With his new graphic memoir, Worm: A Cuban American Odyssey, artist, activist, and proud “gusano-americano” Edel Rodríguez declares: “I grew up in a dictatorship and I don’t want the same thing to happen in the United States,” making clear his rejection of the populist authoritarianism of both Fidel Castro and Donald Trump.

Six months ago, in the late spring of 2023, I went to the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, Queens to see the New York premiere of the documentary The Padilla Affair by Cuban director Pavel Giroud. Afterward, Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo, my old comrade-in-arms from the heyday of the Cuban blogosphere, informed me that Edel Rodríguez, the graphic artist who had designed the official poster for the film, was “in the house” and introduced me to him along with his American wife Jennifer Roth.

For several years I had developed a growing interest in Rodríguez’s original, eloquent, and unapologetically political graphic artwork, especially given his open criticism on social media first of the candidacy and then of the presidency of Donald Trump. Rodríguez has described the particular challenge that making such provocative political art entails for him, saying to The New York Times’ Benjamin P. Russell, “The hardest thing about making political art isn’t technique but judgment: knowing just where to stick the ‘tip of the knife’ so that audiences feel provoked without crying foul.”

My interest in and curiosity about Rodríguez’s work only grew when I discovered that he was Cuban. “¡Cubano!” I thought, “¿Cómo puede ser?”

Given what many Cuban-Americans experienced under Fidel Castro’s populist authoritarian Communist dictatorship before fleeing to the U.S., I had initially thought they would be among the first canaries in the coal mine to sound the alarm about the threat “trumpismo” represented for American democracy. I was wrong, of course. Indeed, Cuban-Americans tend to be among the most loyal and vociferous parts of the MAGA base, a fact illustrated most recently by Trump’s holding of a massive rally on the evening of November 8, 2023 in Hialeah, Miami’s premier Cuban-American enclave in lieu of attending the second Republican primary debate that same night.

“Just like the Cuban regime,” Trump assured his supporters that night, “the Biden administration is trying to put their political opponents in jail, shutting down free speech, taking bribes and kickbacks to enrich themselves and their very spoiled children.” Given their direct personal experience of the anti-democratic behavior of the Cuban regime, one might suppose that Trump’s Cuban-American fans might see through this manipulative rhetoric and recognize that it is Trump himself who has most closely followed the authoritarian playbook while in office – seeking as he did to erode U.S. democratic institutions and overturn a legitimate election.

However, Rodríguez has been a bit of a voice in the Cuban-American wilderness when it comes to Trump’s authoritarianism even though he assures me in our interview below that many of his fellow exiles share his concerns. It’s just that the media (and pundits like me) always emphasize the supposedly monolithically conservative and even reactionary character of the Cuban diaspora!

