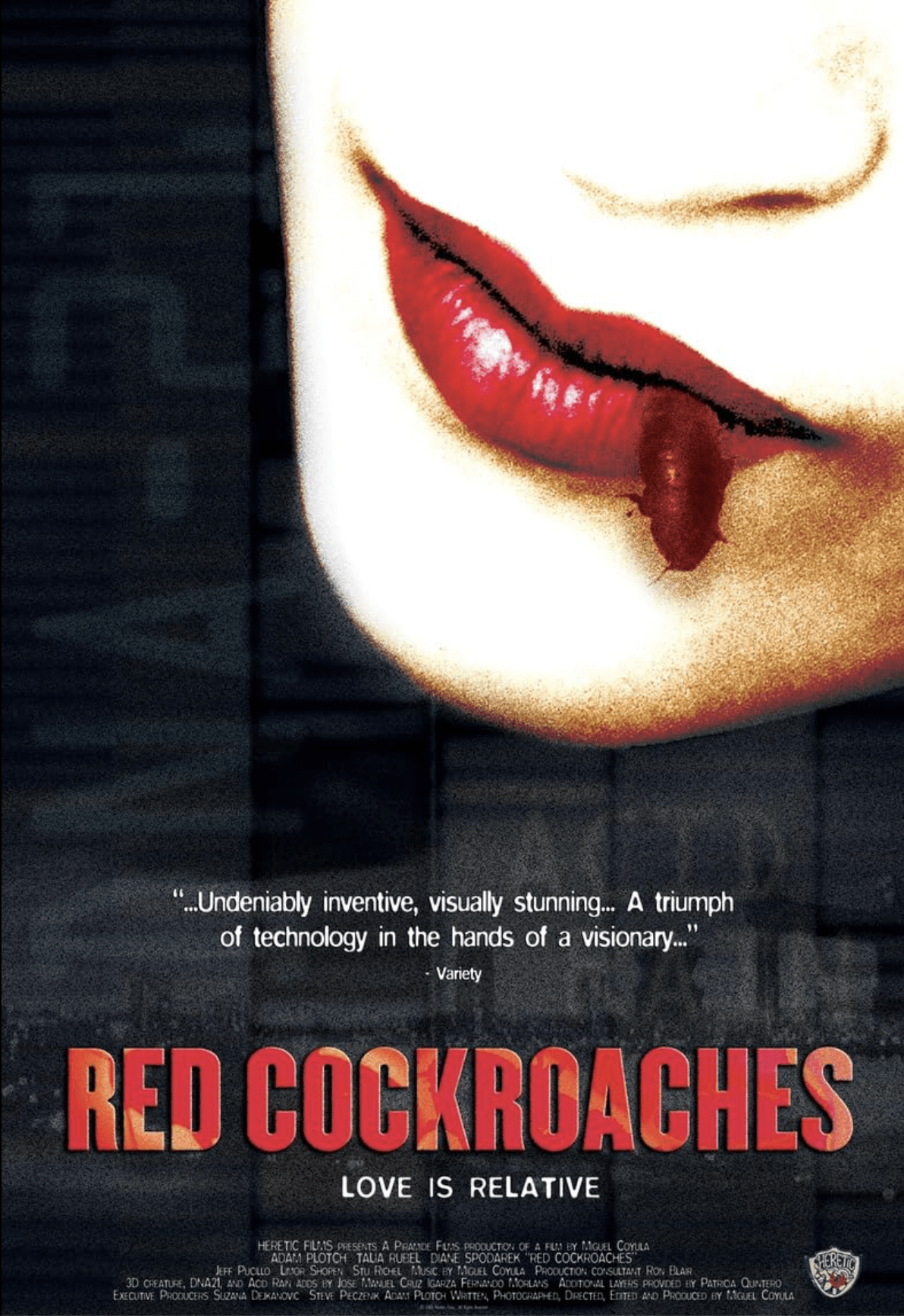

What Miguel Coyula did for independent Cuban cinema has yet to be fully understood. Perhaps that’s why the special Blu-Ray edition of his debut film, Red Cockroaches (2003), has just been released in the United States by Saturn’s Core Audio & Video, OCN Distribution, and Vinegar Syndrome.

This edition revisits a feature film considered paradigmatic within the so-called microcinema production scene. The term aimed to encompass the primitive period of digital film production, marked by a true explosion of low-budget films edited on personal computers and distributed through festivals or on video tapes, discs, and the Internet.

Red Cockroaches already had commercial distribution in 2005, thanks to Heretic Films. However, this new edition includes extra material, both new and archival, the option of director commentary, and some of Coyula’s short films. Its second life underscores the heroism of making a feature with two thousand dollars and a Canon GL1 camera by a Cuban filmmaker living in the United States, daring to delve into science fiction and explore challenging themes like incest and genetic manipulation, with a style associated with David Lynch, Ridley Scott, and Alejandro Jodorowsky.

