Camilo Martínez Finlay, in memoriam

In the first few days of vaccination against the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, Carola Martínez Finlay was in upper Manhattan and volunteered. The city was devastated by the coronavirus. Thousands of elderly people had died. There were refrigerated trailers on the streets to store corpses. But a year after the virus began to ravage the world, science produced the first vaccines in an exciting and rapid process, and vaccination was underway.

Martínez Finlay, who works as Associate Project Manager at Columbia University’s Manhattanville campus, a job she describes as “super exciting,” knows the area well since she has lived there for twenty years, first in Washington Heights and then in Hamilton Heights in West Harlem. So she wasn’t surprised by what was about to become her main concern, beyond the pandemic: the difficulty of access for the poorest, most foreign and, above all, Spanish-speaking elderly people in those neighborhoods. Then she wrote a Facebook post expressing her disappointment and encouraging her friends in the city to help mobilize their neighbors. I maintain the urgent syntax of the SOS written on January 26, 2021 in New York City, the vortex of the storm: “I am at the Presbyterian helping with the vaccines, and I am very surprised that barely 1% of the older folks are Hispanic. Where are the people who live in this neighborhood? Doesn’t anyone inform them? This is a Hispanic neighborhood. Help me spread the word to those over 65.” That day and the next ones many other people sent similar messages. Like Carola, they wrote directly to public officials, some of whom took action. The mobilization of citizens multiplied. Despite foreseeable obstacles including ignorance and fear of the system, people were vaccinated. The path toward the city’s “normalization” in the months to follow is already known.

It is practically impossible for a reader born in Cuba to read the name “Finlay” in any context and not immediately think of Carlos J. Finlay, the most famous Cuban scientist. Moreover, when I read this particular Facebook post, I couldn’t help but think of a line uniting the efforts of the “Sage,” as his family called him to fight yellow fever in the last decades of the 19th century in the Caribbean with those of his great-great-granddaughter some 140 years later to ensure everyone in a New York neighborhood get vaccinated —even though they’re on different scales. Then, in Carola Martínez Finlay’s behavior, I envisioned the tension within a narrative arc formed by five successive persons in the Finlay lineage, in a sequence that led from the nineteenth-century doctor bent over a microscope to his great-great-granddaughter wielding an iPhone. It was a tension that forced me to think of the history of that family, some of whose members I treated over the years as a unit. The unity that in the tense string of that virtuous arc draws a series on another timeline, not Facebook’s, but a timeline of tradition, of the vocation of settling into history and being a part of it.

Perhaps another observer would have overlooked this. It didn’t go unnoticed to me, because I live for such things, these sensitive moments.

* * *

The five Finlays who string together this tale, three men and two women, are people born on the island of Cuba, but none of them has been strangers to New York City. We see or sense them portrayed against the backdrop of the city, as we observe them inhabiting the landscape of some disease that fancies itself a pandemic. Carlos J. Finlay fought against yellow fever. As his discovery remained unacknowledged for years, his son Carlos Eduardo Finlay Shine, devoted himself to vindicate his father’s figure and his discovery: he fought fiercely against the virus of oblivion. Years later, well into the 1950s, first, from their residence in an Upper West Side apartment, and then in Queens, Enrique Finlay and his daughter Olga, grandson and great-granddaughter of the Sage, respectively, succumbed to the enthusiasm for the figure of Fidel Castro. They were infected by the virus of the revolution, shaken by its chills, and awakened by its nights of delirium. Both held positions of some relevance at the service of the 1959 Cuban Revolution. Finally, Carola Martínez Finlay, Carlos J.’s great-great-granddaughter, escaped from Cuba in the mid-1990s in search for her dreams of being a mother and being free. She was able to realize both of them. At the end of this story, we’ll witness her standing in front of the house of artist and political prisoner, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, where she was confronted by the ferocious nightmare that many of us live in an unbearable state of wakefulness.

* * *

(Playlist #1: La quejosita, by Manuel Saumell) The monotonous buzzing of a mosquito wants to be the first tune you hear in this story. More precisely, the threat of a female mosquito’s bite. The kind that carried yellow fever from armpit to armpit. Let’s take a look at the XIX century to listen to her buzzing. Let’s go in order in this game of Roman numerals. The XIX, which looks like a fortress; the XX and its silhouette of rozsocháč, those “Czech hedgehogs” that cut off armored cars in two atrocious wars; and the XXI in which we’ll see the last line for vaccines. Yes, it’s out of fidelity to chronology, but also out of respect for that passion and spirit. Carola Martínez Finlay would not have been walking the trenches of volunteering if it weren’t for the fact that it’s in her blood. Because of the genius and the pulse that correspond to that blood and, in debt to it—a blood that, I would say, is another way of naming respect for tradition. Out of reverence to lineage. Call it “continuity,” if you like.

Carlos J. Finlay was born in Puerto Príncipe (what is now, Camagüey), Cuba, on December 3, 1833. Specifically, in a house that was marked number 4 (now number 5) Cristo Street, where his father, the Scottish physician Eduardo Finlay Wilson, had established a practice after having been accredited with the title of Latin Surgeon from Puerto Principe’s City Council. His biography is that of a dedicated practitioner of medicine and a talented man of science. He also possessed a voracious intellectual curiosity. He practiced different specialties and cultivated epidemiological research that turned his effigy into marble. He received the sweet reward of longevity, as well as the uncomfortable fate of posthumous recognition.

I don’t have any reliable data on his time in New York City, although there’s little doubt that he walked its streets. After beginning his medical studies in Europe, Finlay ended up enrolling at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia and graduating from there in 1855. In 1881 he attended the V International Conference on Hygiene held in Washington, the first and last of that forum to take place in the Americas, where he presented his theory of yellow fever transmission. He did so in a famous report in which he abandoned his previous hypothesis on the disease’s origin in miasmatic climates, in favor of one suggesting its transmission by a mosquito that bites a sick person and then transmits the disease to a healthy person. The English translation of Carlos Finlay’s paper, “The Mosquito Hypothetically Considered as Agent in the Transmission of Yellow Fever Poison,” was published that same year in the New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal. Originally, it was read at the August 14, 1881 session of the Royal Academy of Medical, Physical and Natural Sciences of Havana.

Rivers of ink have been spilled about the lack of recognition Finlay suffered and of how he was looked down upon. They pondered whether a Cuban was robbed of his discovery by the Yellow Fever Commission, headed by Walter Reed, operating in post-colonial Cuba. The Americans derisively called the Cuban “Mosquito Man.” From today’s hardened “watchtower” perspective, this is seen as a colonial gesture. The U.S. authorities would have liked to have taken it upon themselves to clean up the island, which they saw themselves as having helped become a republic. Hygiene and health as a whole would have to fall into the domain of the United States of America, from institutional hygiene to that of the underbelly where the ills of the tropics breed. Who should be credited with the solution? The person who first had the intuition or the ones who twenty years later proved it through experiments? That was the question.

Carlos J. Finlay died in the summer of 1915, recognized as both an effective civil servant, having been in charge of the public health of the nascent Cuba, and as a Sage—a term that should be pronounced here with the same heavy affectation it had in the past. Yet, he still needed his son’s help to become a revered myth in marble, obelisk, and the frontispiece of public buildings of a young republic in need of its pantheon of heroes.

* * *

(Playlist #2: Cuban Overture, by George Gershwin) One of Carlos J. Finlay’s sons stood out especially for the zeal he put into vindicating the memory—the same one that so many, including Fidel Castro and Fulgencio Batista, would denounce as sullied. It was he who fought against oblivion, which is the most tenacious and enduring of all the epidemics that we’ll see parading before us. He confronted it with the vaccine of the narrative.

Carlos Eduardo Finlay (1868-1944) followed in his father’s footsteps in his medical career. He became an eminent ophthalmologist. He studied at the same Columbia University where his great-granddaughter Carola now works and received an e-mail asking for volunteers to help with the vaccination process. At Columbia, the Sage’s son studied under Hermann Knapp whose method of cataract surgery was polemicized at the turn of the century. In specialized magazines from that era, it’s possible to locate records of Carlos Eduardo’s iridectomies, be amazed by his dexterity with the Daviel spoon, and imagine his patients, with their hands tied to the stretchers in Havana’s fin-de-siècle nights, hopefully cleaner than the century they were giving birth to. In his eulogy for Knapp delivered at the Academy of Medical, Physical and Natural Sciences held in Havana on May 26, 1911, Carlos Eduardo gives a usual summary of his professor’s merits and glories, but also slips in at the end some notes of a more personal nature in which he evokes the three years he spent with his teacher in New York City.

