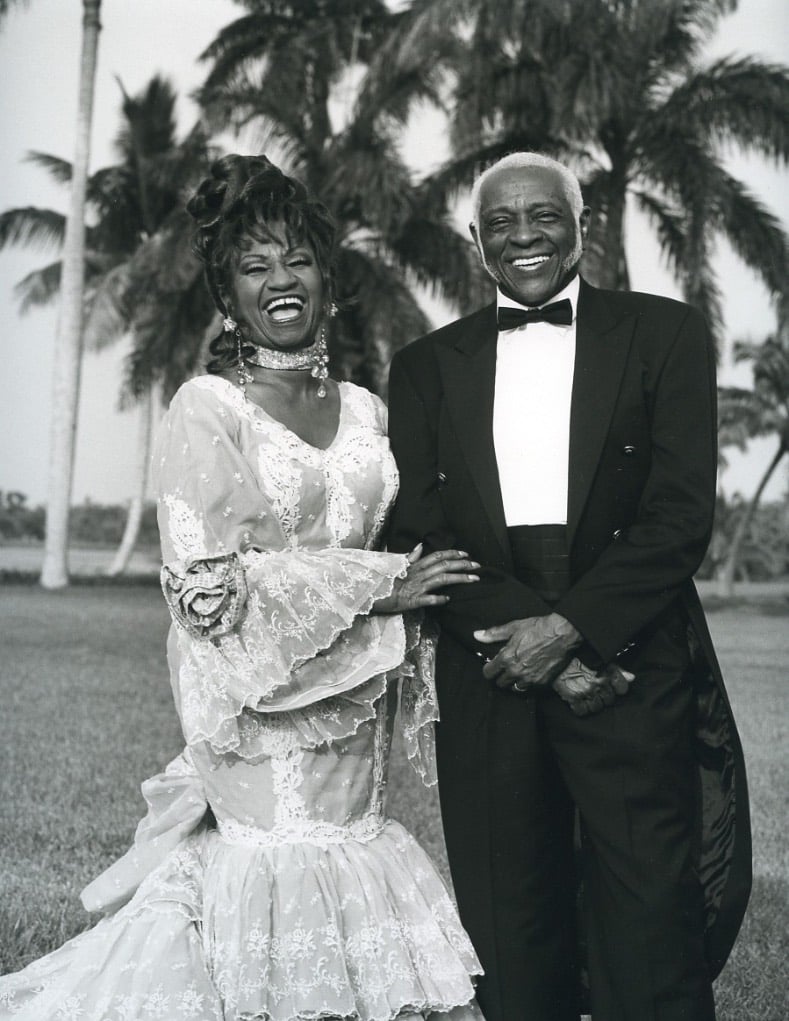

When Alexis Rodríguez-Duarte and his partner and collaborator Tico Torres decided to turn a fashion magazine assignment for L’Uomo Vogue into a tribute to their parents’ Cuba from Miami, they could not have imagined that they were challenging not only their history, but also that of the magazine and Celia Cruz herself. The photos from that session served as the model and inspiration for artist Phebe Hemphill to design the coin dedicated to “La Guarachera de Cuba,” the “Queen of Salsa,” as part of the 2024 American Women Quarter series. This is the latest milestone for the now-legendary photo of Celia and the royal palms, which since 2016—printed in inkjet—has been part of the permanent collection at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. (managed by the Smithsonian Institute), where portraits of the most illustrious and famous figures in the United States are exhibited.

“‘I am the Voice of Cuba, Guantanamera!’ That’s the title we wanted to give the photo. It couldn’t be anything else!” Alexis Rodríguez-Duarte tells me, excited and eloquent. Alexis is a photographer; Tico was the true art director of the photoshoot, as described by Cabrera Infante, responsible for the mise-en-scène and the critical eye behind Alexis’ lens. They are married and have been together for over 40 years, sharing both a life and a profession.

In their apartment in New York’s West Village, Celia and Cuba are everywhere; a mix of cosmopolitanism and Cubanness in its most modern and personal expression: photos—of course—vinyl records in abundance, books, posters, magazines, objects, and reminiscences of flavors and smells that once felt distant but returned to them thanks to Celia Cruz.