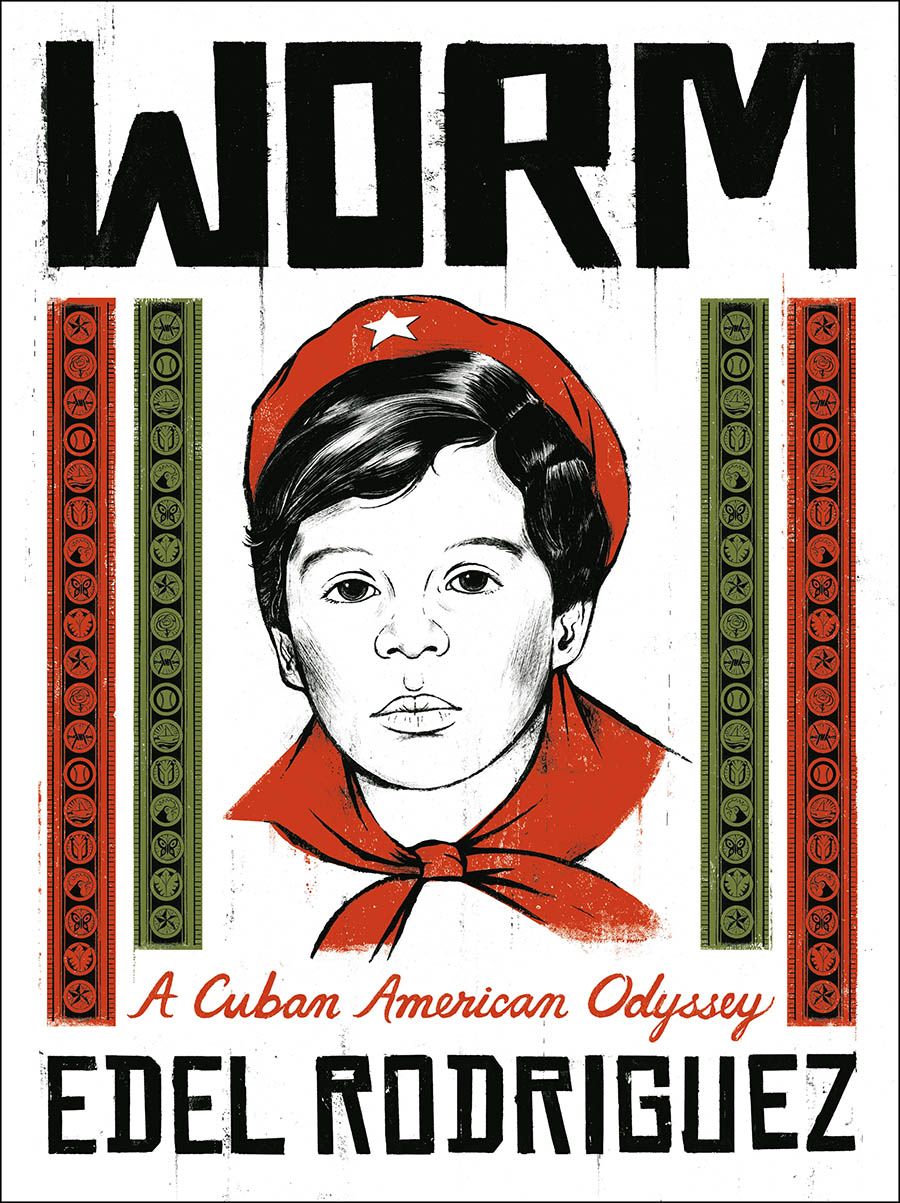

Then, I discovered that Rodríguez was about to publish a graphic memoir contrasting his childhood as a “pioneer” in Cuba with his transformation into a “worm” by Castro’s propaganda machine. Reading an advance copy of his book back in June, I was amazed at how in his telling, this story (the first half of which takes place in Cuba) comes full circle and connects his traumatic history there (from “pioneer,” to “worm,” to “marielito”) with his new life in the United States as an American, artist, and activist.

As we learn in the early chapters of his memoir, Rodríguez was born in the far southern outskirts of Havana in a tiny sugar town named El Gabriel which is itself located 10 miles south-southeast of San Antonio de los Baños. In fact, the artist’s birth in 1971 coincided that the same year with the Oscar-worthy self-critical performance of the poet Heberto Padilla as portrayed in Giroud’s essential film. However, as Rodríguez narrates with a wealth of detailed drawings and a color palette intentionally limited to the revolutionary red, black, olive green of his youth (and – towards the end of the book– Trump’s insurrectionist yellow and orange), when he was only eight years old he fled Cuba with his family as one of the more than 125,000 refugees who left the island during the Mariel boatlift.