A quarter of a century after his father’s death, Carlos Eduardo wrote a book to defend him as the discoverer of the agent that transmitted yellow fever. He did not take kindly to Reed and the aforementioned Commission taking the laurels that the Sage’s brilliant and winning intuition deserved. The book was published in Havana by Editorial Minerva in 1942: Carlos Finlay y la fiebre amarilla. But that edition for Cubans was actually the second one. Before, in 1940, he published it in English (Carlos Finlay and Yellow Fever, edited by Morton C. Kahn), because the battlefield of vindication was fought in that language and in that world. To ensure that Finlay’s discovery of the eradication of yellow fever was recognized, he fought on all fronts. Those who profited from his discovery, such as William C. Gorgas, responsible for sanitation during the construction of the Panama Canal, where yellow fever was decimating workers, also pushed in Finlay’s favor. Gorgas was active in promoting the Nobel Prize for Finlay, a distinction for which he unsuccessfully nominated him seven times.

Carlos E. Finlay’s efforts sealed his father’s glory. The pedestal he cemented in his memory would not suffer any erosion from now on. Thus, Carlos J. Finlay was extolled with the same degree of patriotism by Fulgencio Batista and Fidel Castro, the sergeant and the commander, the coup leader and the revolutionary, both of them united in their praise, and closing their ranks in honor of their compatriot.

On December 3, 1993, it was Fidel’s turn to deliver the closing speech at the inauguration of a vaccine plant at the Carlos J. Finlay Institute. He said he was reluctant to do so. Three decades were still to come before the Wuhan disease took over the world, and “Abdala,” the name of one of the Cuban vaccines against that plague, was but a title of a modest drama in verse by José Martí and, consequently, the name on a sign on a random kindergarten in Havana! At the event, José López Sánchez spoke. He was the author of a biography of Carlos J. Finlay that, believe it or not, the Colombian Gabriel García Márquez called the best biography ever written in Cuba. The book, written at the request of the Commander-in-Chief was entitled Finlay. El hombre y la verdad científica, and its author, López Sánchez, was a Spaniard who arrived in Cuba after the Spanish Civil War and was said by Granma on June 6, 2004 to be the oldest living member of the Communist Party in Cuba. At the event, an exchange took place between the two of them, which is included in the official version of the speech. It is one of those dialogues typical of the Cuban dictator: López Sánchez is asked to confirm the proposals of his soliloquy. Judging by the stenographic notes of the meeting kept in the archives, López Sánchez plays the role of courtier very well. Castro ends in the following manner: “It is very sad to know that Finlay’s merit has been so disputed. It is not a question of chauvinism, but the fact is the paternity of the discovery, the paternity of that theory has been totally and absolutely proven. I recently read that for many years there has been talk of whether to give the Nobel Prize to Finlay and that, in the end, due to the opposition of certain interests, he was not awarded the prize, so that even in that, they were unfair to Finlay, and that very recently a book was written in Europe contesting Finlay’s merits. That is why we must continue to fight. We believe in this with very deep conviction.”

A few decades earlier, in his own bad decade, Fulgencio Batista, more restrained in his expression, was just as hurt. The booklet here before me, A Tribute to Finlay, published in English by the Ministry of Public Health, outlines the First InterAmerican Congress of Hygiene, held in Havana between September 26th and October 1st, 1952. It pays a “a solemn continental tribute” to the figure of Carlos J. Finlay. Hygienists from Brazil and Panama, Nicaragua and Venezuela discussed various details regarding the struggle to eradicate yellow fever. Minister Enrique Saladrigas y Zayas concluded with a “Eulogy for Finlay,” in which he praised Finlay and his contributions. He closed his speech and the Congress, of course, with a few words from Batista, present in the room: “Finlay,” General Batista said, “was one of those scientists for whom humanity can never do enough…”

The unanimity around the figure of Carlos J. Finlay exceeds the shoulder to shoulder of Batista and Castro. Every Cuban who’s more or less my generation knows the meaning of the charges “intellectual author” and “transmitting agent” presented before distinct courts. The first, presumably honorable, involves Martí, whom Fidel proclaimed “intellectual author” of the attack on Moncada; second, as an unmasked criminal, is that of the mosquito spreading yellow fever. Perhaps José Martí and Carlos J. Finlay are precisely the only two Cubans who enjoy undisputed prestige among the natives of that island. An Apostle and a mosquito killer: the victim of a raid in Dos Ríos and the hero of Raid® that shoots out Flit insecticide. Politics and truth. Mysticism and method. Magic and science. (Maybe the famous singer Benny Moré and the chess champion José Raúl Capablanca also enjoy such unanimity, but that, perhaps, would be too much to ask.)

There’s a museum in Havana dedicated to him, and the house where he was born in Camagüey is also memorialized. In addition, there are three monuments in Havana’s Marianao municipality. I myself grew up in the shadow of one of them, the famous Obelisk of the airport of a different Columbia, one that was a barracks before it was a school. The Institute of Epidemiological Research and the National Science Award bear his name. Carlos J. Finlay is also the name of the Military Hospital in Marianao, another building installed on the grounds where I spent my childhood. I went to that hospital one day to drop off a man I found half dead on a highway. I also traveled there from Barcelona to say good-bye to my fearful and absent mother, already beginning to die. Finally, there’s a University of Medical Sciences called Carlos J. Finlay.

As for New York City, the most lasting imprint that Carlos J. Finlay on it was likely a result of the eradication of yellow fever which, having preyed on the workers building the Panama Canal, impacted the Stock Exchange. In the process a wound was inflicted on the Central America isthmus, and world commerce was revolutionized. The Sage’s great-great-great-granddaughter, born in New York, already a teenager on her way to college, buys her drink every morning in front of that impetuous bull, the Charging Bull grazing on Wall Street. She orders a Vanilla Chai Latte, to be precise.

* * *

(Playlist #3: The Goin’s Great, by Sammy Davis Jr.) Many years after Carlos Eduardo Finlay fought for the legacy of his father, one evening few years ago, Carola and I found ourselves at Grand Central Station. I don’t know what exactly we were doing there. It was freezing cold outside. We were entering from a side street when suddenly, the MetLife Building at 200 Park Avenue seemed to fall upon us, and Carola uttered, “That’s where my grandfather Quique worked when he lived in New York, when it was the Pan Am building.” I thought it was kind of funny that the mosquito chaser’s grandson worked for an airline. “We should write that story,” I said to both of them—to Carola and the night.

Enrique “Quique” Finlay, Carlos J. Finlay’s grandson, was born on 1906. He will be seen making an appearance very discreetly in the history of the 1959 Revolution, the one that will end up turning Cuba into the physical and moral dunghill that it is today. But Enrique Finlay couldn’t have known that end. For example, his wife Nena Saavedra rolling her own cigarettes using the leftovers of cigarette butts that others picked up on the sidewalks, surrounded by the misery of the 1990s, which we, naive and stoned, called late-Castroist. Sometimes I like to think that what Cuba would end up being, in reality, no one could have known for sure back then. An excuse that is severely attenuated by evidence that many people already sensed that it could be even worse. An excuse that also needs to take into account another undeniable variable: namely, that Enrique and Olga wanted the Cuba inherited from men like Carlos J. Finlay, the country where their children and grandchildren would be born and grow up, to be a better, fairer, and freer place. And they saw in the revolution that overthrew Fulgencio Batista the way to achieve it. They were victims of an atrocious confusion, because the children for whom they built a future ended up finding it as despicable as the Cuba their parents rejected. Revolutions are often a great sea of confusion in which the ships of hope capsize. And, yes, we will also get to the rafts, the sea, and that moment before capsizing.

