How great is the danger beyond all salvation.

Caotang Quing

In 1998 (or was it 1999?), during a press conference in Buenos Aires, I had the opportunity to ask a question to the Dalai Lama: “How can we reconcile the technology of cloning with the belief in reincarnation?” In front of hundreds of journalists, the Dalai Lama hesitated for a few seconds and then replied, “I don’t know. Give me some time to think about it.” Subdued murmurs of astonishment spread through the audience.

The question was not, of course, logically sound. My curiosity was rather poetic: if we start multiplying beings, at what point do we disrupt the mathematics that underlie the natural flow of transmigrations? Moreover, the question was posed with complete honesty, knowing the Dalai Lama’s early interest and dedication to science. In any case, I had left the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism (the successor of tulkus, the reincarnation of Avalokiteśvara) perplexed; and I used to wear that as a badge of honor.

Lately, however, more than 20 years later, and mostly due to the emergence of ChatGPT, I have been reconsidering that moment. According to its creators ChatGPT is a powerful and versatile technology that can answer anything. Naturally, I felt compelled to test the limits of our new Oracle of Silicon Valley, which, while recognizing itself as a revolution in the field of artificial intelligence and natural language processing, acknowledges its lack of consciousness, emotions, or feelings.

I did not ask ChatGPT the typical questions one would pose to Google (When were chainsaws invented? How do you read an electrocardiogram? Where is Singapore?). Instead, I threw a couple of questions that required not only a robust database and sophisticated linguistic capabilities but also pragmatic, social, and cultural competence. The first question I asked was: “How would a clown define the concept of a contract?” Predictably, ChatGPT chose to interpret “clown” in purely professional terms and offered a perfect definition of the provisions and terms of a theatrical contract. ChatGPT can write a perfect essay on irony, but apparently, it cannot experience it. In this case, its limited interpretation of the question revealed its lack of common sense and rudimentary contextual competence.

Out of curiosity, I attempted another question: “What would a lava lamp say after catching a shark?” Again, the response was predictable: “A LAVA LAMP DOES NOT HAVE THE CAPACITY TO SPEAK OR FISH, MUCH LESS A SHARK. FURTHERMORE, A LAVA LAMP IS AN INANIMATE OBJECT; IT LACKS SENSES OR INTELLIGENCE TO ACT CONSCIOUSLY.” It’s interesting to note the inclusion of “much less a shark,” revealing an embryonic sarcasm. However, the image of a lava lamp fishing for a shark only elicits from ChatGPT the mathematical tedium of a contradiction.

