Pedro Juan Gutiérrez, at 73, is no longer the sex-addicted alcoholic with sudden fits of rage who in the difficult times of the Special Period was an exemplary specimen of Cuban resilience. Since 2007 he embraced Nichiren Buddhism, a branch of Mahāyāna Buddhism that is based, among other things, on the idea that each person possesses an innate Buddha nature, that is, that we all have the potential to attain enlightenment. But he continues to write; perhaps now with an eye a bit on the past, with the same direct, stark prose that launched him to fame in 1998.

It’s been over two decades since Pedro Juan Gutiérrez took a literary selfie of Havana Center, marginalized, on the verge of collapse, and titled it Trilogía sucia de La Habana (Dirty Havana Trilogy). Today that portrait persists without much change: the same destroyed buildings (now even more dilapidated), overcrowding, and alienation (now with the Internet). Twenty-five years after its publication, he says, Trilogy… could be written again and, broadly speaking, not much would change. Of course, he adds, it should be written by someone else.

To the tourist postcard of the mulatto woman, tobacco, rum, and palm trees, Trilogy… discovered a reverse side of prostitutes, hunger, alcoholism, and overcrowded buildings in danger of collapse. Sadly, that Havana, more real than that of tourists and slogans, is still there, facing the sea, inhabited by several generations of survivors who still, in one way or another, indulge in the post-apocalyptic zeal for life that barely saved them from madness during the early 1990s.

Trilogy… also successfully overcame the fearsome challenge of sex in literature, which is no small thing, especially when heavyweights like Haruki Murakami have been on the shortlist for the Bad Sex in Fiction Award (given since 1993 by Literary Review for the “worst sex scene in an otherwise good novel”) and others like Tom Wolfe have taken home the prize. Pedro Juan Gutiérrez, however, did more than write about sex and not be pathetic in the attempt: he understood its nature in the Cuban context, far removed from certain clichés that still linger internationally, and also the anthropological contradiction that, in extreme moments, makes this closest pleasure an alienating palliative against the blows of misery.

Dirty Havana Trilogy has reaped considerable success internationally; it has been translated into 21 languages. American journalist Richard Bernstein said of the work and its author for The New York Times: “In the brutality of his honesty, Mr. Gutiérrez reminds one of Jean Genêt and Charles Bukowski. He takes us on an unforgettable journey into a world where politics, spiritual anomie, and desire make their troubled accommodation.”

This month marks a quarter of a century since its publication, the perfect excuse to, once again, talk to Pedro Juan Gutiérrez in No Country Magazine.

Pedro Juan, in your stories and novels you develop a very direct style, not at all bombastic, far from the Lezamian vices that one finds quite often in many more or less recent Cuban literary texts. Where does that style come from?

Actually, in my writing, there are no influences from Cuban writers because I began to read, very young, great American storytellers like Sherwood Anderson, Hemingway, Carson McCullers. I was reading, above all, short stories. There was also Guy de Maupassant and Chekhov, who were very important in this sense. But even before this stage, I think the comics that I had been reading since I was seven years old were very influential: Superman, Batman, all that. My aunt was the one who ran the press distributor in the town of San Luis (Pinar del Río), so, when I went there on vacation, I had all those texts at my fingertips, plus the magazine Mecánica Popular and National Geographic. I also have to mention the cinema, which was very important! In Cuba, they stopped showing American films at some point and started showing French and Italian films of that time, the sixties and seventies, which had very different ways of telling stories. But what most influenced my way of writing was reading American storytellers. That was it.

And I suppose also the practice of journalism, which most of the time requires getting to the point.

Journalism was fundamental, above all, to create a work discipline in me. You know that in journalism they tell you that tomorrow you have to deliver four pages before noon, and you have to run and do it quickly, but with quality. It not only helped me with discipline but also taught me to conscientiously do my research before writing the first word. Even if my text had photos in it, I had them already organized before starting to write. I have always been very organized and disciplined. Although it may not seem like it, I am like that. Sometimes I think that in a previous life, I was German.

Regarding the influence on my narrative style, my experiences at the Agencia de Información Nacional (AIN), which today is the Agencia Cubana de Noticias, helped me a lot. There they had writing rules like those of Prensa Latina, which were copied from France-Presse and Reuters, the agencies that invented the rules of cable writing: that if such complements had to be in a certain order, that if the gerund… well, gerunds were forbidden… that if the subordinates in such a way, that if the verb in active voice, that if the verbs were compound. I worked for eight years in the AIN, which was very strict, and that helped me a lot to control the language, to give value to the words. A lot of writers don’t seem to do this and think that writing is about adding words and words and words, and for what they can say in five lines they use two pages. When you do this, the book becomes boring and falls out of your hands because no one can read that. Our language is very excessive, it is extraordinary, and if you don’t have a guide to use it rationally, you get lost in it.