Pointing to the windows of the building, Carola was creating more confusion, but perhaps this time it was the fruit of one of those myths that families cultivate. Enrique Finlay worked for Pan Am Airlines, indeed, as he did for Merrill Lynch, but he couldn’t have worked in a skyscraper whose construction began in 1959 and rose 59 stories. Because Enrique returned to Cuba to work in situ for the 1959 revolution, and those double, triple fifty-nine’s would’ve been too many for him. A terrible redundancy. It was not until March 1963 that the Pan Am headquarters building was inaugurated. By then Enrique was no longer there to say his “Good morning,” well-dressed and smelling like Old Spice, in one of the elevators. He had already given up on his anti-Batista emigration to return to revolutionary Cuba. He was already a “repatriate,” as the newspaper Revolución, proclaimed when giving news of his return. Enrique Finlay returned burning with revolutionary fever and anti-imperialist rage—a combination of spirit and conviction that served him perfectly in Havana, where he resided for the next three decades.

* * *

(Playlist #4: Manteca, Chano Pozo, Dizzy Gillespie et al., performed by Chico O’Farrill) Chico O’Farrill, known as the architect of Afro-Cuban jazz, was one of Manolo Saavedra’s cronies who was responsible for Enrique Finlay and his daughter Olga, the Sage’s grandson and great-granddaughter, settling in New York. Miguelito Valdés and René Touzet also shared music and interests with Manolo. The young Saavedra organized jam sessions in Havana. Those nights they’d listen to records from the collection he was beginning to put together along with those he brought back to Havana when he returned from his studies at a military high school in New York between 1927 and 1929. Manolo Saavedra is considered to be one of the people who helped bring jazz to Cuba. He himself was a guitarist who once dabbled in becoming a professional musician, but never made a career out of it. He never cut himself off from music, however, just as he never definitively cut himself off from the Cuba he left in 1949 to which he would only return occasionally. On account of his attachment to the latter, one can understand his reluctance to acquire U.S. citizenship, a gain that, whether for borrowed patriotism or a mere civil and administrative advantage, immigrants to that country usually covet. Manolo died in Miami in this millennium while still a Cuban national, because he never wanted to apply for citizenship, selling his last guitars (some of them sold on eBay for about $5000) to pay for the care that his physical fragility demanded.

When Carlos E. Finlay’s died in 1944, his beloved children sold the family home in Vedado, located where the parking lot of the Trianon Cinema/ Theater is today, on the corner of Línea and Paseo, and, taking advantage of the money from the property’s sale, each one went their own way. Some family sources suggest that it was the political situation in the country, that Enrique felt uncomfortable with, that pushed him to leave for New York. While that could be, when he left in 1950, it was still a couple of years before Fulgencio Batista installed himself in the Palace after a bloodless coup d’état. In any case, when the coup does take place, Enrique is no longer there to see it up close, because he had gone elsewhere. To the Upper West Side, specifically. The Sage’s grandson traveled there with his wife Milagros “Nena” Saavedra, Manolo’s sister, and their daughter Olga Finlay. Olguita. Then, it was Manolo Saavedra who drew his sister Nena and his brother-in-law Enrique to the New York of 1950. He provided the rope they used to climbed North. The Revolution would provide the grease that helped them lower themselves later. Manteca, I’m telling you!

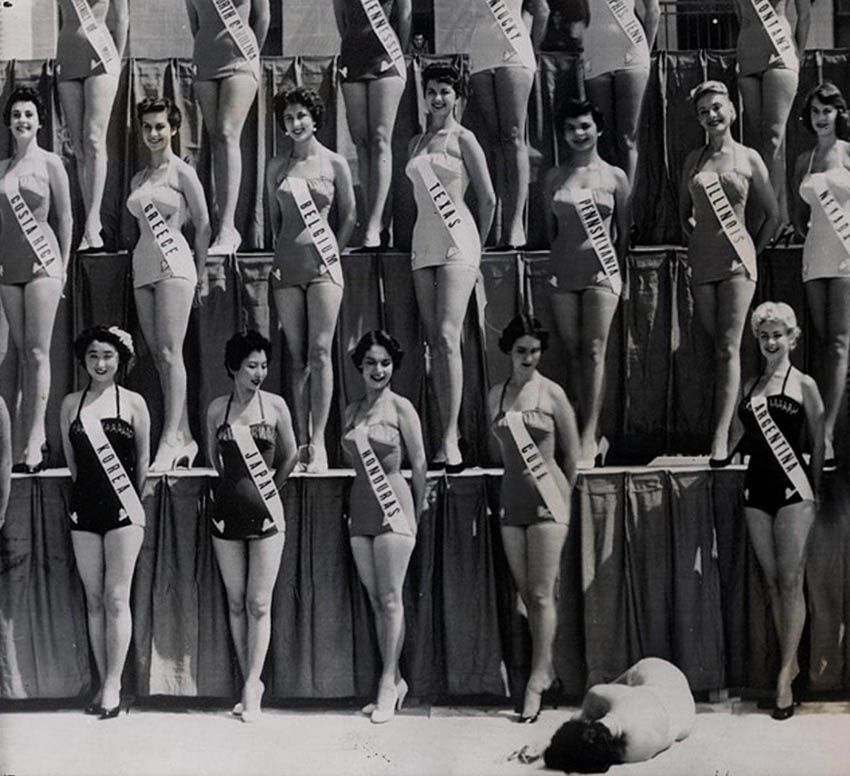

Enrique’s emigration to the U.S. was a rather unique event among the Finlays. Most of his relatives remained in Cuba in the fifties and made intermittent appearances in newspapers. Isis Finlay, for example, grandniece of the Sage, entered the Miss Cuba contest in 1954. The young Isis, who truth be told, does not look very attractive in the photograph I’m looking at, bet with a friend that she would enter the contest, honored the bet, and ended up winning. With the Miss crown she traveled months later to represent Cuba in the third edition of the Miss Universe pageant held in Long Beach, California. There she wasn’t lucky and didn’t even manage to qualify, which also meant qualifying Cuba, among the sixteen finalists. On the occasion of her death in a traffic accident on May 24, 2007, her son-in-law Jeremy Fisher told the Miami Herald that Isis was a happy woman and very fond of traveling: she visited 51 countries in six continents. The archives also show Frank Finlay unveiling a plaque in honor of Carlos J. Finlay in the company of the aforementioned minister Enrique Saladrigas. The photograph is from December 3, 1952 at Camp Lazear, in the Havana neighborhood of Pogolotti. I’m shocked by another photograph just sent to me by a friend who went to see the current state of the monument.

Like a good part of the Finlay’s male lineage, Enrique was a handsome guy, with an elegant demeanor and a gravity about him, but also somewhat jovial. This is how he lives on in photographs and in my memory, as we were introduced one day in Havana. Back then, in the summer of 1988, I was a student at the Moscow Institute of International Relations on vacation on the island. From the brief conversation we had, I only remember that we talked, and I don’t know why, about the phrase “Indian Summer.” I told him the expression the Russians used: Babie Leto, the summer of the peasant women, or, perhaps better, of the maidens.

Like so many other Cuban émigrés in the United States in the 1950s, Carlos J. Finlay’s grandson was enthusiastic about the struggle against Fulgencio Batista. It’s difficult to tell exactly when the Finlays began to collaborate with the revolutionary struggle in Cuba. But what is certain is that Enrique, Nena Saavedra, and Olga were intoxicated by that cocktail, in whose glass—cut by the disorder of the century—exile, patriotism, and illusion were mixed, dragging them into the revolution’s vertiginous course.

At a point of being won over by enthusiasm, Enrique and his daughter Olga confound the chronicler: what comes first, the chicken or the egg? Which of the three kicked off the family’s commitment to the Revolution? Was it the formal Enrique, who was the closest heir to the origin of a tradition? Or was it in the blood of the young Olga whose desire to be Cuban, to be something else, boiled hotter? Was she the one who fed the desire to be a “Red Indian,” like the young Franz Kafka? I must confess that I’ve enjoyed emphasizing that perfect middle position that Enrique occupies in the series of five successive Finlays in these pages. I liked the idea, pure symmetry, of pivoting the story on that bald, mustachioed man, a man in whom I clearly perceived the imprint of the inheritance of the greatest Finlay. But the facts, when you line them up, amount to more than any photo. And the facts favored Olga. So do the testimonials, as well as the photos, or at least a couple of them. So does the archive. Olga is the one who steps forward, the one with an eagerness to take the sky by storm. And although I would have preferred to stay with Enrique, to whom I am united by the memory of a chat, a shadow, some phrases, Olga is the life and soul of the fiesta. Of both Lezama Lima’s “unnamable fiesta” and Antonio José Ponte’s “supervised fiesta.” Let her come in, then.