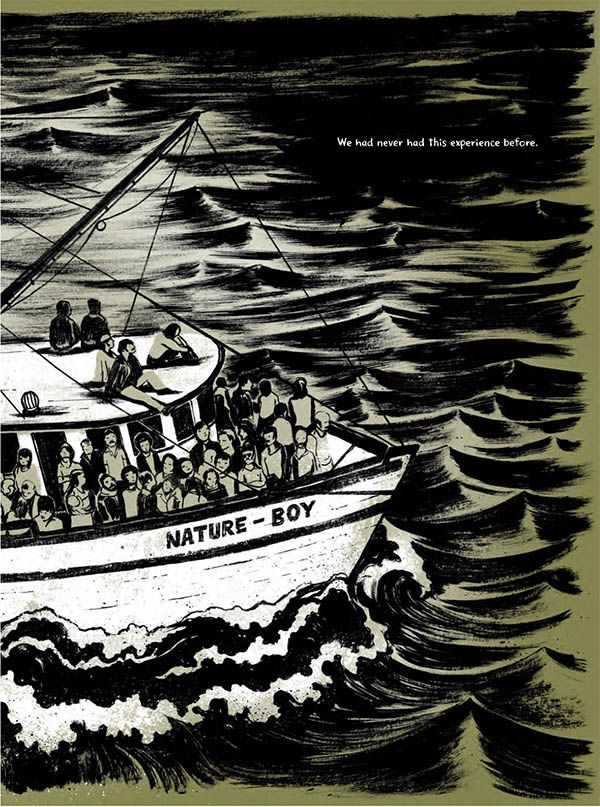

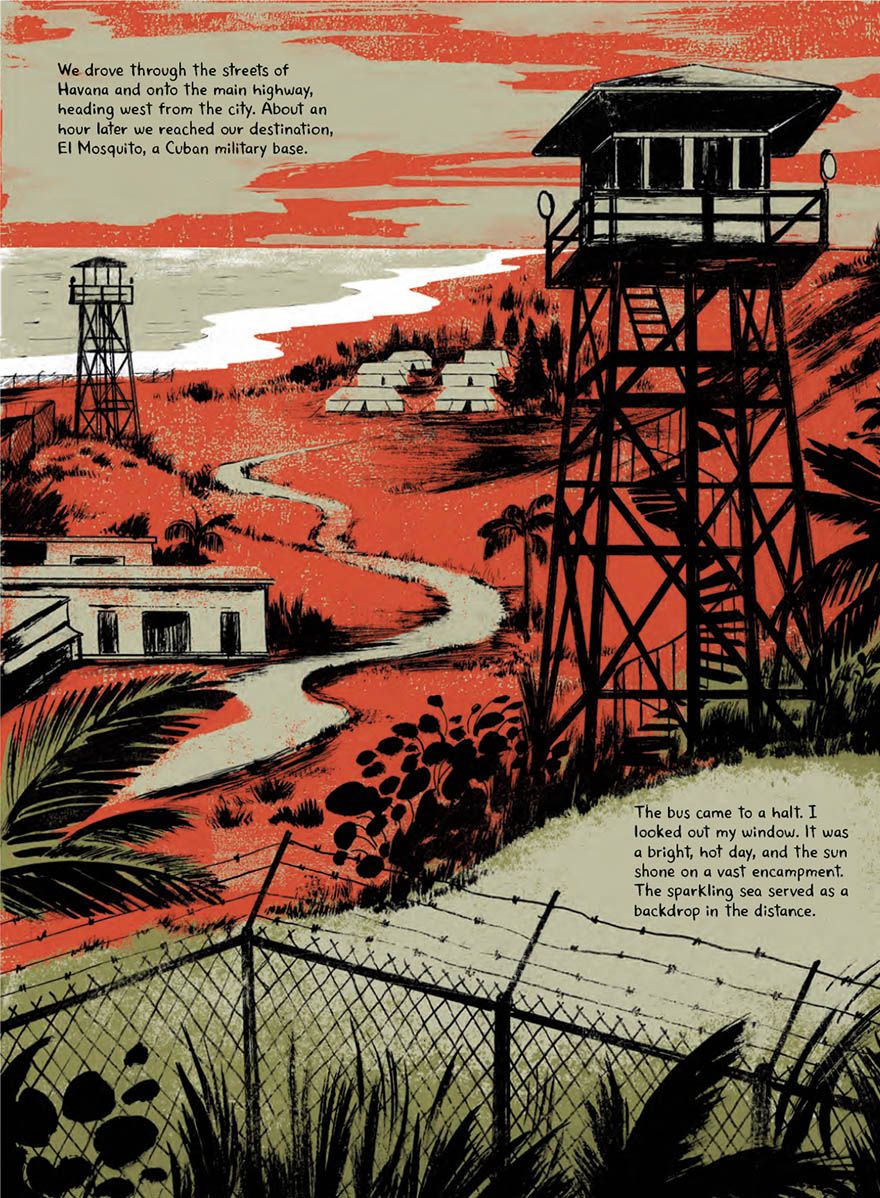

Although Rodríguez was educated by the Cuban socialist system to “be like Che,” that is, as “a pioneer for communism,” the first part of his book recounts how his parents’ growing rejection of the lack of basic freedoms and the possibility for a decent future for their children gradually turned them all into counterrevolutionary “worms.” After enduring a true Via Crucis in a temporary refugee camp named “El Mosquito” at the port of Mariel in the summer of 1980 while waiting more than a week to leave Cuba, Rodríguez and his extended family were finally able to make a chilling sea crossing on the fishing boat “Nature Boy” and reach the United States. Ironically, Rodríguez was able to happily leave behind the “pioneer” and “worm” labels of his childhood in Cuba only to be rechristened “ref” (refugee) by his North American classmates at his Miami elementary school since they were fed up with the arrival of penniless new immigrants.

This personal and family odyssey that turned Rodríguez and his family into proud “gusanos-americanos” (thus the ironic strategy of selecting “Worm” as the book’s title) is followed in the second part of the book by another pair of odysseys, now professional and political. That is, although his parents sacrificed everything to give him and his older sister new opportunities in a free and democratic country, Rodríguez decides that he has to leave his parents behind in Hialeah to go to New York in order to achieve his professional goals and ambitions as artist.

Rodríguez’s third odyssey is political. Although since his teens his art and politics had always tended toward the “progressive” side of the political spectrum (in the ‘80s he became a fan of decidedly political bands like Public Enemy, Rage Against the Machine, Metallica, and U2), he only became well-known and controversial beyond the insular world of graphic art in 2016.