The photographer recounts: “Tico and I had the idea to propose to Alex González, then art director of L’Uomo Vogue, a fashion photo series under the concept of Miami Cuban Style. By then, we had fully returned to our roots with great passion. We arrived in Miami from Cuba with our families in 1968 on the ‘Freedom Flights,’ still children, and we grew up in Miami: one in Hialeah and the other in Little Havana. In our teens, as Cuban-Americans, we wanted to be more American, and we worked hard to achieve that. Americanizing ourselves was part of the integration process, just like it happened with the Italians and other nationalities: we wanted to be Americans.”

“Celia was our parents” music; she was the Celia we heard at the weekend parties at Tico’s house, and in a way, it was music we associated with the past,” Alexis Rodríguez-Duarte recalls. “It was Celia herself who reconnected me with my identity and the legacy of where I came from. Celia made us proudly return to the roots and origins through learning and searching.”

He also recalls the amazement of their first encounter with the Cuban diva: “In 1988, we were living in London for a short period and saw posters on the subway announcing her concert at Hammersmith Palais, feeling incredulous and stunned by what we thought was an odd and unlikely event for the London audience. Our curiosity grew, and we decided to meet her. Meeting Celia was defining with incredible simplicity, she answered the phone herself and agreed to speak with us, two Cuban-American boys. She wanted to know everything about us and our families,” the artist reminisces. “We were in a precarious situation in London, so much so that we couldn’t afford theater tickets. We were embarrassed to tell Celia when she asked if we would be at her concert. But her response gave us hope: ‘I can’t promise anything, but I’ll see what I can do. Don’t worry.’ The next morning, she called back and told us to stop by the theater’s box office. There, we found not only two tickets but also two general VIP passes. We couldn’t believe it! The concert was a tremendous success—she was magnificent, electrifying the famous venue—and we, who were right by the sound console and even went backstage to talk with her, made the mistake of not bringing a camera! That encounter marked the beginning of 15 years of collaboration, learning, and friendship that shaped our lives and careers.”

Six years after that London episode, the project proposed by Alexis and Tico was accepted by the Italian fashion magazine, on the condition that Guillermo Cabrera Infante would write the accompanying article. Alexis and Tico boldly assumed the eminent Cuban writer would agree, even though they had never met him. The story had a happy ending: Cabrera Infante agreed to collaborate on that and other projects for the magazine and the photographers, writing an essay titled “Sun Over Miami.” His writings and a series of photos of the great Cuban author, taken by Alexis and Tico, who went on to build a friendship with him and his wife, Miriam Gómez—are the best proof of the success of that venture.

For the 1994 session, Celia no longer wore her stylized recreations of the Cuban bata, known as the guarachera or rumbera costume, though I personally don’t like that description. She had transitioned to a pop look, inserting herself more into the modern music scene than traditional Cuban and Afro-Caribbean music.

“Despite that, I wanted to choose that dress because our fantasy was the Celia of our parents, the one from the ‘60s, the image they held in their memory. With this direction, Celia picked out several dresses along those lines and brought them to Miami. Among them, I chose this one. She had worn it before for some performances, but it was perfect. The dress later had an eventful journey, which Omer [Pardillo] can explain better than I can,” says Tico Torres, always mindful of the styling and scene for the photo shoot.

It was an elaborate lime-green Cuban bata, filled with lace and embroidery, created by Cuban designer Enrique Arteaga, then residing in New York. The downfall of the short-lived Fashion Café at Rockefeller Center almost took the mythical bata with it, as Celia Cruz had loaned it for display at the supposedly promising venture that launched in December 1994, with much fanfare, by supermodels Claudia Schiffer, Naomi Campbell, and Elle McPherson. “When the Fashion Café closed in 1998, the dresses on display were sold on an internet platform,” explains Omer Pardillo, who was Celia Cruz’s manager. “A friend alerted me in time, and I was able to buy it back. Today, it is part of the Celia Cruz Estate/Celia Cruz Legacy Project.”

The Cuban bata, reinterpreted, enhanced the symbolism of the setting chosen for the photo session; the fusion of tradition and modernity lay in the accessories: high, gravity-defying platform shoes—already a Celia Cruz trademark—and the intricate updo, known as the “María Caracoles” style by Cuban women in the ‘60s, created by Olazábal, a famous Cuban-American stylist from Miami.

“My Hasselblad, the very one you see here,” and he points to a corner of the living room: “with that same lens, captured that image of Celia,” says Alexis Rodríguez-Duarte. “Although we live in the digital age, we are film guys, from those—or these—cameras with rolls or reels. The images astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin sent from the Moon were taken with a Hasselblad. I grew up with film, and I still use it, in addition to digital cameras… But we think there’s no comparison in terms of results.”