* * *

(Playlist #5: West Side Story: End credits, by Leonard Bernstein) Olga Finlay Saavedra, great-granddaughter of Carlos J. Finlay, mother of Carola, was born in Havana on September 23, 1939. As time went by, she became an official of a certain level in the power machinery of the Revolution. She worked in the office of Raúl Roa, the so-called Chancellor of Dignity; she accompanied Cecilio Martínez, her husband, to the Cuban Embassy in Stockholm; later on she worked until her death with Vilma Espín, the wife of Raúl Castro, the Minister of the Armed Forces and brother of the dictator. From that last position in the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC), she went on to defeat the U.S. State Department in a case decided by New York courts. And she would become, above all, the mother of four children who mourned her when cancer took her too soon to a world without hope or revolutions.

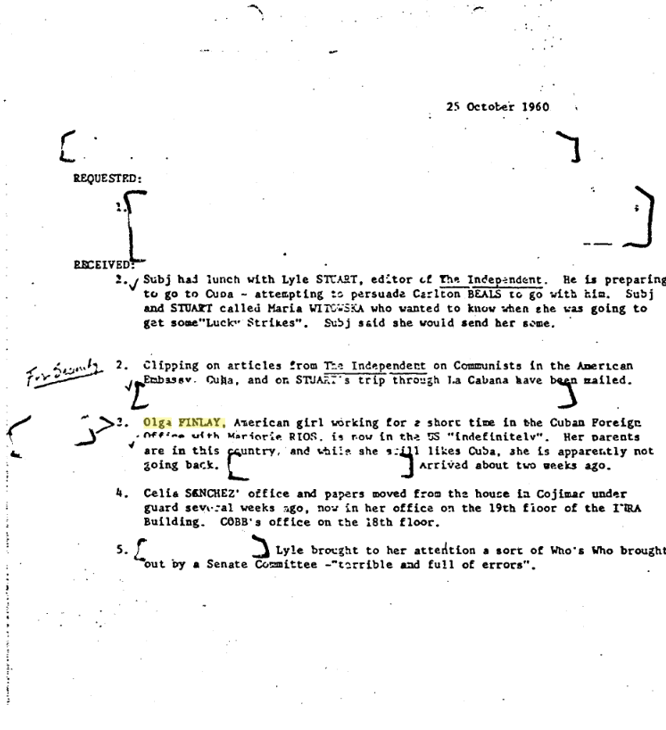

A CIA document dated October 25, 1960, when Olga was already working for the very new regime in Havana and had also captured the attention of J. Edgar Hoover’s men, refers to her in these terms:

«Olga Finlay: American girl working for a short time in the Cuban Foreign Office with Marjorie Ríos is now in the US ‘indefinitely’. Her parents are in this country and, while she stills likes Cuba, she is apparently not going back. (…) Arrived about two weeks ago»

Isn’t it fascinating? And it is so because of the magnitude of the big mistake, as well as the recklessness of a small one.

Olguita arrived in New York in 1950 as a young child. Data about those first years of her life in the city are scarce and confusing, but you know what Liev Tolstoy wrote about happy families. She seems to have finished high school in the Upper West Side, where her parents rented an apartment. Probably at the High School of the Blessed Sacrament, class of 1958. One can imagine New York and what it was like to be young for these girls in the 1950s. Literature and photography help. Garry Winogrand and Sylvia Plath seem appropriate. Film and music help too. Out of all the cinema and music of those years, I know they came together in West Side Story, and that’s why Olga, already in her twenties, fell in love with it. Imagine that young woman from a Cuban family living with her parents in New York. Uncle Manolo carrying records and boxes of fried chicken. Together in the family album the love for music and the disaffection for Batista’s Cuba. “Another Cuba is possible,” they would say to each other over roast beef and an episode of I Love Lucy played that night. They were right: it was possible. Just like so often Desi Arnaz was right before the furious Lucille throughout so many nights of that decade. One hundred and eighty nights of the program, to be precise.

With the triumph of the revolution in January 1959, Olga and Enrique began to travel to Cuba, to take part in it. It wasn’t so long before they enthusiastically repatriated. These were intense months in which, for sure, there were doubts about a definitive return. It seems that Olga was more inclined toward Cuba. After all she was only a young woman in her early twenties who identified herself with the generation that was coming to power, while Enrique and Nena were more cautious. All in all, it was history that decided for them. The trigger was a gimmick that Castroism, still in its early days but already skilled in AgitProp, installed in New York and from there spread throughout the United States: specifically, The Fair Play for Cuba Committee, better known by its acronym FPCC, a tool to support Castroism that had a brief but explosive life. Because of it, the Finlays were sent packing on their way as Cold War agents, amortized and shrouded in the pages of a novel or between the covers of a dossier.

On April 6, 1960, the FPCC placed a full-page advertisement in The New York Times. The ad appeared one year and ten days before the disastrous landing of Brigade 2506 in the Bay of Pigs, in the south of the Matanzas province and a year and four months after the triumph of the revolution. With that announcement a phenomenon began that has grown over the years, but with that very same script: activists and intellectuals, largely from the U.S., sign on to support whatever Cuba is. The last of these letters, paid advertisements in the newspaper that’s considered the most important in the world, was published on July 23, 2021. “Let Cuba Live,” it cried out, and it was signed by hundreds of people, individuals and groups, who were ignorant of what Cuba actually is. And also others who know and support what Cuba is. But let’s go back to the firstborn, which is the one that concerns our Finlay. Its headline read, “What is ‘really’ happening in Cuba?” where the “really” is inserted in the sentence with indiscreet typographical flair. The text functions as a correction of the alleged falsehoods published by the U.S. press about Cuba. It promises to offer only “facts” about the communist nature of the revolution, the nationalizations, the militarization, etc. It is a charming collection of fallacies, which are noticeable not only from the comfortable retrospective seat that grants us the knowledge of the grotesque subsequent reality. The list of American intellectuals who signed it was extensive and included notable names such as James Baldwin, Truman Capote, and Norman Mailer. It also included many writers and activists who would play a more active role in disseminating information and awareness about the Cuban process. For example, the French Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. American journalists and writers more directly linked to the cause of the left, such as the reporter Robert Taber and the writer Waldo Frank, who shortly afterwards published The Prophetic Island: A Portrait of Cuba, a commission paid for by the Cuban government, also lined up for the illusion. Frank is listed at the bottom of the advertisement as president of the FPCC.

Curiously and significantly, a few days after the advertisement was published, on April 19, 1960, in the Letters to the Editor section of the New York Times, another letter about Cuba and the desire for the truth about what was happening there appeared. It is signed by only Enrique Finlay, a resident of Jackson Heights, N.Y., and is dated April 1. It is a harsh reply to a letter signed by President Eisenhower to the Chilean Student Federation regarding Cuba. Enrique shoots to kill. He writes that the letter of the American president “represents an aggression to our revolution and our country.” The Sage’s grandson dedicates the bulk of his letter, which is brief, as required in that section, to make excuses for the Revolutionary government due to its reluctance to call elections, 18 months after the triumph, the deadline previously set for this event. Finlay points out how long it took for the U.S. intervention governments on the island to call Cubans to the polls (three and two years, respectively) and of Batista he says it took him “almost four years” to hold elections. Then, he goes on to say, Fidel was still in time. Ah, but it is hard to spare a smile if one counts the days remaining until May 1 of that same year when, in what was still called Civic (and not yet Revolutionary) Square, Fidel summoned the people and delivered a speech of which a single refrain, a single clamor is remembered: “Elections? What for?”

Did the Cuban government pay for the New York Times ad? Did the revolutionary government pay for The Fair Play for Cuba Committee’s activities? This question interested the U.S. State Department, the FBI, and the U.S. Senate. And their scrutiny led to one of those convoluted spy stories of which the Cold War is chock-full. Let’s just stick for the moment to the story handled by the FBI and the ad hoc Senate committee, which is ultimately what drove the Finlays out of New York.

On January 10, 1961, a hearing was held in the U.S. Senate. Charles Santos-Buch, a Cuban medical student who had participated in the meetings was called on to testify, for at least the second time. It is curious to mix things up a bit, and let it be known that Santos Buch stood out in research on Chagas disease, the American trypanosomiasis, transmitted by insect bites. Neither did he deny himself the pleasure of writing a family history in a celebratory tone. Let’s call the mischievously titled book, A Differing View of Cuban History (still available for purchase on Amazon), a healthy vice he indulged in.

