I remember once my mother sent me to stand in line at the bookstore next to the park at the Saúl Delgado pre-university school in Vedado because that day they were releasing A Farewell to Arms.

Cuban crime novels, with their excess of testosterone, were not for me. The most well-known writer in Cuba in the noir genre was an Uruguayan, Daniel Chavarría. His novel Joy came into my hands in the mid-seventies. The plot, focused on counterespionage and U.S. government attacks on Cuba, didn’t resonate with me. Later, when I entered the Higher Institute of Art, I became part of the “generation of the eighties,” fascinated by Marguerite Yourcenar, Milan Kundera, Yukio Mishima, Konstantínos Kaváfis, Jean Baudrillard, and Michel Foucault. We dreamed of being free and conquering the world. Socialist realism made us nauseous. We wanted to leave the country. They called it the Marco Polo syndrome.

My interest in World War II comes from my maternal grandparents. My grandfather was a history enthusiast, and my grandmother was pregnant with my mother when the MS St. Louis arrived at the port of Havana with over 900 Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany. Only 28 passengers were allowed to disembark, and I grew up hearing my grandmother say, “Cuba will pay dearly for the next hundred years for what it did to the Jewish refugees.”

Suspense and thrillers came to me through cinema. As a child, I read Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s A Twentieth-Century Job, a collection of his film chronicles, which he signed under the pseudonym Caín, and I became obsessed. I wanted to catch up with an art form as old as my grandmother, and I spent as much time as possible in the theaters. Since by the age of 10 I was already as tall as I am now, I could sneak into movies rated for ages 12, 15, and 16, when they changed the minimum age requirement. In Cabrera Infante’s book, I learned for the first time about Vertigo, my favorite film by Alfred Hitchcock, hailed as his masterpiece. I didn’t stop until I found it at the Águila de Oro, a cinema in Havana’s Chinatown. As Caín said, it is a great surrealist film. If The Silence in Her Eyes has any influence, it’s from Vertigo. Since that time, it has been in my mind, and I’ve seen it several times.

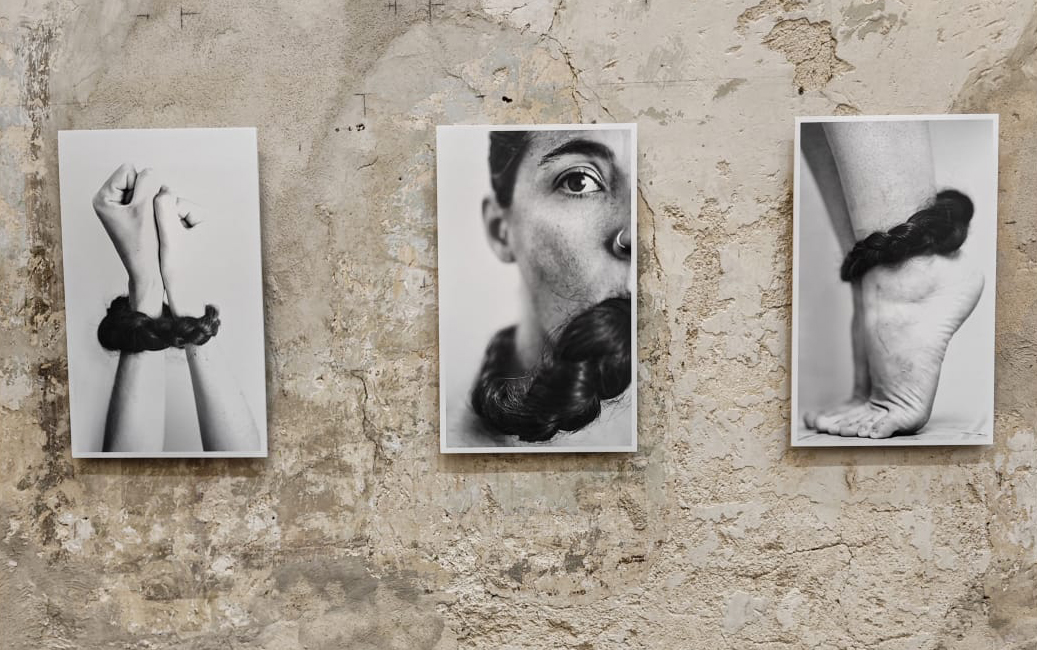

The protagonists of The Night Traveler and The Silence in Her Eyes are not classic heroines. We could say they are more like victims—of regimes of power and social structures. They are also imperfect, impure, sick individuals. For much of both plots, it seems as if they do not fight or even resist the prevailing order, but rather adapt or flee from it. Nor are they women with great personal or social ambitions. Their interests lie in the realm of the ordinary, the everyday. If anything, they even lack grand or eloquent names. Their names are childish, simple, and somewhat diminish them. What can you tell me about this?

