“Tiempos Abstractos” (“Abstract Times”) is, first and foremost, a bi-personal exhibition. It is a constructed sentence that revisits and investigates moments of the national cultural history seen from and based on Geometric Abstraction, built on a pair of independent trajectories that at times intertwine in strategic segments placed by the exhibition for public consideration.

Broadly speaking, the project was the realization of an idea that had been ruminated upon for almost a decade, consistently sharpened in the dialogues between José Ángel Rosabal (1935) and José Ángel Vincench (1973), supported by the mediation and coordination of Rafael DiazCasas. A possibility stretched out by various inclemencies until it was anchored both on purpose, at the 15th Havana Biennial, and randomly, at the Centro Hispanoamericano de Cultura. By chance, it arose from a casual encounter; it was solidified later, when we presented the project as a fixed proposal of the Centro for the Biennial. A path that, although not free of obstacles, left an excellent flavor when it materialized last November 15. In the end, space and project seemed to be irremediably destined: the gallery management, vigilantly watching over the question of adaptability, fitted everything to the measurement in terms of positioning and dialogue, even going so far as to make the challenges of the space work in the exhibition’s favor. But beyond visual suitability, the exhibition acquires a symbolic weight in the current artistic context, for expressing via an abstract language social concern using a voice and tone reflective of the Cuban scenario of the 1950s, to which Rosabal was directly linked.

Tiempos Abstractos: Rosabal & Vincench takes place in a Biennial—just like the last one— questionable in its raison d’être, overshadowed by uncertainties and sharpened conflicts in the political-social field that affect the entire Cuban reality. An environment of galloping inflation, an expression of economic collapse, which, together with limitations to civil liberties, has generated the largest migratory wave in the country’s history. This situation is replicated in the creative field and, naturally, disrupts the normal processes of the artistic work and even hinders the act of creating. Despite this, both artists decided to give free rein to the project, throwing fuel upon and reinforcing the interest of a not-so-attractive inaugural panorama: characterized by the absence of the former fanfare of great festivity, of colossal projects, the nonexistence of relevant national and international figures and the lack of the usual popular celebration.

During the gestation of the proposal, and before our paths crossed, Rosabal and Vincench had avoided conservative stances and views, for non-artistic reasons, thus tuning the symbolic flow of the project with the abstract times that beset us. In essence, the exhibition’s intent comes to be determined as a modest gesture, an effort to oxygenate the insular panorama of the visual arts by means of presence and promotion – leaving aside several other things.

And, logically, it is worth emphasizing the return of Rosabal’s work. A product of his time, his decision to go into exile functioned as the rational means to nurture personal and creative urgencies, which were limited in an environment that had consciously closed itself to ecstatic awareness with the epic glory of the early years of the Revolution. It was not until 2015 that, collaborating with Juanito Delgado and his project Detrás del muro, Rosabal returned to Cuba and presented a work with almost half a century’s journey. The young man who left Cuba in 1968 returned with the cachet of a career that was introduced to younger generations. Paradoxically, the return of 2024 is loaded with sensations similar to those of 2015. In fact, it would seem an even more unusual scenario given the specific complications of the moment, giving his presence and taking into account his artistic and personal history, the ability to increase to some extent the value and significance of the project. To this we can add Vincench, who—although younger—has set unique guidelines in the audacious handling of the abstract sign as a conceptual element of reflection and resistance, resulting in a combination capable of managing from abstraction a particular debate of necessary attention for Cuban artistic history.