The story that Santos Buch told about the money trail was as follows. At a meeting that took place at a Cuban restaurant in New York (“I don’t remember whether it is the Liborio or El Prado”), it was agreed upon to launch a campaign in favor of revolutionary Cuba by taking out a full-page ad in The New York Times. The ad was not going to be cheap, and money had to be raised. The instigators then circulated a copy of the text among New York intellectuals and sympathizers. The pockets of these supporters handed over about $1,000, which wasn’t enough to satisfy the Old Lady’s appetite. That’s when the operation crossed over the border into the realm of the illegal, always following Santos Buch’s version. “Where did you get the rest of the money?” asked Senator J. G. Sourwine, in charge of the bulk of the interrogation. “We obtained it from Raulito Roa,” Santos Buch answered and explained how Taber and he went over to the apartment of Raúl Roa Jr., who was at the time a member of the Cuban delegation to the United Nations. He wrote a check for $3,500 that, after several failed attempts, he ended up cashing himself at the United Nations headquarters, where he was known. By the way, the New York Times bill was for $4,725, revealed when the Senate Committee urged the newspaper to make the amount known.

The matter was not trivial: if the money came from the Cuban government, the Fair Play for Cuba Committee was acting as a “foreign agent” on U.S. soil illegally. Although there’s no evidence of Enrique or Olga Finlay being directly implicated in this affair, in some of his conversations with the investigators, Santos Buch mentions Manolo Saavedra and Enrique Finlay as two of the people who knew about the activities of Raúl Roa, Jr. Santos Buch also says that he thinks that, at the date of his statement, Enrique Finlay and his brother-in-law are probably still members of the FPCC and “pro-Castro.” Another clue in a document, already cited, points out that Olga Finlay would have worked those months for Marjorie Ríos, a colleague of Raúl Roa, Jr.

In any case, the traces of Enrique and Olga Finlay’s activities in those first two years of the Revolution are abundant. Intelligence reports actively link Olga with Cuban offices in New York and the coming and going of elements favorable to the Cuban government between New York City and Havana. In line with the advice given by Marcelo Fernández Font’s to Raúl Roa, Jr., a report dated May 9, 1960 orders a plane ticket be authorized in Olga’s name for a May 10th Cubana de Aviación flight to Havana. Once at her destination, “Finla,” as she is referred to in the dispatch, “was to report to FERNANDEZ to receive instructions.” Fernández Font, an active member of the 26th of July Movement, who would occupy high-ranking responsibilities in the Cuban State throughout his life, served as Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Revolutionary government in those days. Other intelligence reports mention ticket reservations to Havana on behalf of the Cuban State for the two executive figures of the FPCC in New York on those same days. Waldo Frank was to fly on April 28, and Robert Taber was to fly the following day, although it is true that there is a reference in the archives that indicates, according to Elizabeth Hirsch, Cubana Airlines employee in New York, that the flights for them both were booked for the opposite dates.

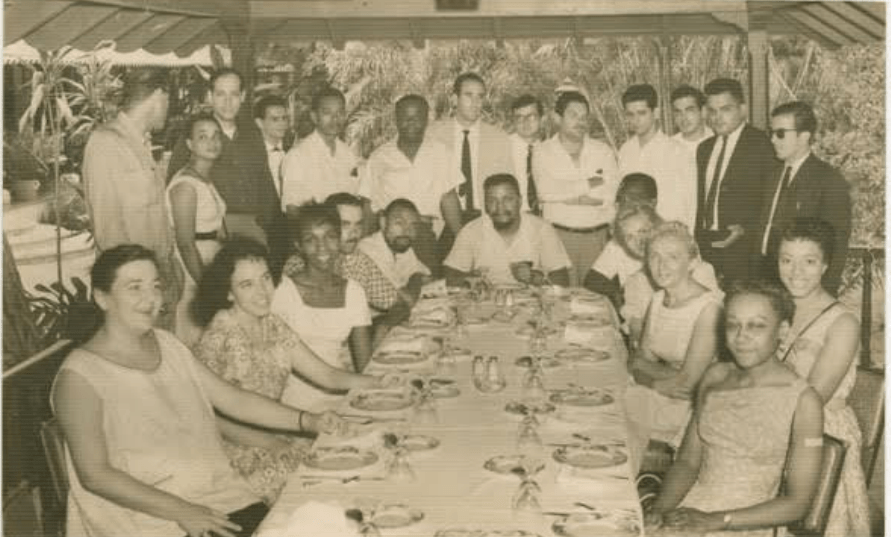

There are other traces of Olga’s work in Havana to which she flew from New York accompanying fellow travelers. Thus, for example, the “American girl” in the CIA reports is, for the noted African-American writer and activist LeRoi Jones, later called Amiri Baraka, “a small pretty Cuban girl.” Jones visited Cuba with a group of American intellectuals and activists in July 1960 and published his chronicle in Evergreen Review, a beatnik magazine. His trip entailed a tour of the entire island. Pure revolutionary orgy commemorating an anniversary of July 26. The trip was organized by The Fair Play for Cuba Committee and sponsored by Casa de las Américas. The young Olga Finlay, who traveled from New York for the occasion, served as cicerone and interpreter to the enthusiasts. In Jones’ chronicle, a reception with a “Calypso band” and daiquiris was waiting for them at the José Martí airport from the very first moment, where Alberto Robaina, at the time vice-director of Casa de las Américas, and Guillermo Cabrera Infante, whom Jones calls “poet,” were also present. Also in connection with Olga, Jones includes a funny confusion, because he says he later learned that she had lived about ten years in New York and “was the granddaughter of a high-ranking official of the revolutionary government.” That would have been Carlos J. Finlay, mentioned among cups of rum and confused with the convulsive present time. Or, perhaps, his grandfather Carlos Eduardo, who briefly served as Secretary of Health in the 1930s.

This troupe, the first mass delegation of FPCC members to visit Cuba, also included Robert F. Williams, another Black activist who, deeply impressed by what he saw on the island, ended up growing a Fidel-like beard. When Williams visited Fidel Castro in Harlem a few months later, he was convinced that a firm link had been established between Black activists and the Cuban revolutionary hierarchy. Robert F. Williams’ is the last signature at the bottom of the FPCC ad in The New York Times. His history with Cuba, by the way, will conclude with an intervention by Enrique Finlay, as we will see later.

That the Finlays—Olga and Enrique—slipped in among the platoons fighting the Cold War made them persons of interest for the CIA and FBI. By then the Finlays had left their Upper West Side apartment and moved to Queens. Enrique worked for Pan Am, an airline company with origins in the 1920s in the U.S.-Cuba traffic of mail and desire. It grew to be one of the largest airlines in the world. Nena, his wife, took care of the house. I heard a vague rumor of Olga selling umbrellas after her graduation.

But the downpour of the Revolution was soon to provide her with a much larger umbrella under which to shelter her impatience. In late 1960, in between one of her trips back and forth to Havana from New York, Olga Finlay was hired by Prensa Latina to work in the bureau the agency had set up in Manhattan. June Cobb, the mythical CIA informant, says that Angel Boán, one of the people in charge of Prensa Latina in the city, told her about the hire in a call he made on November 6, 1960. Boán’s contentment was evident, and Cobb notes on a pad with the letterhead of the Park Chambers Hotel, 68 West 58th St., NY, the following: “He told me he had hired Olga Finlay a few days ago. He is teaching her to be a teletype operator.” Boán complained that everyone with the skills to work at Prensa Latina are “politically corrupted,” and he went on about how happy to have found Olga “…he was very happy to have Olga since she was someone they could trust”. Another CIA document assures that Olga returned from a trip to Havana in mid-October, so it is reasonable to think that she was already returning with the recommendation: “someone they could trust.”

Olga had already caught Cobb’s attention before, which shows that, in spite of her youth, she occupied a not exactly trivial place in the affairs that Cuban activists were moving in New York. Thus, Olga appears in several of her notes those months and, notably, in one dated October 26, 1960. So, two weeks before Boán distinguished Olga as someone he trusted, Cobb already had her sights on her.