As recounted in two of the final chapters of the book, “Enemy of the People” and “The Big Lie,” it was during the presidential primaries that spring that Rodríguez began to use his talent as an artist to criticize the increasingly clear and dangerous authoritarian behavior of Donald Trump. “One Republican candidate,” he writes, “stood out as dangerous [since] many things about him reminded me of a totalitarian.”

His fear-mongering, his constant attacks on his “enemies” (the press, women, and ethnic and racial minorities), and his encouragement of political violence, all made Trump resemble Fidel Castro in the eyes (and drawings) of Rodríguez. “Listening to him,” Rodríguez writes, “reminded me of the dictator my family had fled.” Furthermore, upon witnessing the massive gatherings of Trump’s delirious followers, he could not help but remember the enraged masses and acts of repudiation that Castro encouraged against the so-called “scum,” “worms,” and “enemies of the homeland” in the Cuba of his childhood.

As a refugee from a totalitarian (and communist) dictatorship, Rodríguez thought he had a valuable perspective that would allow him to credibly sound the alarm about the danger this “orange menace” posed to American democracy. So, he decided to begin flooding social media with his uniquely penetrating images of Trump, making a daily mockery of the candidate’s stream of astonishing neo-fascist statements. “I came to think of my laptop as a kind of printing press,” he recalls in the book. “I was my own editor and publisher and I didn’t have to seek anyone’s permission or approval.”

As his drawings proved as impactful as they were viral and ubiquitous, Rodríguez quickly gained traction in the mainstream media together with praise from the American left and criticism from the right – including threats from the now empowered and shameless Trumpian fringe. With his public profile now growing, some of the most popular magazines in the world such as Time (USA) and Der Spiegel (Germany) hired him to design their covers with his provocative images about the threat that Trump’s rise represented for American democracy.