Walter Benjamin said in One Way Street that “The work is the death mask of the draft,” and yes, it is what remains of what the author conceives, but immovable, or almost lifeless; many times, it is far from that idea or first enthusiastic impulse. However, I believe that the work is also the culmination of a process that can be, in principle, a vague idea, somewhat lost, that acquires meaning as it takes shape through language. In this sense, how do you see your creative process?

I’m more of a very slow elaborator of what I’m going to write. I think poems are the only thing that comes to me relatively quickly. When I’m reading something, thinking about something, when someone tells me such and such… bam, a poem comes out. But short stories take more preparation and notes, I have to organize my ideas from here to there, to think very well about the order of events, and a novel, let’s not talk about a novel!

I remember that I spent 21 years thinking and thinking about Fabián and the Chaos, taking notes. And I couldn’t make up my mind, especially for ethical reasons, since it is almost, almost, almost a biography of a great friend of mine. All that time went by between the moment when I realized there was a novel there and when I became able to begin to write it. It was incredible. And I was thinking, taking notes, seeing where I could find an entry point. Writing a novel seems very complicated to me. The idea acquires shape, size, and body as I write, and its strength and energy also increase.

I can’t improvise with these things. Sometimes I’ve been asked to write a story for an anthology, and I tell them: no, I don’t have anything written. And they answer me: but it’s just a story, you can write it in a week. And I say: leave me alone, how can I write a story in a week as if it were a newspaper article? No, it doesn’t work like that.

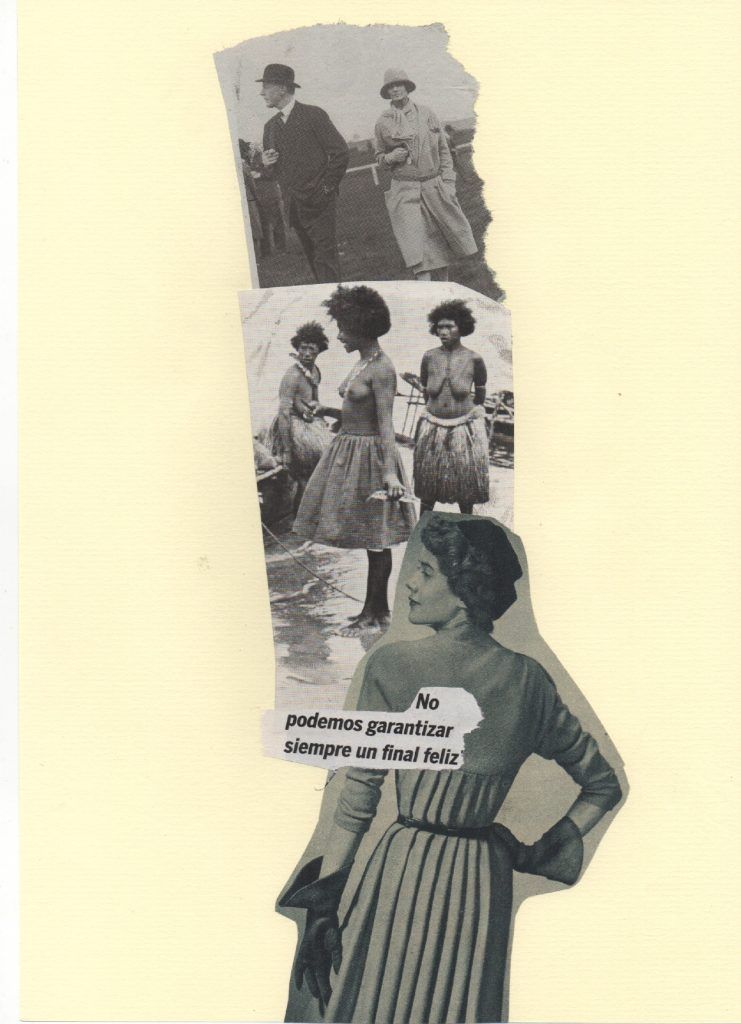

Before I get into your narrative, I’d like to mention your visual poetry. I know that at some point you wanted to study visual arts and could not. However, that need to express yourself through the visual arts has remained. When did you start experimenting with visual poetry? Do you think there are links between it and your narrative?

Well, when I was 16 years old, I had already drawn a lot. I had several notebooks filled with nib drawings, with Indian ink. Then I went to the National School of Art (ENA) and talked to the director. That was in September 1966. When he saw the drawings, he told me: yes, come on Monday, you already have the scholarship. It was as simple as that. But I was enrolled at a technological institute of construction in Rancho Boyeros (Havana), and I was already in the military service. So, I couldn’t enter the ENA. I never studied painting and I took a different road. Then I thought about studying Architecture, but I ended up with a degree in Journalism at the University of Havana. And to journalism I dedicated 26 years of my life.