Let’s read this note—a full-fledged operational profile— not to be missed. It bears Olga Finlay’s name as its title and reads, in typewritten text:

“This young lady is very discrete. I took her for tea at the Palm Court [please note Cobb is referring to the famous, sophisticated, and tropi-baroque Palm Court of the Plaza Hotel no less!] after about an hour here in the apartment. She is very clearly anti-Communist orientation but reveals only in discussion of Russia and Khrushchev, never in remarks about what is happening in Cuba. She is not willing to see (or is not willing to let it slip she has seen) any kind of communist infiltration in Foreign Relations. At one point she even said to me, ‘I can’t believe what they say, that Olivares is a Communist.’” Cobbs also slips in that Olga was educated as a member of the middle class and that her former classmates perceive her now as “a communist.”

Cobbs also notes in her report that Olga reportedly spent five months in Havana in 1960 working as a volunteer for INRA (National Institute for Agrarian Reform) and was later hired by MINREX (the Ministry of Foreign Affairs). Now, she concludes, she would have returned to the United States “transferred.” In short, it seems that Cobbs, translator into English of Castro’s History Will Absolve Me, which was a spectacular cover story, earned her dollars doing good profiles. From her reports and notes, it is clear that Olga Finlay worked in New York for the revolutionary government.

She would not do so much longer, for her time in the Big Apple was coming to an end. When Olga leaves to serve the Revolution in Havana, more than thirty years would pass before the first of her daughters settles in New York, having fled to Western Europe from the USSR when it was her turn to go back to Cuba. The second, Carola, will settle in Manhattan at the brink of the century and the millennium, in 2000, with the Cuban Revolution still alive and hated.

On March 7, 1961, the FBI agents James J. Conway and Francis I. Lundquist came to question Enrique Finlay about the check, the announcement, and the activities of the FPCC. Both showed up at the apartment in a well-proportioned house at 35-57, 87th St., in Jackson Heights.

Those early March days are usually bright and cool in New York. On that 87th Street, with its three-story American Colonial-inspired houses and Elizabethan air on both sides, they would be watched by some crow, perhaps a weasel glanced sideways at the agents’ well-shined shoes. Quique or Nena opened the door. Those two guys had come to talk about important things. But none of the four knew yet how important they would be to the Finlays. For the agents it was a routine task. For Enrique Finlay, Carlos J. Finlay’s grandson, it was a procedure he was compelled to face by the commitment to his lineage, inseparable from his commitment to Cuba. A cumbersome procedure, naturally. For Olga Finlay, who will soon appear in the apartment, surely warned by her mother in a brief telephone call, that visit was a bite from the enemy.

The report of the meeting is brief and shows Enrique Finlay’s reluctance to cooperate. He claims that he has to consult his lawyer. When asked for the lawyer’s identity, Enrique refused to provide it. One imagines him to be somewhere between indignant and cautious. The report adds this: “In the course of explaining his legal rights to Finlay, his daughter Olga Finlay, entered the apartment with her employer, Ángel Boán of Prensa Latina, the Cuban news agency.” The meeting ended with that intrusion.

After being advised, Enrique agreed to be interviewed at last. The new meeting with the agents took place on March 14. Quique denied practically everything, except for having attended between five and ten meetings called by the FPCC. Of Roa, Jr.’s money, he said he was inclined to think that Santos Buch had lied and that he gave more credibility to the testimony of Robert Taber, who had testified to the contrary. He admitted, however, that while in Cuba in January and February 1960, he had heard a committee was being organized to promote US-Cuba relations. He also admitted knowing Raúl Roa, Jr. and Waldo Frank since the 1930s in Cuba. When asked to elaborate on his relationship with the Committee’s leaders, he said he would not say anything more without the assistance of a lawyer.

In front of me is a photograph of Enrique Finlay, Nena Saavedra, and Olga landing at Rancho Boyeros airport on a Pan Am flight. It could be from that 1960 trip that Enrique referred to in the interrogation. The photograph shows him descending the stairs of the plane. He is carrying an overnight bag in his hand. He has stopped for a moment, leaning on the railing and looks ahead, at the group that is receiving them. His wife and daughter follow him a few steps higher, both elegant and happy. Now perhaps it is difficult for us to imagine the enthusiasm of the emigrants returning to a country they believed was finally liberated from tyranny and healed, with a bright future in which they were invited to participate. That is the feeling these faces convey. And the gestures: Olga’s involvement with other young revolutionaries, the letter that Enrique wrote to the Gray Lady, the different commitment his brother-in-law Manolo and he made to the new revolutionary power… It is also possible someone might believe that in the current situation of things in Cuba, sixty years after the triumph of that revolution, we could find ourselves again before similar episodes: people getting off the plane with happiness on their faces and their overnight bags full of banknotes and after-shave. However, on the day that photograph was taken, the Finlays were not yet the exultant repatriates we will soon see shouting in the pages of the newspaper Revolución.

The agents’ visit and the subsequent meeting put Enrique in an uncomfortable position. Perhaps Olga found in that discomfort the lever to convince her parents to return. The following months will be exciting for her, however. Olga is hired by Boán one day in mid-October 1960, and on March 7 she bursts into the apartment where her father is being questioned, accompanied by Boán himself, in what seems to be a counterintelligence operation. A year later, between comings and goings to Havana accompanying people and bringing missions, Olga appears in a photograph taken on May 16, 1961 at the Prensa Latina office at 580 5th Av. in New York. It’s an important photograph in the history of the agency founded by Jorge Masetti, and it’s still for sale on the Prensa Latina website. There’s a good reason for that: it features Gabriel García Márquez, the Colombian journalist and novelist. Olga does not occupy a peripheral place in the photo. In fact, in none of Olga’s public photos is she seen standing to the sides. Nor does she look grave. In many she smiles. In some she laughs heartily. In the one taken at the Prensa Latina office in New York, she appears in the center, next to Ángel Boán, which makes sense, since they are the hosts. Gabriel García Márquez is squatting in front of her. Incidentally, the photo for sale does not include Olga in the credits. In the history of Prensa Latina, as, indeed, in the history of MINREX, and we will see it soon, Olga is a nobody. And writing these lines or tracing her itinerary prior to doing so, I cannot resist the temptation to think that I am the only one who is interested in this revolutionary. That’s how strange we counterrevolutionaries are, you might say.

I want to ask about Olga but there’s hardly anyone left among the story’s main characters to ask or anyone it would be prudent to. In the absence of founders, I interrogate documents. I also sometimes call the characters’ children, when I am lucky enough to have them within reach of WhatsApp. Of course, I speak with Olga’s children. But I also look for her elusive silhouette by calling others who descend from those who had dealings with her. For instance, I speak to Jorge Masetti, Jr., who lives in Paris with his wife Ileana de la Guardia, daughter of Tony, another enthusiast, who was executed by firing squad. The name, Olga Finlay, does not ring a bell in his memory of his father’s entourage at Prensa Latina, the company that was Olga’s first noticeable commitment to revolutionary propaganda.

I also communicate with people in Santo Domingo, and this is a communication in which I have to be more tactful. Marianela Boán lives there, Ángel’s daughter, whose closeness to Olga makes me think that between them there could have been others sorts of revolutionary prancing about. Marianela is a legend of contemporary dance in Cuba. The DanzAbierta company she founded in 1988 revolutionized Cuban contemporary dance. Marianela has limited memories of the few years she lived together with her father. Everyone has a story, but Ángel Boán’s was brief and luminous. Ángel, like the Finlays, had left Cuba during the Batista years. But he wasn’t content with only being anti-Batista. He also maintained a polemic with Fidel Castro in 1955 about revolutionary strategy. There were two articles in which he challenged the young leader that none envisioned as a future bigwig. They appeared in Bohemia magazine and were titled “Fidel, Don’t Do Batista a Service” and “We Serve Cuba, Those of Us Who Avoided a Useless War” on November 13 and 27, 1955. Fidel responded to him, in the same magazine, with another equally inflammatory piece: “I Serve Cuba. Those Who Do Not Have the Courage to Sacrifice Themselves.”

The controversy between the brave journalist and the future Commander-in-Chief of the Rebel Army did not prevent Boán from being a major player in the journalism of the Revolution’s first years. His responsibility for the Prensa Latina office in New York, a key tool in the hydra of revolutionary propaganda, attests to this. Dragged along by his profession and the dizzying history of those years, Ángel Boán lost his life in Algeria in a traffic accident on July 18, 1963, when he was accompanying Ernesto Guevara, the Argentine revolutionary who went down in history under the nickname of “Che.”