Like many who saw Trump’s possible re-election in 2020 as the beginning of the end of American democracy, Rodríguez celebrated Joseph Biden’s electoral victory that November. However, the violent attack against the peaceful transfer of executive power that occurred on January 6, 2021 gave him a tremendous shock because it shattered the belief that existed for more than two centuries in his country of refuge as an exemplary democracy, guide, and beacon for the world.

In his book, these final scenes that play out on the steps of Washington DC’s Capitol Building on January 6, 2021 are portrayed with a chilling power intentionally reminiscent of the early days of the Cuban insurrection of 1959. “The failure to safeguard democracy puts it in danger, and at a certain point one forgets what it is. One loses the knowledge of liberty,” Rodríguez concludes.

Implicitly, Rodríguez is asking his readers: “This is what happened in Cuba; Can the same thing happen in the U.S.?”

After arriving in the United States as a refugee in 1980 and gradually becoming an American over the next 40 years, Rodríguez came to believe that the dream of a democratic country with opportunities for dignified work and the freedom to publicly express one’s own opinions without fear could be a reality. So, to him, the attack on the Capitol –incredibly egged on by President Trump himself in a U.S. version of the all-too-common Latin American “autogolpe”– seemed like the death of a close family member; evidence of the growth within the American body politic of the same blind nationalism and cancerous cult of personality that destroyed his native country.

In the end, Rodríguez’s book is a mirror. It shows an America that the artist did not recognize or know could even exist in the same place that offered him and his entire family a promise of refuge, security, and a new beginning as freedom-seeking immigrants. But by telling the two parts of his coming-of-age odyssey –both the Cuban and the American– together, and employing his talent as an artist and his resistance as an activist, Rodríguez ends up defending the democratic, anti-authoritarian values that all Americans should share, beyond left and right.

Although your book is a graphic memoir of the 50 years of life you have lived between Cuba and the United States, it also tells the story of your father, Cesareo “Tato” Rodríguez. Who is he and how did he turn out – together with you – to be the main protagonist of your book?

My father was born in 1938 and experienced the most shocking events on the island over the next 42 years. This included the Batista years, the sabotage attacks during the 1950s, the Revolution, the Cuban missile crisis, the U.S. embargo, the 1970s, and of course Mariel. He is like a walking encyclopedia of Cuban history and has told me stories about all these events since I was a child. When I had my own daughters, I started thinking a little more like him. What would I have done if I were in his place when he had to make the decision to leave the country? When I was writing the book, I got the idea of portraying our relationship. My dad is a tremendous character so I wanted to put him more at the center of the story.

During the process of writing and drawing the book, how much of the content was based on your personal memories of childhood and how much is the result of interviews you did with your family?

The book is a combination of personal memoir and research. I had my own memories and point of view, especially when it came to the images and places I portray, but there were many other points of view which I wanted to include in the book, such as logistics, politics, things that were happening behind the curtain, and things that my parents didn’t want to tell me to protect me as a child. We talked about some of those things after we arrived in the U.S. as refugees, but I discovered more of them during the interviews I did with my family.

Although your book is a graphic memoir that prioritizes your art, it is also a written text that chronicles many key events in your life. What was the process of producing the book like especially in terms of writing a story vs. drawing that same story?

I wrote the text of the book first. It has about 60,000 words. Then I started editing and deciding which details were going to go with the images and which would remain as a separate text. I wanted to create a book that had more textual detail and information than the typical graphic novel. I wanted to produce a book in which each page grabs you and makes you pay attention.

Could you describe the process of transforming a specific idea or story into an image for the book? For example, there are the chilling images in the four chapters that show the violence you and your family endured during the Mariel exodus: “Farewell,” “El Mosquito” (the detention camp), “The Wait,” and “Nature Boy” (the name of the shrimping ship your family traveled on coming from Cuba to the United States).