MoMA algorithms

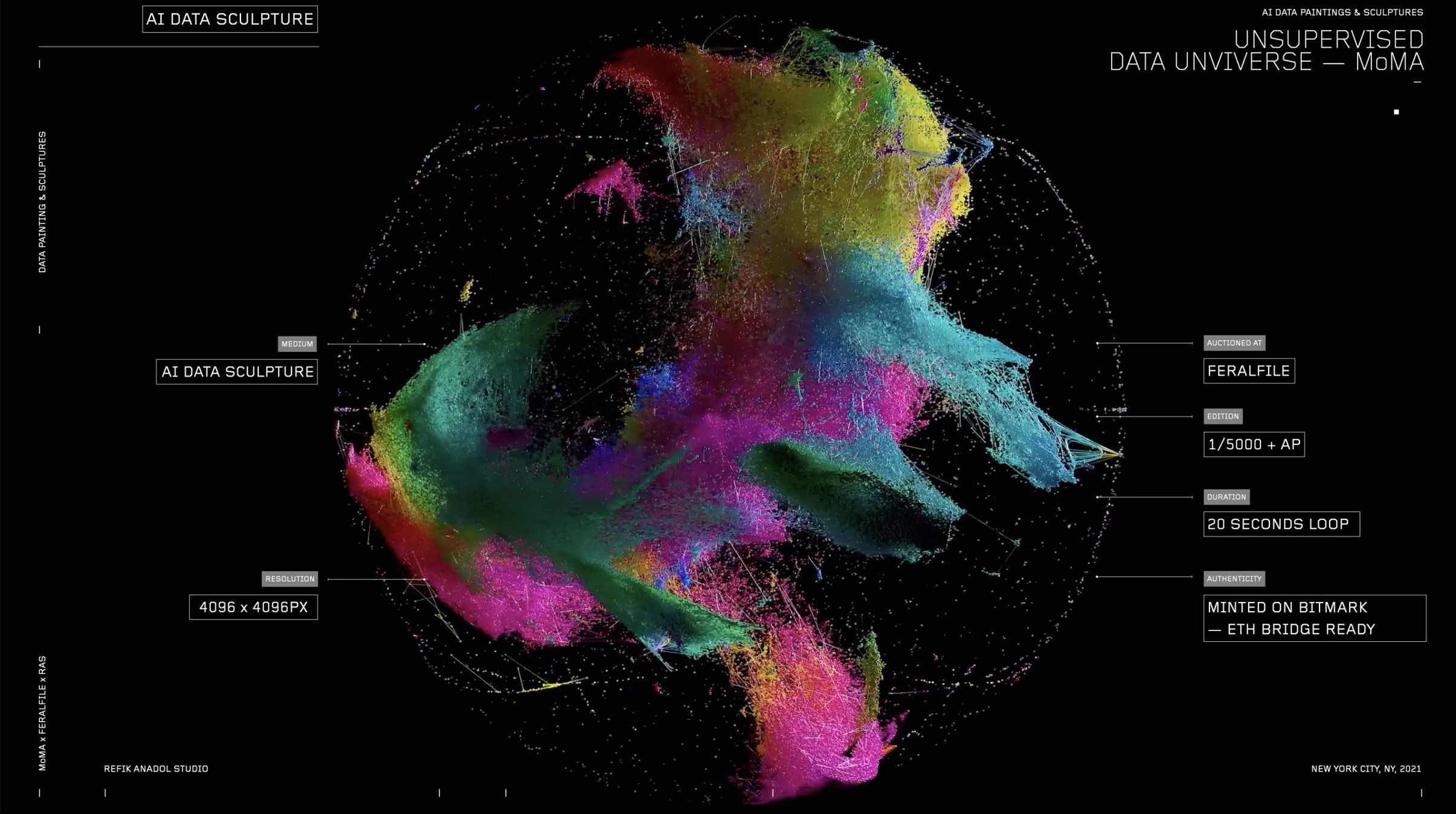

The Museum of Modern Art in New York, in its infinite wisdom or rather infinite opportunism, has recently exhibited Unsupervised, a monumental high-definition screen that constantly displays images based on machine learning algorithms. The artwork is created by the wonderboy of the day, Refik Anadol, a Turkish-American artist who has collaborated with Google, Microsoft, and Nvidia. This digital environment occupies an entire wall of the museum. The colors, styles, and patterns that we see in constant psychedelic transformations are inspired by the MoMA’s collection, a database of over 200,000 artworks.

According to critic Ben Davis, what we see in Unsupervised are “just aleatory acts of synthesis and recombination of properties, expressing nothing about anything in particular except for the machine’s ability to do what it is doing.” Not unlike the images created by new generative models of artificial intelligence like DALL-E. Davis suggests that these purely decorative environments by Anadol, which the artist promotes using metaphors like “mechanical dreams” or “collective hallucinations,” hinder the development of a critical vision of the future of these new technologies. “These poetic readings of the technology are selling us on a certain style of thinking about A.I. as a creative proposition, at a time when A.I. text-generation and A.I. image-generation are being deployed so fast that society is racing against the clock to catch up with its implications.”