From the perspective of film studies, revisiting Red Cockroaches allows us to witness Coyula’s evolution as a filmmaker with a unique personality within Cuban cinematic culture. He has been a pioneer in many ways, steadfastly maintaining the radical nature of his cinematic vision despite the obstacles he has faced.

While Red Cockroaches shares stylistic elements with Coyula’s earlier works, especially The Plastic Fork (2001), it might be easier to understand in 2021, following the release of Blue Heart. This is because both films draw from the same narrative universe: Coyula’s novel Mar Rojo, Mal Azul, written in 1999 and published in 2013. Everything is already there: the dystopian framework of the story, genetic manipulation of humans by the dark corporate machinery known as DNA21, the mutant beings generated by such experiments, and the protagonists’ rebellion against an unbearable moral order. These elements, which seemed millenarian around 2003, ended up becoming the focal point of Coyula’s recurring questions.

However, when I asked the director for his impressions on the film he now views with a twenty-year distance, I found that his concerns back then were more akin to those facing a rite of passage.

“For my first feature film, I wanted to tell a slightly more linear story than in The Plastic Fork,” says Coyula. “That’s why my filming of it adhered more to traditional production and shooting timelines. I started filming in 2001, after receiving a scholarship at the Lee Strasberg Institute in New York. I wrote the script during the scholarship; filming took a year, followed by editing. I didn’t do what I usually did, having an idea while editing and going out to shoot it.”

Actor Adam Plotch, the protagonist of Red Cockroaches, had previously worked with Coyula on The Plastic Fork, which was shot in just two weeks.

“The main location was the actor’s own house, and the character was also named Adam. Much of the film happened there, although we also got into his car and went out to find locations. He had studied at NYU Tisch School of the Arts. We put an ad in ‘Backstage’ magazine to choose the actress. About 300 actresses auditioned, and Talia Rubel stood out, with a face that I found very interesting. For me, she is the film’s greatest discovery. She has a very angular face, like a Modigliani painting, offering a quality that feels otherworldly.”

Coyula recalls the challenges of filming during the prehistory of digital cinematography: cameras were not yet high definition, recorded on miniDV cassettes, and lighting was always complicated. However, there are traits he developed then that he still maintains today: “It was done without asking for permission. I haven’t changed my way of working from my early shorts in Havana to Blue Heart, my latest film: guerrilla filmmaking, with a maximum of two people behind the camera.”

“I dedicated more time to digital image processing in this film,” Coyula explains, “because when filming without permission, you don’t have physical control over locations, and sometimes there were elements in the background that didn’t interest you or others missing that you had to add digitally. The same happened with colors since colors were very important to this film. Therefore, a significant part of color manipulation was done digitally.”

In this film, Coyula didn’t aim to use digital media to make the visual result resemble photochemical images but to take advantage of its specificities. “I’ve always thought that the big problem in those years with digital was that many people tried to make the image look like film, but they didn’t exploit the possibilities at the level of image, editing, and structure that the format offered. It was a revolution for independent filmmakers everywhere. It allowed them, in Cuba, to break free from ICAIC, for example.”

Red Cockroaches also possesses that unique quality of Coyula’s cinema, where he never repeats shots during shooting. “I start from the principle that, in literature, when you write a sentence and put a period, another sentence begins, which is a different image when translated into audiovisual language. This made the process more complicated because, for a scene, we usually had to make many more shots than for traditional coverage. I start with the idea that each moment of the scene has the ideal frame to tell it, to create a certain discomfort, which is something I like in cinema, that it is somehow uncomfortable, even if the genre is not suspense or thriller.”

However, twenty years later, Miguel Coyula allows himself to be critical of his debut film, beyond the praise it still receives. “At this point, I’m not too interested; I find it too linear. I don’t like the resolution of many scenes, where it’s obvious that narrative elements are communicated through dialogue. What I still like is the editing, especially the transitions between scenes; I’ve always started from the idea that the transition can create an extra meaning of connection between scenes, provoking discomfort. The transition, for me, must disorient the viewer; it’s like self-sabotage where you disrupt the rhythm you were maintaining to avoid getting used to the same style or a specific pace.”

“Despite considering it the least successful of my films, paradoxically, it’s the only one that has achieved commercial distribution,” reflects Coyula. “Which says a lot about the state of current cinema. One would think that my later films, which I consider better, would have had minimal commercial release. But it also happens that Red Cockroaches is filmed in English and doesn’t require a too specific context or knowledge of the history or culture of a country other than the United States to understand it. Both times it has been distributed, perhaps, it retains an audience. At the time, it moved quite a bit through festivals, and won many awards. And that surprised me because I had made it as an exercise to overcome the fear of making a feature film, as it was later with Memories of Development.”