I started with visual poetry in 1980. I was 30 or 31 years old and I was writing poetry, but one day it occurred to me to take some of my poems, the short ones, and put them on paper, put some little figures on them, and so on, without any intention or artistic aspiration. My wife worked at the bank at the time, she was a secretary and had a photocopier, so I asked her to make photocopies of these poems to send to several friends by mail. Actually, I got into that habit to keep our friendship alive. So, little by little, that took hold of me and I started to make them bigger, in larger formats.

During those years I had three personal exhibitions in Pinar del Río, Havana, and Matanzas. Then I started going to Mexico, to biennials of visual and experimental poetry, until it became a violin of Ingres, something parallel to my writing. And I do believe that there are communicating vessels between my poetry and my stories and novels. I think so because there are certain moods, certain meanings that they all share.

Many writers, especially those who create their literary universe, have a “great theme” that runs through each of their works. Sometimes it is more noticeable, sometimes less, but it is always there. What is Pedro Juan Gutiérrez’s great theme?

That theme comes to me because of some of the big concerns I had when I was 20 or 21 when I decided I wanted to be a writer. At that age, I finished reading Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and I liked it so much that I set out to be a writer. It was a very important decision in my life. I had already read a lot, but that book was incredible, it gave me a shock. Then I said to myself: I want to write like this man so that it doesn’t seem like literature. And that is what still moves me. I was not interested in writing like Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse, Lezama Lima, or Carpentier. Not at all. What I wanted was to do something apparently very simple, very simple, very direct, and that didn’t look like a literary piece. And, well, it took me about 30 years to learn how to do it, but that was my path.

Then I asked myself: what do I write about, what will my subject be, what will I do. I knew that Hermann Hesse had his universe, that Rulfo had his universe, each one very well defined, very clear; but mine began to form precisely because of my lifestyle, which was always a lot of fun: women, alcohol, party. That was my world and that’s what I began to write about: those around me, my friends, some of the women I met. That’s how my great theme was defined, the one I think runs through all my books: poor people, simple people, people who have to struggle every day to survive, who have their own language, who live in a world where sex and alcohol are part of everyday life. These characters, who have always seemed to me to be anti-heroes, have no voice, and I wanted to give them one. I think that’s where my big theme is.

What do you think broke in Cuba with the Special Period, and what broke in Pedro Juan Gutiérrez?

The beginning of the Special Period coincided with the end of my first marriage, a very traumatic divorce. Then the economic problems also began. I remember that my salary as a journalist was equivalent to a carton of thirty eggs on the black market. Between the personal crisis caused by the divorce and the economic, social, political, and other cataclysms of those years, I opted to stay in a house in Central Havana, where I didn’t even have a chair to sit on.

The Special Period broke many things within me and my generation, within all of us who had dedicated ourselves with great enthusiasm to a political project that, suddenly, we saw was falling apart. What’s going on here, I wondered. And I did not understand. It took me many years not only to understand what was happening but also to learn how to thrive in the face of a new situation for which I was not prepared. I think the same thing happened to my whole generation. We were all used to living on a salary, to having a university degree, and overnight we had to face a much more individualistic, much more demanding, much braver life.

We all incorporated those new mechanisms that were then beginning to develop in the country to earn money and not starve to death. And I mean that literally, I am not exaggerating for effect or anything like that. That’s how it was for almost everyone. And my generation, well, some left the country, others became religious, others became alcoholics. I started drinking a lot of alcohol and had a lot of sex. Now I realize that all that excess was like an escape. I also smoked a lot and even had an emphysema that almost killed me when I was 44 years old. I quit smoking for a while, but then continued, despite the emphysema. I also suffer from a protein shock. Imagine, I had been two or three years eating only rice and beans, and suddenly, one fine day, a friend from Malaga who was visiting Cuba invited me to eat chicken and sausages and beers in Varadero. Then I lost consciousness and fell. My blood pressure was 40 over 40. The nurse who attended to me said: “Technically, you are dead. I can’t believe I’m talking to you.” Then I had a few coffees and my blood pressure improved and I didn’t die. But it was tremendous. Every time I look back to this incident, I laugh.

How did Dirty Trilogy of Havana come to be published?

The first two books of the Trilogy… I sent them to the publishing house Oriente, which was looking for books to publish again, but I think they were very scared because the girls who worked there never answered. Later I was able to recover the manuscript and I took it to an editor who was in Cuba, if I remember correctly, as a jury member for the Casa de las Américas testimony award. That was in January 1998. She took the book, read it in France, and found it very strong. She then sent it to a literary agent in Madrid, who also liked it. From there it ended up in Anagrama, Herralde read it and that was it. It was all very random, I think.