These are events I have had in my mind since they occurred when I was just 8 years old, which I have drawn on other occasions. Sometimes my mother asks me: “How do you remember that?” Parents think that children are not paying attention to things, but many children remember everything, especially traumatic things like leaving their grandparents behind in another country or spending time in a detention camp. Those are things that one never forgets. I remember the spaces, the angles from which I saw a situation, and even the light in a particular moment. Once I have all those details in my memory, in my mind, I start to draw and everything comes out naturally because I know it and I feel it.

Why did you decide to title your book WORM? What is a “worm” in the Cuban context?

I have been interested in the word “worm” since I first heard it used against people when I was a child. It is the mocking name that Castro and the members of the Communist Party gave to people who were dissatisfied with the Revolution. It was used as an insult in those times. Over time, I have learned that similarly degrading words have been used by dictatorial regimes throughout history. The Nazis called Jews “rats” and the word “cockroach” was used against the Tutsi ethnic minority during the Rwandan genocide.

Since I was a child, I have asked myself, “why do they call me ‘worm’?” What have I done to deserve that? I was a Cuban child just like any other, why this “worm” thing? Reflecting on this gave me the idea of drawing my portrait dressed as a pioneer with the word “WORM” in capital letters above it. I like the juxtaposition. I think it says it all. Many who have left Cuba proudly declare themselves to be “worms.”

The parts of your book that show Cuba do not focus on all of Cuba or even on its capital city Havana very much. Instead, we are shown the specific places where you grew up. Why did you decide to place such emphasis on your hometown “El Gabriel” and what special influence did this small sugar town have on your formation?

For me, El Gabriel was the whole world. It is a town of people who help each other, hard-working and honest people, but very poor. It’s exactly the kind of place the Revolution said it wanted to help from the beginning, but never did. El Gabriel is like an island, far from other towns, so it had to survive in its own way because help never arrived. It is an island within another island, which is Cuba. It’s where I learned to draw, to make toys with my own hands, to hunt birds, and fight with my little friends in the street. I have many memories of my hometown and I wanted to share those moments with readers, so they would understand how difficult it was for me to leave that town behind.

One of my favorite parts of the book is chapter 7, “The Kitchen.” The main character is a dead contraband pig. What message did you want to communicate with such a chapter?

That kind of experience is something that doesn’t exist in many other places. Typically, people outside of Cuba go to the market with their earnings and buy what they need. In Cuba, people spend the day “luchando” (struggling) in that kind of thing, searching, asking where there is food, standing in lines, and negotiating. I wanted to give an example of what is typical in Cuba so that readers would understand the daily frustrations that motivated us to seek out a new life somewhere else, outside of Cuba.

Perhaps every book about Cuba has to have a chapter titled “Chevrolet.” But the focus of your chapter is not the American car itself, but rather particular and very creative uses of the car. What was your father’s Chevy used for?

I loved my father’s car, a red and white 1951 Chevrolet. He took me on many trips with it along the roads of our town and through the surrounding cane fields. Later I discovered that this car was the place where my parents discussed what was happening in the country and where they decided to leave. Such conversations were very difficult to have at home because the neighbors might hear them, so the car was the only safe, private place where they could talk.

Furthermore, my father sometimes worked as a cabbie, giving rides to passengers between the countryside and Havana. In fact, he was on one of these trips when he learned about the first events that led to the Mariel boatlift, the events at the Peruvian Embassy. So many important things happened in this car that I decided to give it its own chapter.

The main journey portrayed in your book is the sea voyage between Cuba (Mariel) and the U.S. (Miami) that ended up turning you into a refugee and a (Cuban) American. However, later you decided to leave Miami and study art in New York, a trip that turned you into an artist. Looking back at this decision (which made your mother very unhappy at the time) now more than 30 years later, how did it change the trajectory of your life?

Opportunities for artists in Miami back then were few, that’s why I decided to study in New York. It was difficult for my parents because they wanted me close to them, but I wanted to take advantage of all the promise of this new country. The trajectory of my life changed completely. I studied art with some of the best teachers in the city and met many people who helped me thrive in the art world, things that could not have happened in Miami. The center of art as well as magazine and book publishing was New York and I took advantage of every opportunity.

