The blessing promised at the triumph of Fidel Castro’s Revolution would arrive with the usual delay to the small town of Sabanilla, where the dust of the unpaved roads was waiting to rise as the non-existent vehicles passed by. The order to remove all kinds of propaganda was the first news, in the mouths of those who offered to unscrew the posters of Coca Cola, Aspirin, Texaco, Bacardi… and all the other businesses that would cease to exist in Cuba. Whoever did not drink Ironbeer before ‘59, would never try it, unless they went into exile, as happened with the Cuban-origin beverage itself.

Those who stayed to live the story were stripped of the yellow, white, black and red color of the signs hung on the walls and endured the roar of zinc piling up in the streets. They tumbled over each other, puncturing the lacquered surfaces and scratching the typography.

“What will they do with all these signs?” asked a humble resident of the area.

Silence was, of all possible replies, the only one that favored the possibility of re-using them in the construction of the fence in his yard. He foresaw that the communists would soon seek him out, eager to investigate much more serious matters, and that he ran the risk of being “locked up” because of his political affinity and previous work as a policeman during Batista’s mandate. Preparing the family for his predicted absence was his priority, so he gathered as many signs as he could load into the wheelbarrow he used to work the land and moved them to his property. He hammered out a perimeter a hundred meters long, demarcating his land from his neighbor’s and imprisoning the chickens he was breeding which insisted on escaping him.

His gesture was noble and common, guided by the need to reinvent himself in times of crisis and solve his own dilemma. He even helped the communists to get rid of American propaganda without any effort. He did not know then that he was writing the future of his grandson and forging the unconscious of an artist marked by the decision of his ancestors.

Twelve years later, Ronaldy came to the Navarro-Caudales family. The signs on the fence of his grandfather’s house were still there, blurred by the scourge of the sun, the rains and the weather. They demarcated the perimeter of the child’s comfort zone, the places where he crawled and walked. He ran. Later he would jump the fences in his late teens to escape from his mother. Had her permission been required, he would have been forbidden to go, as she did when she learned of his wanderings in the fort inherited from the Batista government and converted into a school by Castro.

Three years had passed since the teachers and apprentices left to work the land under government orders and abandoned the place. Everything remained as they left it, as if they had planned to return the next day. The thick layers of dust on the floor and the swarm of spider webs between the desks and blackboards were the only evidence of the passage of time.

The front door was open, but no neighbor in the area would have thought of raiding the place. To look for what? To do what? There was nothing there but books and they did not fill the belly, nor repair the house, nor restore hope to those who trusted in ideas of change and began to collect the defeats after twenty years of lies.

The only one who conquered the inhospitable space was Ronaldy, or at least, he never witnessed any competitor who made his visits a routine.

Attracted by the architecture, the possibility of adventure and the mischievousness of enjoying his “misbehavior,” he decided to enter one morning and did not leave until sunset. He ran the halls, posed as a teacher in the classrooms and broke one thing or another, but of all the things he could have done and seen, and of the wide variety of rooms the building housed, the library became his favorite. Despite not being keen on reading, the magic of that place gripped him like nothing else had done until then.

The wooden shelves were on the floor, trampling the unlucky books that fell under their weight without any order. Fiction was mixed with biology and poetry with Marxism-Leninism. Covered with mildew and a stroke of mud, children of the mixture of dust and drizzle that crept in through the broken windows.

Avoiding getting his clothes dirty and being punished, Ronaldy always sat in the same corner, but he would browse a new story on each visit. He could not take books home, after his mother’s insistence to put them back where they belonged.

“They don’t have an owner,” he protested, but the next day he returned them to the shelf. One afternoon he discovered Lorca and could never read anything else. The love of poetry was born there, after the revelation that many things could be expressed in a few words.

“Childhood blossoms,” Ronaldy told me, sitting in his fifties in the dining room of his New York apartment. He had crossed the border from Mexico to Texas eighteen years earlier and left Cuba at twenty-two. He never returned, for fear that it would happen to him as it did to his grandfather, and he would have to pay with his life for his ideals. In the only photo that remains of his grandfather, he looks tired, serious and self-absorbed, even though his wife was smiling at the lens next to him. The only job he could get after the change of government was cleaning the floor of the house of culture of Matanzas and the only place where he was safe was in the courtyard of his house, protected by the printed past advertising Coca Cola.