And how was it received in Cuba?

At first, nobody had read the book, which got a lot of press, especially in Spain. I was there, and when I returned to Cuba, in January 1999, they fired me from Bohemia magazine. I was very lonely here in Havana. Luckily, the UNEAC (National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba) defended me. After a few days of anxiety and uncertainty, I continued with my normal life. That is to say, they left me alone and I continued writing my books. The Trilogy… was published much later, in February 2019. They printed about three thousand copies… and without taking a single word out of it.

Publishing in Cuba was difficult. The first book that was published was Melancholy of Lions, by Ediciones Unión. I spent years without publishing anything and I had to talk with this and that publisher, until, finally, the thing was organized little by little and my books began to come out. Some 15 or 16 titles have been published, I don’t remember well. That means that, of my almost 30 titles, including poetry, half of them have been published in Cuba. Now none have come out because there is no paper, but there are two or three already prepared to be released.

Very often great success can condition someone’s writing, stylistically or thematically. Did this happen to you after the success of Dirty Trilogy of Havana?

I don’t think I’ve ever let success drag me down or paralyze me. If you think about it, my books after the Trilogy… were very coherent: The King of Havana, Tropical Animal. They came out one after the other. For example, Tropical Animal was born from an idea, the idea of love. I had written a terrible novel, The King of Havana, and before that the Trilogy…, which is also very tough. But I said to myself: I need to write a book about love. And that’s what I did. Tropical Animal tells a somewhat dramatic story, but, above all, a romantic one. Then I wrote the short story books Dog Meat and The Insatiable Spiderman, with which I completed the five books of the Centro Habana Cycle. After that, I began to change my environment: Our GG in Havana takes place in the year 55, El nido de la serpiente en Matanzas. I think I’ve been looking for other locations I’m interested in exploring because, in the long run, that’s what writing is: exploring your experiences, your life, and inside yourself.

Have you ever written thinking about those who read you, whether they will like it or not, whether the book will be successful or not?

No, never, because deep down I write to forget. I write from deep inside myself, and what I do is scratch things that should be forgotten and remain unperturbed. However, the writer’s life forces you to look at things that already happened many years ago and work with that. When I finish a book and hand it in, I feel good. The last one I handed in in June, and I felt good because I had already been revising it for a long time. That’s how it happens to me with every book: I get tired of revising, and correcting it, and one day I decide to hand it in. Then the process of forgetting begins.

I write to forget, to see if I am calmer and more serene.

What do you think it would be like to write the Trilogy… now, 25 years after its publication? Would it change much?

I couldn’t because that book is a great enjoyment of alcohol, sex, madness, traveling back and forth, and looking for money. And to a large extent that was my life at that time. I’m not going to say one hundred percent, but maybe 98 percent. Now, at 73 years old, it would be impossible for me.

However, I think the atmosphere is more or less the same in Centro Habana. The atmosphere in the neighborhood is almost the same as it was back then, with the same characters, and the same lifestyle. And I think so: today you could write Dirty Trilogy of Havana. Unfortunately, the neighborhood has not changed much. But, of course, I wouldn’t be the author.

I think that now more important than writing a book like this is to listen to the new contexts, the new voices of young people, who have other themes, other ways of expressing themselves, other anxieties and motivations in life. Every day there are more and more young people in their thirties who publish. This change is very important.

Tell me about that last book you recently handed in and that you are starting to forget.

Briefly, I can tell you that two years ago I bought a few Mecánica Popular magazines, the ones I used to read when I was a child. A bookseller had them, one of those who sell used books on Galeano Street, and I bought about five or six. I loved them very much in my childhood and I used to copy the house plans that came there. I even learned to do technical drawing by copying those plans. I started to read them after such a long time and, without realizing it, I got into their world of the sixties. Neighbors from Matanzas, from Pinar del Río, my mother, my father, friends, people from Havana, where I had uncles and cousins, began to appear in my memory. Before I knew it, I already had the first two stories written. I saw that there was a world that was opening up there, one that was uncovered when I went back to read those magazines. I guess I opened a drawer in my subconscious or I don’t know where. Next year it will be published by Anagrama.

Is it autobiographical?

It is not a book of memoirs or anything like that. They are just stories, like the ones I write, which are intermingled with each other and sometimes the same locations, the same characters appear in different tales. It is a book of short stories—although I recognize that it has a continuity that makes it feel like a novel—that explores the inner life of the people of the time in which the stories take place. Cuba from 1959 to 1962 was in transition and very different from today. I think I got very deep into that, and an interesting book came out of it.