The names of the characters in my novels are meticulously chosen. Beyond seeking names that can work in both Spanish and English—it even applies to my children, who are named Emma, Anna, and Lucas—these names have a specific meaning. For the protagonist of The Night Travelers, it took me months to settle on the name Lilith. The Night Travele is a book about the night; many decisions are made under the cover of darkness because, as Ally, Lilith’s mother, wrote, “At night, we are all the same color.” Ally, a white German writer, has a daughter with a Black German musician, a mischling or mixed-race child who, according to the Nuremberg racial laws, must be sterilized at the age of seven or sent to a concentration camp. Ally and Lilith move through a shadowed Berlin, avoiding the light that might betray the girl. Lilith means “dual” in the Judeo-Christian tradition, representing both light and darkness. She is a figure that entered Judaism from Mesopotamian religions and, over the centuries, has been associated with nocturnal birds and female demons, also tied to storms. She is even considered Adam’s first wife. It’s a name found in the Babylonian Talmud, the Epic of Gilgamesh, and even Goethe’s Faust. Lilith also represents the light of the moon.

This same approach applies to the names of the other characters, which, while not sounding epic, carry considerable weight.

As for the stories I tell, they revolve around great tragedies that I encounter everyday. Great feats and heroism bore me; I cannot connect with them. In my novels, the tragedy of the Holocaust transcends mere numbers, names, or historical events. I approach it through a mother, a daughter, a father—people like you and me. It’s my way of creating an emotional connection.

I’ve also noticed, during presentations around the world, that my books address the fear we have of “the other.” We are unsettled, if not outright rejecting, toward those who think differently than us, who believe in a different God, who have a different sexual orientation, or a different skin color or accent. Until we recognize and accept those differences, the world will not be a better place.

In your last two novels, the antiheroes are almost always male figures who, in one way or another, victimize the protagonists. Is this a conscious dichotomy? Do you think it would have worked the same way if you had reversed the genders?

In The Night Traveler, the figure of Franz is extremely complex. He was one of the characters I delved into the most. I even questioned whether I should develop him the way I did. The novel needed, at the very least, that antihero. It is a work of colors and shades; nothing is black and white. The plot unfolds in shadows, if not complete darkness. Nothing is as it seems. Franz is an unconventional Nazi, different from the stereotypical image we usually find in novels and films. He resembles, in a way, Thomsen from The Zone of Interest by Martin Amis. Franz is a handsome, calm, well-mannered young man—educated, a poet, in love with Ally, and protective of Lilith. He even maintains a close relationship with his literature professor, who appears to be gay. His Nazi and military status is circumstantial, shaped by the era he lived in and by a mother who was a fervent supporter of Nazism. However, his kindness and even his humanism do not redeem him or save him from becoming a monster. That dichotomy characterizes many of the characters in my novels.

I remember during a presentation of The Night Traveler in Australia, someone in the audience asked me why Franz did what he did. My answer was, “I don’t know.” I believe there are no definitive answers as to why Hitler acted the way he did. It’s complicated to trace the origins of evil.

In The Silence in Her Eyes, the narrative changes. Who victimizes whom is only revealed at the end.

In The Night Traveler, the protagonists are biracial, bilingual (sometimes speaking more than two languages), and binational. The novel revolves around displacements and changes—of continent, country, city, language, political systems, and surname. This often makes identities seem fluid, like a garment that can be put on or taken off. The Silence in Her Eyes, on the other hand, takes place almost entirely within an apartment, with the rest of the scenes set either in the building or just a few blocks around it, though the final scene takes place in a Brooklyn subway station. What led to this change, and how did you approach it from a literary perspective?