Ronaldy cried, fertilizing the memory while the restless legs syndrome appeared as a manifestation of his thoughts. He moved to the pulse of anxiety inside an orange, yellow and black paint-stained overalls. The droplets that littered the fabric betrayed the range of colors he would use in his next work. The same tones that exposed the countryside before nightfall.

It was a Saturday at noon, and like every Saturday, he had ready the posters he would paste on the streets of Williamsburg at dawn:

NO HAY QUE ENTENDER NADA

ME BASTA CON SENTIRLO

(There’s nothing to understand, it’s enough for me to feel it)

Helvetic typography set to his style and pulse, on 39×57-inch craft paper, conditioned with varnish to resist acrylic and laid out on the floor, was drying in a corner of his room. The thick roll of paper from which he extracted the pieces he used came to him in the mail after ordering them from a butcher’s website. The same cardboard that could have been stained with blood from wrapping cuts of meat and ended up in the trash would be stained with art to display to the world every Sunday.

The two posters would be moved to the fence of a parking lot on Broadway Avenue and replace the ones from the previous week. He would paste them on top of the existing ones because he insists that his art be ephemeral and materially short-lived.

The text that dies on Sundays could have been a fragment of a poem, a haiku, a Cuban décima or a phrase he heard in the street. All those who talk in front of him know that they are being processed through Ronaldy’s filter of muses, the product of a constant search for the “collective unconscious,” as the artist calls the revelations that society gives him in the form of words. At a party, in the subway, on a bus, his ears are on the lookout for the arrival of popular poetry. The one that has never been written. The one that escapes in common conversations as part of everyday life and is captured in the small notebook that Ronaldy carries with him everywhere.

The first thing he draws are two blank squares, exemplifying the frame and surface of his works. “The text arrives when it arrives” and is part of his “phrase bank,” as he calls the enormous compilation of his treasure of notebooks. The periodic selection is impudently conditioned by his feelings and experiences. There are posters announcing springtime, alluding to the smell of the flowers that slips between the horses’ shoes, while others read: “MANDA A TODOS PARA CASA DE LA PINGA AND CARRY ON” (“TELL EVERYONE TO GO TO HELL AND CARRY ON”).

Hanging on the old fence of the parking lot, the posters are waiting for the neighbors to discover them and offer the homage they deserve. In keeping with our times, a post on Instagram is the most common. Many of them ask themselves who the artist might be.

It has been three years since Ronaldy committed to himself to exhibit his work every week. Always anonymously and without receiving monetary compensation for it. Everything he invests comes out of his own pocket, the money he earns from transporting art pieces from gallery to gallery. He treasures and holds in his hands millions of dollars in the form of paintings and sculptures from collectors and private owners who entrust him to move them, but he insists that this is not the future he longs for his work.

In his view, museums are restricted to the will of those who can afford to visit and have an interest in such activities. Instead, his street art surprises you around a corner in Williamsburg, intercepting and changing the community.

A rebel from a young age, Ronaldy insists that art must go from the street to the gallery, not the other way around. He keeps very few posters, but when he does, he peels away with a knife the wad of old posters welded behind the one he plans to exhibit. The thickness of the work is conditioned by months of compiled phrases, and its display is limited to the kindness of “someone who will give him an opening” in the art world.

Ronaldy speaks with gratitude and enjoyment about the time he spent at the Matanzas Art School studying and recreating all the classics. He painted human figures and watercolor landscapes which worked as a springboard for him to travel to Argentina for an exhibition, a chance he took advantage of to stay there in exile for eleven years, but he did not find himself as an artist in repetition. In Buenos Aires he had the idea of tearing a small poster advertising a private carpentry shop from the wall. He felt the need to make it his own, modify it, and return it to the streets in its new version.

“The day you discover why you are here in the world a second birth occurs,” he told me recalling the events.

From then on, he began to walk the avenues in search of signs that would inspire him. In every place he visited he found a street poster to appropriate and where to leave a message of offering to society. He crossed out common words with fragments of poetry, re-using the original text to change the meaning and usefulness. He painted and wrote over them, vandalizing the banality that accompanies this type of serial printing. The short, precise and sharp text appears undeniably conditioned by the place in the world where it was written and the swirl of emotions that accompany the artist’s private life. Anger, frustration, protest, maladjustment and sadness are themes that appear in moments of crisis. To know his work is to know the human being.