“I like to talk with the person I’m photographing,” says the author of the iconic snapshot. “And when I was about to press the shutter, I asked Celia what her favorite Cuban song was. She opened her arms, looked at the sky, and with all the power of her voice, she began to sing: ‘Guantanamera, guajira guantanamera, / guantanamera, guajira guantanamera…’ That’s the real story, despite the various interpretations that have been attributed to the moment captured in the photo. Celia wasn’t invoking her African ancestors or the orishas, no matter how often that has been repeated in various sources,” he insists. “That’s how the entire photo session went: Celia singing a cappella, giving us the privilege of her voice.”

1994 was also the year that Celia received the National Medal of Arts from President Bill Clinton, a distinction created by the United States Congress, which is the highest honor granted to artists and patrons of the arts in the country. Alexis and Tico witnessed many other transcendent moments in Celia Cruz’s life, particularly in New York, Miami, and Paris: with their camera, they immortalized concerts, personal anniversaries, and various significant occasions that marked her integration into American society and recognition of Celia Cruz’s artistic and human stature in her adopted country. This recognition was not only expressed through official decorations but also in popular affection, such as when she and Pedro Knight were chosen as Grand Marshals of the Cuban Day Parade in New York in 1999, or when she performed as a special guest of Aretha Franklin at the legendary concert VH1 Divas Live: The One and Only Aretha Franklin at Radio City Music Hall in 2001.

* * *

Twenty-nine years after that memorable photo shoot, the United States Mint announced the selection of Celia Cruz among the notable women to be honored in the 2024 edition of the American Women Quarter program. Among the photos sent by Omer Pardillo, executor of the Celia Cruz Estate, for the design of the image on the reverse of the quarter commemorating “La Guarachera de Cuba,” were those taken that day in Miami by Alexis Rodríguez-Duarte and Tico Torres.

In the small cupronickel disc weighing 5.670 grams, with a diameter of 24.26 mm and a thickness of 1.75 mm, the artist Phebe Hemphill captured the essence of Alexis and Tico’s photos, brilliantly synthesizing identity and unique symbols: the perpetual joy in her smile, the updated bata cubana dress, which, though a stage costume, remains one of the most enduring stereotypes of old Cuban identity, the exaggeration of her hairstyle and earrings, all topped off with her famous cry that calls for excitement: “¡Azúcar!”

“This is very surreal for us,” says Alexis Rodríguez-Duarte. “After working for the world’s top fashion outlets, after photographing so many celebrities [he doesn’t mention it, but his lens has captured Jeff Koons, Madonna, Daniel Arsham, Andy García, Carolina Herrera, Gloria Vanderbilt, and many others], we never imagined the transcendence of what we had done, which would manifest in something as extraordinary as Celia’s coin.”

Hemphill’s design has made it possible for the first time for not only a word in Spanish, with perfect spelling and punctuation, and a wardrobe element evoking Cuban identity, to appear on a U.S. coin; Celia Cruz is also now the first Afro-Cuban woman whose image is sculpted on a coin, not only in the United States but in any country. Of course, this includes Cuba, where Celia was born and laid the foundation for her career, and whose government still condemns her to official censorship and disdain.

These symbols will pass from hand to hand, etched on each of the 500 million quarters the United States Mint has decided to produce and circulate in this round. Without a doubt, it is one of the most significant achievements of the most universal Cuban. It reflects the recognition of her impact on American culture, a result of her constant defense of her native country’s musical traditions and her intelligent approach to making them accessible to wider Latino and Anglo audiences. Her involvement in the most noble and urgent social causes — such as the fight against cancer and HIV — her financial support for the musical education of underprivileged children, the respect from American colleagues for her genuine and masterful art, and her human values, all contribute to the significance of Celia Cruz being featured on this coin.

For Alexis and Tico, the inspiration that the Queen of Salsa represented has transcended the imaginable limits: the reunion with their roots, that return to their origins, became their life’s purpose. Since 1993, successive projects have led them to document the Cuban diaspora in the United States and commit to preserving Cuban exile history through visual memory. One example is their memorable exhibition Cuba Out of Cuba: Through the Lens of Alexis Rodríguez-Duarte in Collaboration with Tico Torres in Miami, 2014.

Their educational work at specialized institutions, assignments from prestigious international media (such as The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, Town & Country, and Harper’s Bazaar), and a series of artistic male nudes are further testaments to their dedication.