My three historical novels are about uprooting and rejection. They move from city to city, country to country, without the protagonists ever being able to put down roots. It has to do with the feeling of being a refugee, an exile. “Life is elsewhere,” said Milan Kundera. In The Silence in Her Eyes, the opposite happens. It was a challenge for me because I like to develop multiple characters, themes, and sub-themes that intertwine. That complexity gives me freedom.

While in the historical novels I cover decades, in The Silence in Her Eyes, the plot is confined to an apartment in New York, to a neighborhood, and everything takes place over the span of a few months. The world is reduced to what the protagonist sees and thinks. That was the greatest literary challenge—to narrate from Leah’s perspective.

This book, like the previous ones, went through multiple versions. For instance, it wasn’t until the English translation that I decided to spread the chapters on the floor of my apartment and move them around like puzzle pieces. It was then that I decided to stick to a linear narrative, which was a significant change from the original version. That led me to opt for the first-person perspective. Since the protagonist cannot perceive movement—due to her akinetopsia—what she sees is a fragmented world of static images, I decided to shorten the chapters so that the ideas would progress discontinuously. The challenge was to maintain the rhythm and achieve an abrupt and unexpected ending. This meant that the book ended up being reduced to half the pages I had initially written.

You spent a lot of time researching while writing both novels. Was it easy to transition from historical research to medical research? What method do you use in both processes? What do you gain personally from the whole process?

The research for The German Girl took me more than ten years. My collection about the MS St. Louis grew so much that I ended up donating many of the original documents, objects, and photographs to the small Holocaust museum in a synagogue in Vedado, Cuba. Not to mention the numerous trips to Berlin, Hamburg, Krakow, Paris, Auschwitz, and Havana. I can’t begin writing until the research is well underway. That includes reading what was being read at the time, watching the films, listening to the music of the era, and even knowing what type of paper was used to line the walls or what perfume was in fashion. It’s something I come to without intending to, I believe. Much of what I study and research I never even use, but it helps my brain navigate new territories.

The research of the MS St. Louis has given me many things. I’ve become friends with three survivors, who often accompany me at my presentations. The tragedy of the MS St. Louis and the role that Cuba, Canada, and the United States played are now widely known, and I contributed my bit by helping Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologize to the survivors of the MS St. Louis in the House of Commons in Ottawa in 2018. On that occasion, I helped his office locate and invite seven survivors, now elderly. One of them, Ana María Karman, lives in Toronto and is a Canadian citizen. I was there that day in November with all of them. It was truly moving.

If with The Daughter’s Tale, my second historical novel, I spent months studying the heartbeat—I could almost read electrocardiograms with the precision of a cardiologist—for The Silence in Her Eyes, I devoted myself to studying the brain and its mysteries, specifically the condition Leah suffers from: akinetopsia. My eldest daughter was in her final year of high school and wanted to study medicine in college. My husband and I organized a visit, with a pathologist friend, to the morgue of a university in New Jersey to dissect and study a brain. I didn’t stop asking questions. We then returned with the whole family. In the end, I was fascinated, and my daughter hated it. She abandoned her dream of studying medicine and ended up enrolling in mechanical engineering at college.

Recently, I received an email from a reader whose eleven-year-old son suffers from akinetopsia. The reader assumed I had researched the condition extensively and thought I was an expert on the subject. I felt bad that I couldn’t offer him the help he was seeking.

During the writing of your historical novels, you dedicated yourself to collecting objects related to the events that serve as the backdrop to the plot. Have you now become a collector of medical instruments, potions, and daguerreotypes?

Of course, I still keep some of the essences I acquired, including a bottle of bergamot, a scent that is almost another character in the novel. I spent months searching for a daguerreotype of a blind girl, and I finally found and purchased it at an auction. I still keep it close to where I write.

Of all your works, The Silence in Her Eyes is the least Cuban. While almost none of your protagonists are Cuban, part of the plot of your previous novels takes place on the Island. In The Silence in Her Eyes, apart from the nationality of a relatively secondary character, Cuba is nowhere to be found. Does this mean that, after more than three decades living outside of Cuba, you’ve finally managed to detach yourself from it?