I ask Marianela Boán what she remembers about those years and, above all, if she is familiar with the “Olga Finlay” who was always so close to her father during those months. “In 1961 I was 7 years old, and I have no clear information about daddy during those times,” Marianela informs me. And she adds to settle the question: “I don’t know anything about Olga Finlay either. At that time, he was married to my mother, and we lived with him in Washington and NY for a while.”

Olga Finlay left the United States on a ship that arrived at the port of Havana on June 22, 1961. She traveled with her parents, Enrique and Nena, and Ángel Boán, her boss. Everything went very fast in those months. The speed of revolutions is of many revolutions. Hurricane over sugar, is the title of a book by Sartre, one of the signatories of the paid appeal to the New York Times.

Olga’s American adventure, which lasted a little over ten years, was coming to an end. Although that’s a figure of speech.

* * *

(Playlist #6: El Son de la alfabetización, by Carlos Puebla) On June 23, 1961, the newspaper Revolución printed a four-column chronicle on the arrival of the ship Covadonga at the port of Havana loaded with “repatriates,” that is, Cubans returning to revolutionary Cuba after their exile in the United States. Yes, they were called “repatriates,” like the Cuban emigrants of the last years who step on the island to inherit or buy the future in pieces. Even in the entries of the most neutral of glossaries, Cuba’s history in this last half century is as round as a baseball, and its skin is as wounded as it is held together by seams and stitching.

The piece in Revolución is signed by Vicente Cubillas with photos by Liborio Noval. It is the same Cubillas who six years earlier had written a brief story on Fidel Castro’s meeting with exiles in New York in Bohemia. In it Cubillas describes the different groups of emigrants “came out in droves united in a solid block for the first time in the city of Hudson to stage their resistance to General Batista’s government.” Fidel, amnestied in 1955 and preparing his insurgent return to Cuba, had gone to ask for money and political support from the exiles. At the end of the event, according to Cubillas, “a recording of a speech by Eddy Chibás, the unforgettable orthodox leader, was played, and the audience listened reverently, standing on their feet.” How do we know if the Finlays attended the rally that afternoon at the Palm Garden, on 52nd Street and 8th Avenue? Was that the day they were definitively seduced by Fidel? Palm Garden, by the way, not to be confused with the Palm Court where the profiler Cobb would have tea with the young Olga Finlay, although both scenarios were inspired by the very tropical palms.

In the flaming chronicle of Revolución, the arrival of the Finlay family is a big deal. Imagine the stampede in those weeks and months. Many elegant and well-known people were leaving Havana, and seeing the very elegant and acclaimed Finlay family arrive, steeped in lineage, was cause for celebration in the AgitProp chapter. Let me quote at length here, because this is the journalistic prose of the nascent Revolution, the seed from which the twisted tree will grow later. I would like to fisk this childish prose, but I won’t. It is 1961, and it goes like this:

“Olguita Finlay could not wait to be in Cuba.

“The slowness of the Covadonga weighed on me” says the great-granddaughter of the illustrious Cuban sage Carlos J. Finlay. “I would have liked to put on my seven-league boots to see myself in my homeland in the blink of an eye.”

The pretty young Cuban woman, resident for ten years in New York and employed in the offices of Prensa Latina in that Babel until recently, has returned accompanied by her parents, Enrique Finlay, and Nena Saavedra.

“The situation was unbearable for us there,” she says. “My father and I worked on the Fair Play for Cuba Committee and we were ‘marked’ by the FBI, the CIA and every pro-government henchman there. The cops made repeated visits to our house with threatening gestures and phrases, and we understood that we had to get away as quickly as possible.

The Finlays are part of the contingent of 160 Cuban repatriates who arrived in Havana yesterday aboard the Spanish steamship Covadonga from New York after shaking off the dust of the sidewalks of Manhattan, poisoned by imperialist viciousness.

The Morro lighthouse keeper was surely the first to hear the jubilant cries of these compatriots who are returning to their homeland on their own free will, fed up with so much social rot and so many despicable worms sheltered under the folds of the Statue of Liberty’s robe.”

* * *

Let’s momentarily stick with Revolución, the fiery newspaper. There’s a family photo on the dock. Nena and Enrique are smiling, and Olga is very happy, her chin seeking a springboard or support on Ángel Boán’s shoulder. The caption reads: “The Finlay family wearing their happy little Cuban flags pinned to their chests greet their return to their homeland with smiles. Enrique is the grandson of the illustrious Cuban scholar who discovered the transmission of yellow fever by mosquitoes. His daughter Olguita, collaborator with the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, was threatened by the FBI. With them, the comrade Ángel Boán, from Prensa Latina.”

With the words “the transmission of fever,” the newspaper greets the repatriates, returning to their homeland heaving with joy. It’s both incredible and obscene, especially if one thinks that the Covadonga went down in the Revolution’s history for the next voyage it undertook through Cuban history’s waters, one sinister day in September 1961 when, three months after unloading the Finlay, it carried on its bridge and in its belly 131 priests expelled by the new regime. Don’t think I’m exaggerating, because considering this topic, Job and his whale could appear to me! A testimony: “The captain of the ship, who was a real gentleman… gave each of us a blanket to sleep in the holds,” Monsignor Agustín Román, one of the reluctant Catholics who boarded the Covadonga, said years later.

* * *

(Playlist #7: ¿Dónde estabas tú?, by Benny Moré) Those were busy weeks full of events, as we have already seen. Dragged along by the whirlwind of history, all those people moved, or were moved, at many, variable revolutions per minute, like Manolo Saavedra’s records. Less than two months after the ship that brought the Finlays from the United States anchored in Havana Bay, in a Europe where the frontier of freedom was drawn once again, as if on stage, traced by a fingernail or a bayonet on a continental map, the most absurd event in the history of that segregation took place. But this thing, made of a stone and cement, was hardly a performance. On the night of August 13, 1961, the Berlin Wall was erected. That same day, by the way, Fidel Castro also celebrated his 35th birthday.

Olga, as we have seen, was not lying about being “marked.” What she could not foresee was the course that the nature of the expression “pro-government henchmen” would take in the next half century of Cuba. Officials of the Cuban Institute of Friendship with the Peoples (ICAP) were waiting on the dock for “these Cubans who have been forced to escape from the clutches of the Empire,” Revolución added. The Finlays who decided to return were certainly not left stranded, and they found shelter, making a home in a nice residence on Línea Street in Havana, not far from the sea that protests against the seawall. A spacious house, with a stone façade and a hedge that protects it from the curiosity of passersby. I seem to remember that it used to belong to a doctor, although this seems a supreme display of circularity.

Olga immediately began to work in the office of Raúl Roa, Sr., the Minister of Foreign Affairs. In a way, since Olga already traveled to Cuba from New York to receive instructions from Vice Minister Fernández Font, upon her return she continued her work for the political machinery of promoting the Revolution abroad. Minister Roa, her new boss, was the father of the officer who would have given the check to the Fair Play for Cuba Committee, so everything stayed in the family there. And others were being formed! It was in Roa’s office, as Cristina Martínez Finlay tells me, that her mother Olga soon met Cecilio Martínez, a young man also repatriated to Cuba after his exile against Batista. They would marry a few weeks later, and the Minister officiated as witness of the wedding. It was meant to be, then, as Cristina said, “He was the matchmaker!” Cecilio was returning from Mexico and according to his service record in the MINREX file, to which we will return shortly, between 1959 and 1960, before entering the diplomatic service, he was “Political Instructor” in the Rebel Army and “Controller” on Channel 12 on the TV. A great metaphor of what was coming for Cuba was that takeover, by the way. Channel 12, with its office and studio in the Havana Hilton Hotel, was the first channel to broadcast color programming on the island and in much of the world as well. Inaugurated on March 19, 1958 by Cuban television magnate Gaspar Pumarejo, its life was brief. Barely a breath. The revolutionary “intervention” led Channel 12 to broadcast in black and white first and then to fade to black and disappear.