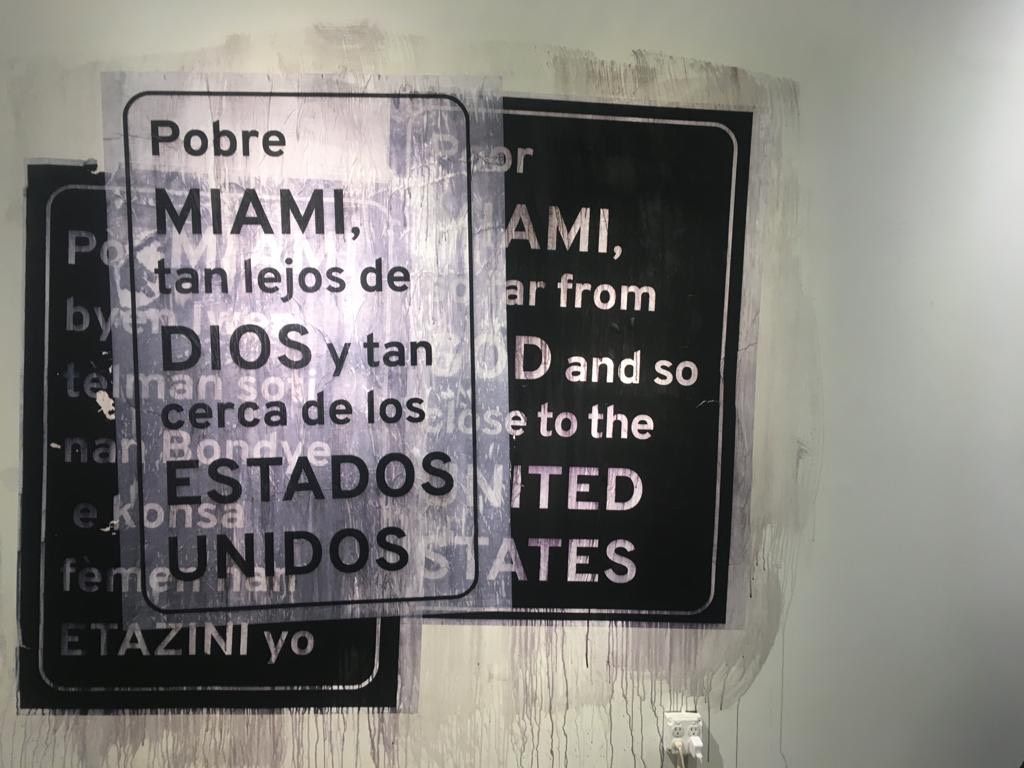

The idea of creating his own posters came to him in Miami, when he discovered that he could use the printer of an architectural company that printed house plans. He had a friend who worked in the office and they made an informal agreement for five black and white posters a week, but the business did not last long and neither did his stay in Miami.

Moving to New York illuminated his artistic path and the confinement in times of pandemic led him to question his creative process. The assistance of technology disappears and the hand-drawn strokes appear, the commitment to deliver a weekly work to the world and the substitution of independent posters for series of two. Colors also appear, coining the text and the decision that each poster must be unique and unrepeatable, as is our history.

Cuba is present in his work and as a tribute he keeps the Spanish language in most of his posters, but he knows that if he had returned to the island, he would not have been able to realize his art. The only printed propaganda in the country belongs to the government and modifying it is a crime. He says he will not return until things change, and with a certain political optimism he talks about putting flowers on the tomb of his ancestors.

The seed of the artist that he is was planted there, in the courtyard of his grandfather’s country house next to the fence of half-blurred American advertising posters and hidden in the abandoned library, where “the power of words blew his mind.”

Contradicting his discourse, Ronaldy speaks very little and even surprised me when he agreed to let me write about him. His work is mostly anonymous and he limits himself to exposing his feelings on his posters. Why expose his face to the light? “Because of my children and for my children,” he told me. “They were both born in free countries far from my reality and I have done my best not to contaminate their path with my personal experiences… but there will come a day when they will ask questions and want to know their father. They need to know where I come from to know what they are.”