I am Cuban, and I will never stop being Cuban—that is my essence. But I rarely look back. Cuba is, at least for those of us who live outside of it and are exiled or refugees, a torment, an endless tragedy. That’s why I avoid living anchored to the past. I prefer to look toward the future. Nostalgia is a sickness. I write about what really interests and motivates me. Topics related to Cuba are too commonplace for me. If I dedicated myself to writing about them, I would probably get bored. After I left Miami, where I worked for five years right after arriving from Cuba, writing about Cuba for El Nuevo Herald, I promised myself that the Island would no longer be the main focus of my life or my source of income. Then I joined a corporate-level company in New York, where there were maybe only a couple of Cubans, and the subject of Cuba was rarely covered. This doesn’t mean I’m uninformed about what happens in Cuba; my mother and sister live in Miami, and Gonzalo, my husband, stays up to date with everything happening there and helps however he can.

In my books, with the exception of The Daughter’s Tale and The Silence in Her Eyes, Cuba is present in some way. In The German Girl, the Island surfaces through the eyes of a twelve-year-old German Jewish girl who arrives in a city that is hostile to her. In The Night Traveler, which I consider the most Cuban of my novels, Lilith arrives in Havana at the age of eight, and there she grows up, studies, falls in love, gets married, and has a daughter. Even Fulgencio Batista is a character in the novel. In The Silence in Her Eyes, Antonia, the woman who takes care of Leah, is Cuban. It’s something, at least.

You’ve been dedicating yourself full-time to literature for two years now. How has your departure from People en Español affected your writing?

My departure from People en Español, where I worked for 25 years, was abrupt. Sometimes, a push is necessary to make a change. I had three books under contract with Atria Books at Simon & Schuster, and between the pressure from work and the publisher, not to mention the stress and confinement of the pandemic, I was feeling a bit suffocated.

For the past two years, I no longer write at night, which was the only time I had to do it before. Now, my schedule is from nine in the morning to three in the afternoon, and if I want, I can spend the day reading. Reading and writing have become my job. I have the freedom to go out and walk more than four miles a day. In a way, I feel freer. At first, there’s always a bit of disorientation. When I think about returning to the corporate world, it gives me chills. But one should never close doors. Still, I always need to have a project on hand that presents a challenge. I need to stay busy, even if that means writing three books at the same time. It’s something I can’t escape.

According to People en Español, you’re negotiating the film adaptation of The Silence in Her Eyes. This would be the second of your novels in the process of being adapted for the screen. What can you tell us about both projects and your expectations regarding directors, actors, etc.?

The German Girl is under contract with Hollywood Gang Productions for the development of a series. It seems they already have a director working on the script. The Silence in Her Eyes is in an earlier phase, seeking funding. It’s a long and tedious process that I prefer to stay out of.

Can we expect a novel about the homosexual experience in 1980s Cuba?

Never Again Will I Live on an Island, a novel I wrote and finished in the mid-1980s and revisited almost ten years later, relates to my generation. It’s about a group of theater and fine arts students living in the heart of Havana’s nightlife. It’s a very pretentious book—I was 25 when I finished the first draft—and it addressed gay life in Cuba, with a bit of Three Trapped Tigers, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and numerous quotes from Marguerite Yourcenar. The cover featured the St. Sebastian that Consuelo Castañeda recreated in We Don’t Need Another Hero. A true “mental jerk-off” with a lot of “meta-baggage,” as Arturo Cuenca would say, which will never see the light of day. I have too many ideas for new books, and stopping to work on something old just makes me lazy.

What are you working on now?

I’m in the middle of three projects at once. My novel What We Once Were is set to be published by Atria Books in 2026. It’s ready to be sent for translation in about a month. Then comes an intense process of editing in English, which will take me at least a year. After that, I’ll have to apply all those changes to the Spanish version. It’s exhausting work, draining, but in the end, I’m a bit of a masochist and enjoy it a lot.

What We Once Were begins in Galicia in 1898, after the defeat of the Spaniards in the Spanish-American War, with two teenagers who board the transatlantic ship Isla Panay, nicknamed the “ship of death,” heading to Cuba. On board, they marry out of convenience. They disembark in Santiago de Cuba and move to Guantánamo, where they live in a boarding house owned by a Galician woman.

What We Once Were is the story of my maternal great-grandparents from their arrival in Guantánamo, back when it was a village without roads. They witnessed the creation of the U.S. Naval Base and the arrival of electric light, among other events that turned the village, as they called it, into a cosmopolitan city for the time. The family saga spans the birth of the republic, experiences democratic regimes, suffers coups, violence, internal wars, and even a brief exile in New York.