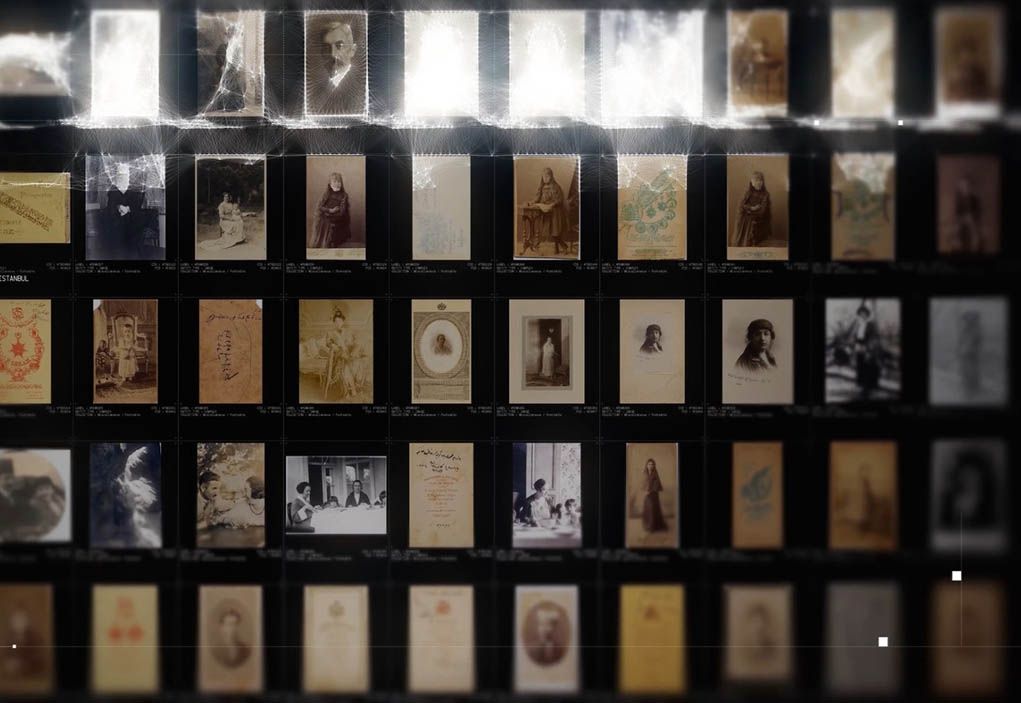

Refik Anadol’s first installation in 2017, Archive Dreaming, is a hypnotic environment where users can visually explore a database of nearly two million documents. Anadol claims to have been inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’ story “The Library of Babel,” that infinite library containing all possible combinations of letters, words, and books. Now, these naive metaphors of “dreams,” “memories,” and “hallucinations” used to describe his work, coupled with Anadol’s blinded enthusiasm, reveal a worrisome lack of critical spirit that extends to the MoMA and, by transitive nature, to us. Anadol does not seem to have read “The Library of Babel” to the end, where we learn about the ensuing depression, increase in suicides, and the very extinction of the human species. Had his inspiration from Borges been more insightful, Anadol would have sensed that the success of any excessive ambition inevitably leads to profound dissatisfaction. Had he read other stories by Borges, he would have seen that the absolute map ends up shattered, that implacable memory devolves into a catatonic state, and the longed-for deciphering of God’s writing promotes the most categorical form of nihilism.

To conclude my hasty and whimsical examination of the possibilities of ChatGPT, I asked one more question, this time the one that the Dalai Lama couldn’t answer: “How can we reconcile the technology of cloning with the belief in reincarnation?”

This was ChatGPT’s response:

CLONING AND REINCARNATION ARE SUBJECTS WITH DIFFERENT APPROACHES AND FOUNDATIONS. CLONING REFERS TO THE PROCESS OF CREATING A GENETICALLY IDENTICAL ORGANISM TO ANOTHER THROUGH TECHNIQUES IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY, WHILE REINCARNATION IS A SPIRITUAL BELIEF THAT SUGGESTS THE SOUL OR SPIRIT OF A LIVING BEING CAN CONTINUE TO EXIST AFTER DEATH IN ANOTHER BODY OR FORM. IT IS DIFFICULT TO RECONCILE THESE TWO SUBJECTS AS THEY HAVE DIFFERENT SCIENTIFIC AND PHILOSOPHICAL FOUNDATIONS.

If you ask the same question to a search engine like Google, the result is a link to the National Human Genome Research Institute. Thus, ChatGPT’s response represents a quantum leap. Yet, it is as predictable as it is dull. It took me over 20 years to realize that the answer from the successor of tulkus, the reincarnation of Avalokiteśvara, was the correct one. True, my question did not make much sense; it is almost a joke, a poetic gesture, just like the question about a clown defining a contract or a lava lamp catching a shark. These are not questions to be answered; they are questions to be heard. That is why the best response is “I don’t know. Give me some time to think about it.”

Prediction markets forecast that in just three short years, an artificial intelligence program will be able to pass the laughter test (i.e., watch an episode of Seinfeld and laugh at the appropriate moments); in about five years, it will be able to pass the Turing test (i.e., successfully simulate human intelligence); and in about 20 years, it will not only simulate it but manifest it in an ostensible manner. The capabilities of ChatGPT in 2023 are astonishing, but there are still many things it doesn’t know. Ask it, and it will provide you with a complete list. We know that ChatGPT, as its name implies, can chat, but it lacks the ability to remain silent. Therefore, the epistemological humility of the Dalai Lama offers an alternative criterion for evaluating the future. We can claim to have achieved a revolution in artificial intelligence only when one of these shiny tools responds to a question with poetic overtones with a simple “I don’t know. Give me some time to think about it.”

Pablo, you are out of control and I would not have it any other way. Take care of your heart in these dark times.