You are a “Triple A”: a (Cuban) American, an artist, and an activist. Can you remember a time when you practiced art without mixing it with “politics”? That is, without using your art to promote your activism? Why did you decide to become a political activist?

The work I do as a political activist is only one part of what I do in the studio. I also draw and paint on other subjects for exhibitions, write and draw children’s books, and make art for music groups, posters for operas and the theater, and do book covers as well. My political work, my “activist art,” you might say, is what often gets the most notice because it appears on the covers of magazines and in the news. However, I have worked like that since I was in college in the early-1990s, painting personal subjects and illustrating political topics for the school newspaper. In fact, I think the last time I didn’t mix politics with my art was in elementary school. At some point in the ‘80s I discovered the music of groups like Public Enemy, Rage Against the Machine, Metallica, and others and that, along with my history as a refugee and immigrant, encouraged me to put more of my activism in my work.

Towards the end of your book, you focus on Donald Trump, chronicling your own graphic criticism of his populist, anti-democratic rhetoric and policies. Furthermore, you make a direct connection between Trump’s authoritarian style and that of Fidel Castro and his own imposition of a communist dictatorship in Cuba. Making such a connection and denunciation is not common among Cuban Americans. In what ways are these two figures similar and why don’t other Cuban Americans typically make this connection?

To me, Trump and Castro are similar in many ways: their ways of being, speaking, and denigrating certain people. The words they use: Trump’s “scum” is Castro’s “escoria.” Trump’s insults against the press are also very similar, along with the way they encourage others to commit acts of violence against innocent people who they consider “enemies of the homeland.” I make the connection so that the reader understands where my work as an activist comes from. I grew up in a dictatorship and I don’t want the same thing to happen in the United States.

Some in the Cuban-American community do not see this connection because they are blinded by Trump’s propaganda, by the misogyny, racism, and extremism that he offers them. These are very attractive things to some people, but there are many in the community who see things the way I do. We Cuban-Americans are more diverse than what the media typically portrays.

There is a chapter of your book titled “The Return” where you tell the stories of two return visits you made to Cuba, the first with your sister and father in 1994 (one of the toughest years of the special period), and the second fifteen years later in 2009, now with your American wife and two daughters. What was your impression of Cuba in 1994 compared to the Cuba you left in 1980? How was it different to visit Cuba as “the son of a father” (in 1994) compared to the experience of going there as “the father of two daughters” in 2009?

They were two very different visits and I’m glad you noticed the difference. In 1994, as “the son of a father,” as you say, I felt a certain protection, given that my father was by my side. Returning fourteen years after we had left in 1980, our town had changed a lot, things had become truly disastrous and it was very difficult to find even the simplest things. My friends complained a lot and clued me in on the hard truth of life in Cuba, but as before, they had to do so on the “down low” so no one would rat them out. For the first time, I also noticed a certain “apartheid” growing between Cubans and foreign tourists. Stores where people like me could buy almost any kind of food with dollars were open, but Cuban citizens couldn’t enter them. It was the “special period” and people were very sad and depressed.

When I went back with my daughters in 2014, as a father, I felt much more responsible for their well-being. For the first time, I understood what it’s like to live in Cuba and try to take care of your children when things are so complicated. One night, one of my daughters woke up with stomach pains and I told my family that we needed to take her to the doctor. They said, “What doctor? There is no polyclinic here anymore.” Then I suggested we take the car and drive to one but they reminded me: “There is no car here either.” Fortunately, my daughter got better, but I was left with the memory of that parental anxiety.

Why did you decide to conclude your memoir with the chapter “The Promise,” returning your focus to your father’s life and decisions?

I wanted to end the book on a more personal note, returning to the decision that changed the lives of so many members of my family. I think people don’t really understand the decisions of immigrants, what causes someone to leave their parents, to put their children in dangerous situations, on boats, or take them to the border. Many times, parents find themselves without options. My father’s story reflects many of the immigrant stories that happen today but which we don’t give enough attention to.