After the triumph of the Revolution, the protagonist returns to Havana and settles in the mansion in Vedado that she had started building during Batista’s government. The novel ends in Havana in 1999, as the world falls apart. It’s the story of my family up until 1959. From there on, I change the destinies of all of them. One of the protagonists, who closes the novel, is gay.

I have another novel in development, with more than 30,000 words written, which has also been acquired by Atria Books and should be released in 2028. The Islands of Neverland picks up during World War II through the story of four children, each born on different islands: Peacock Island on Lake Wannsee, on the outskirts of Berlin; Jersey Island in the English Channel; Cuba; and Manhattan. This time, the protagonists are boys, a promise I made to my son Lucas years ago.

The project currently consuming me is “Emergency Exit”, a novel I can’t stop writing. Set in the early 21st century in New York, it revolves around five characters who don’t know each other but are united only by their family losses: an autistic young man who graduated from Columbia University, an Orthodox Jew from Brooklyn, an elderly Black woman from the Bronx, a Cuban raft refugee, and the son of Syrian terrorists. A neuropsychiatrist, a Holocaust survivor, connects them on the day of her death, turning them into each other’s emergency exit. According to her, emergency exits are also doors of entry. The story begins with the fall of the Twin Towers.

If you had just arrived from Cuba now, would you try to become a writer?

As I told you, I consider myself a reader who writes. I never saw writing as a profession per se. If as a child I read Platero and I, I would end up writing a story about an animal in the style of Juan Ramón Jiménez. At the age of ten, I joined a literary workshop at the Casa de la Cultura at 23 and C, in Vedado, which later became an art school. I think they allowed me to participate because of my height, as I seemed older, since only what I considered elderly people—potential writers who had never published—attended those night meetings. The curious thing is that those “elderly” workshop members were probably no older than 35. While I recognize the value of literary workshops and their usefulness, I admit they don’t resonate with me. I don’t like the idea of reading a chapter and then listening to critiques. I prefer to read rather than listen to what others read; I simply can’t concentrate. That’s why I don’t like audiobooks. I haven’t been a fan of radio dramas either; in my childhood home, we only listened to music and news on the radio.

The closest I came to being a paid writer was when I studied for a Bachelor’s degree in Performing Arts, specializing in Theater Criticism, at the Higher Institute of Art in Havana. I had the honor of having Rine Leal as my mentor, and from my admission (he chaired the admission jury), he informed me that he would also be my thesis tutor. For a year, I visited his attic near the park on Calzada Street, across from the Amadeo Roldán Theater, to show him the progress of my research on the playwright Carlos Felipe. It was an experience akin to a master’s degree. Despite his predictions about my future as a writer, I didn’t pay much attention.

The first thing I published, before graduating, was an essay on Roberto Arlt in the magazine Conjunto, edited by Carlos Espinosa. From Carlos, I learned that more than clever ideas are needed to write. I deeply admire him and believe that Cuban literature owes him much for his work as an archivist and rescuer, especially of writers like Antón Arrufat, Virgilio Piñera, and José Lezama Lima. The next thing I published with him in Conjunto was a summary of my thesis on the dramaturgy of Carlos Felipe.

My career as a theater critic began in the magazine Tablas, where I was an editor. I also contributed to the Spanish magazine El Público, for which I was paid for my writings. At the same time, I was writing fiction, without imagining the fate of those texts that accompanied me when I left Cuba. Upon arriving in Miami, I wrote for El Nuevo Herald and then for People en Español.

To give you an idea, the final chapter of The German Girl, where Hannah, at 87 years old, walks along Paseo Avenue to the seawall with a small indigo blue box, was written in 1987.

Therefore, my advice for those aspiring to become authors is simple: write every day and, most importantly, never stop reading. I distrust those who one day quit their job, declare they will dedicate themselves to writing, and sit down for the first time in front of a blank screen. Someone who writes does so because they have written their whole life. They may not have dedicated themselves to it professionally, but they should have written several thousand words. It’s impossible for a child to proclaim they will be a novelist before they have learned to spell. They could dream of being a pilot, firefighter, or lion hunter, but a writer, no.

If I had just arrived from Cuba, I would continue writing, although if I had left younger, I might have pursued mathematical calculations or coding. But that doesn’t mean I would have abandoned writing or reading; one activity does not exclude the other.