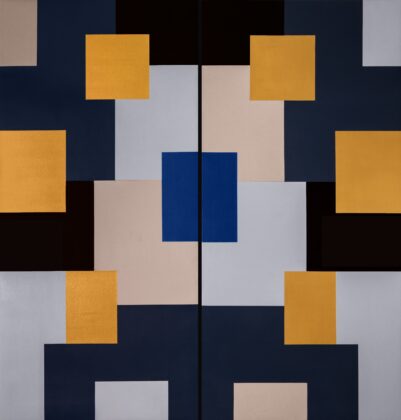

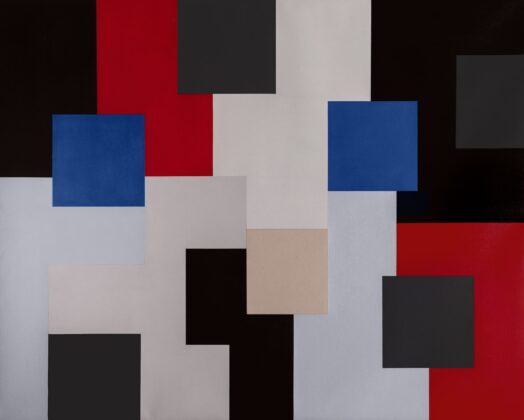

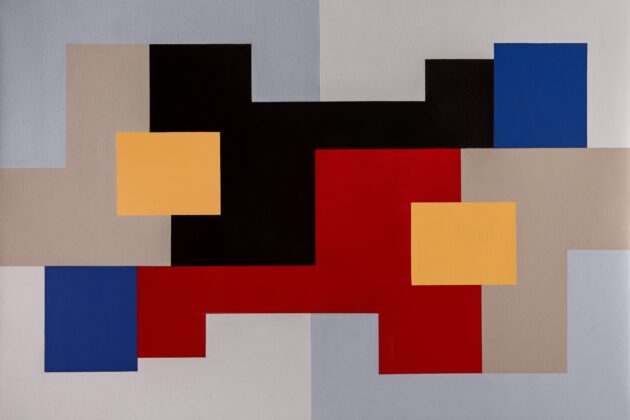

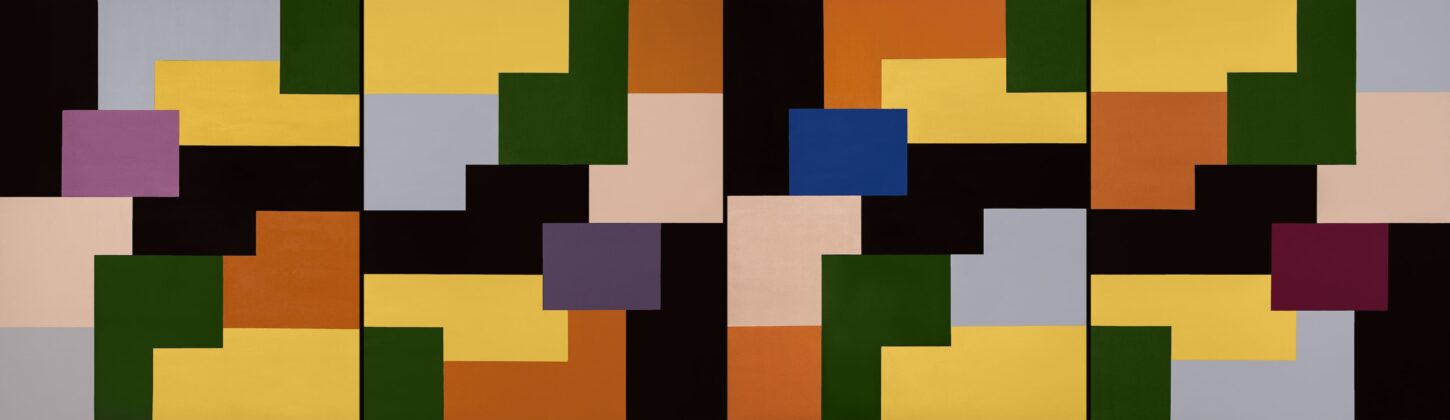

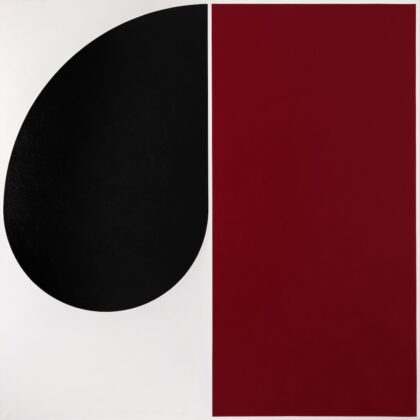

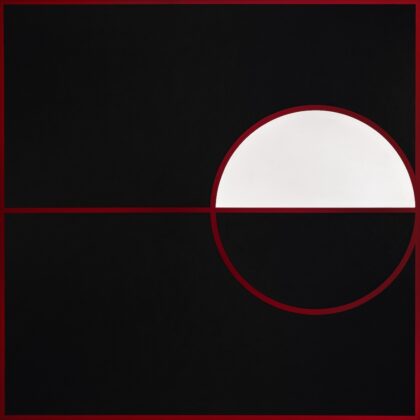

In essence, the dialogue in “Tiempos Abstractos” seems to be oriented toward a possible friction generated between two avenues of concretism, which is the path and the original visual nexus of the conversation. Rosabal with his interplay of forms moves in the spectrum conceived by the theory of color, engaged in analogous and contrasting procedures associated with the visual action per se. Whereas Vincench uses abstraction as a means and instrument to fragment a very specific referent, a concept behind the forms of the written word, an execution that is discovered in each painting as a critical fragment towards a much broader horizon, a “social” text. Both procedures result in pieces connected and intertwined by their formal construction, giving themselves the pleasure of proving independent kinship to the method. Nevertheless, in both, the intention branches out towards the insular reality, unfolding in a procedure that annuls any hint of evasion. The intention in the use of color and the titles of Rosabal’s paintings, and the intrinsic critical sentence in Vincench’s, are reinforced in the exhibition’s own double meaning, which is both its attribute and proclamation. Rather than generating passionate and heated debates, “Tiempos Abstractos” reaffirms with incisive serenity on the possibilities of visual research that abstraction is capable of enhancing on the context, by calibrating itself directly and indirectly as a visual-linguistic tool, undoubtedly a subtext that amplifies its impact.

In the tsunami of circumstances that mark current events, and particularly within the 15th Havana Bienal, “Tiempos Abstractos” is a crucial exhibition, not only because of the duo that makes it up, Rosabal and Vincench, but also for its sharp and discordant voice in the official scramble. To which is added the audacious command of abstract language in the public sphere as a dynamic instrument of social commentary. Thus, diluted in the waters of the Malecón and escorted by the centuries-old mythical caryatids of Havana, this proposal will be remembered as an exercise in modulation to pair up – without losing individual marks – forceful voices in the pictorial field.

Unquestionably within the horizons built around abstraction, and in the island’s visual arts historiography, the narrative of “Tiempos Abstractos: Rosabal & Vincench” without doubt earns a place as a milestone and testament to its circumstances.

* This text is a version of the catalog of the exhibition “Abstract Times: Rosabal & Vincench”, which can be seen partially at the Buena Vista Vincench Studio (Street 78 #1526 esq. 15, Playa, Havana) until February 28th, 2025.

A great honor been part of this exhibit as the photographer ☺️