* * *

The Finlays return from New York in June 1961, having lived in the Big Apple for twelve years. For Olga, half of her life. The adult half. These were times of revolutionary effervescence for those who lived them in New York: the FPCC had struck a good blow and planted a rotten tree from which ripe fruit would fall for decades. Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s “One Thousand Fearful Words for Fidel Castro,” the left dancing the conga to the Cuban alternative, the October Crisis and the Bay of Pigs, with which Cuba would take possession of the centrality it longed for, were about to take place, the books of Waldo Frank, Wright Mills, and Sartre… The revolution was creating a discourse upon which to consolidate itself, and there were a lot of people pouring shovels of concrete on that plinth. It is a moment of horror, but also of tremendous beauty of passages in opposing directions. Some leave, while others return. The country is about to split in two. Well, it is already split. Although a single, unified party is soon coming: “Elections, what for?” cried the people with butterflies in their bellies. In addition, the newspaper, Revolución, merged with Hoy, and there’d soon be a Granma, filled with news about the sugarcane harvests and worms, brother countries, and imperialist threats. The Revolution is synthesis. It’s a reduction. From there to scarcity, there’s just one step.

As I said before, it’s easy to see all this from the perspective of the present, already knowing what the Revolution smells like, with your nostrils full of the stench from its rotten history, especially after so much time has passed. The epitome of macho heroism and sterile sacrifice. All the exceptionality bullshit. But don’t get excited: knowing it back then would’ve been knowing too much or knowing it by taking the Reader’s Digest shortcut. Quique and Olga didn’t take those shortcuts. They were on the straight path of history during the decades they lived through.

Let me tell you something in advance as you may be getting dizzy among so many enthusiasts of that Revolution and its social chronicle dressed up as Cold War literature. Many years later, one night in the early nineties, Carola and I were sitting on the little wall of the house next to the Finlays, who’d returned from New York. Havana was in turmoil, and there were people loitering around the building of what was then still the U.S. Interests Section, three hundred meters from that house. We were nurturing the possibility of joining them to escape from Cuba. Olga and Enrique, in that order, had died a few years before. Some trucks came rushing up and driving against the traffic along L Street. Some men got out of them, armed with sticks and corrugated iron bars, rebars, and ran in all directions. Half a dozen did so toward us. “You, what are you doing here?” they asked, brandishing their paramilitary truncheons. “Nothing, getting fresh air, because we live around here,” we said with all the insolence that fear allows us. “The street belongs to the revolutionaries!” the barbarians shouted. And we retreated into the house, the same house to which the Finlays, who were fleeing from the “henchmen” of New York, returned to. If those people wanted control of the street, and felt like scratching and beating people up for it, let them have it.

During that season of hell, near that very house, the poet Ramón Fernández Larrea wrote a poem I’ve always liked very much, “I Never Sang on Broadway”: “Never be late for the revolutions / they will have distributed the love / and you will have to ask who is last in the painful long line / with a wrinkled suit and a tie.” That other street, precisely, the Broadway that crosses another island and which she has lived alongside for the past twenty years, Carola Martínez Finlay would make her own since she arrived in New York at the dawn of the new century. So, all things considered, yes, the streets belong to the revolutionaries.

* * *

It is not difficult to imagine the enthusiasm of young Olga back in Cuba. Her collaboration with the Ministry now takes on a greater dimension. She works in the Minister’s office, but she also goes down into the thick of field work. We see her serving as the receptionist who sifts through other people who were curious about the Revolution. She appears, once again, in the chronicle of the trip to Cuba made by another activist of a different sort than that of the African Americans of the FPCC: specifically, in the account of Dorothy Day, a free electron with anarchist roots who later shifted to a radical Catholicism. She made her pilgrimage to this new Cuba and refers to having met with Olga Finlay when she went to request credentials from the MINREX. With regard to Olga and the rest of the welcoming committee, Day states, in no uncertain terms, that they played a filtering role, given their knowledge of the typical American sympathizer: “They asked me questions about the States… and they all most hopefully asked me what I wanted to see in Cuba,” she recounts in “On Pilgrimage In Cuba, Part II,” travel notes she published in The Catholic Worker in October 1962.

But Olga Finlay would not work for long in Minister Raúl Roa’s office. But the young “repatriated” couple, in which Olga was very, very young, and Cecilio, born twelve years earlier, was somewhat less young, did not take long to pack their bags again and leave for Stockholm, where Cecilio had been put in charge of the Cuban Embassy to the Kingdom of Sweden. They traveled with little Carola, their first daughter, who was kicking travelers’ ankles and the seat in of front of theirs, on the long flight with a stopover probably in Barajas, obligatory in the commercial aviation that linked Cuba with the world located on the sunniest side of the Berlin Wall in those years. Olga gave birth to three other children in Stockholm.

Enrique Finlay, the Sage’s grandson, traveled with them. The traces of his professional career faded after spending a few years in the Swedish capital with his wife and daughter. In fact, there is not much trace of it in Sweden either. He seems to have held the post of Consul in Denmark, although also in his case, as in Olga’s, the MINREX archive, whose doors have been kindly opened to me by Marlenis Pozo, a specialist in document management, is sparse. In fact, neither in the archive nor in the memory of many of the survivors of those years does Enrique exist.

Nevertheless, still in Sweden, some references place him in the trail of his activities related to the Americans of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee. Thus, there are testimonies of his relationship with the Black Power activist Robert F. Williams, who organized some of the Committee’s acts in New York and, according to Cuban-born ethnologist and political scientist, Carlos Moore, would have sent a letter to Minister Raúl Roa asking for the intervention of Cuban troops in the south of the USA “to liberate the blacks from the Ku Klux Klan.” Williams, like some other Afro-American leaders or “soldiers” ended up in self-exile in Cuba. In his case, he arrived on the island in 1961, although we already saw him visiting the island with Olga in July 1960. Established in Cuba, his relationship with the high and even the middle revolutionary hierarchy seems to have deteriorated very quickly, so he ended up in the very Cuban situation of having his hands full trying to obtain a departure permit from the island. According to Ronald J. Stephens in “Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition: Robert J. William’s Crusade for Justice on Behalf of Twenty-two Million African Americans as a Cuban Exile,” it was Enrique Finlay, in fact, “a native Cuban… (who) knew Williams from his FPCC in New York,” who, from Stockholm, arranged an escape route for the African American activist through China.

Nothing else is revealed in the archives about Enrique Finlay. His centrality in the row of the five Finlays was an optical illusion. We will not bother him again on this slope downward where this story is heading to a corner of the San Isidro neighborhood in Havana. That’s where Carola Martínez Finlay, the girl who first saw snow in Sweden in the winter of 1964, the great-great-granddaughter of the Sage, stood on a corner of Damas Street disgusted by one of the many acts of repudiation that the Cuban state dedicated to the artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, before sending him to prison on July 11, 2021.

* * *

(Playlist #8: Jag Var Så Kär, by Agnetha Fältskog) In Mapa dibujado por un espía (2013, Map Drawn By a Spy, 2017), one of his posthumous books, Guillermo Cabrera Infante tells the story of a trip to a meeting in Madrid with the heads of the Cuban embassies in Western Europe. Also summoned to this meeting was the head of the Cuban Embassy in Stockholm, who naturally was accompanied by his wife. That the three of them coincided in Madrid during that winter is attested to by the CIA’s record of Cuban officials arriving at Barajas airport. Cabrera Infante had already said that it was a big meeting and, indeed, a CIA report gave an account of the parade of Cuban ambassadors through the corridors of the Spanish capital’s airport between February 4 and 7, 1965. The first in the tally are the diplomats arriving on a flight from Brussels: “Cecilio Martínez, Min(ister) Stockholm, and wife Olga Finlay Saavedra.” The next is “Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Acting Charge Brussels.” The Finlay family memoir records Guillermo having confided to Olga and Cecilio, with whom he maintained an affectionate relationship, his displeasure with the path the revolutionary process was taking and the situation of harassment he was suffering at the Embassy in Brussels. This was another milestone on the road that would later lead him, after the trip, to bury his mother, something he narrates precisely in that book, renounce returning to Havana, and remain in Europe, where he would end up becoming an icon of counterrevolutionary culture.

The Finlay family returned to Havana in the late 1960s, when the Revolution was already showing its fangs. Those were difficult times in the MINREX, whose officials were suspected of adopting bourgeois ways, and many of them were sent to destinations within the country, where they could become familiar with the reality of those who were both beneficiaries and victims of the “good news.” A part of Cecilio Martínez’s Service Record that I obtained from the Ministry’s archives states just that. Below is a list of the responsibilities and tasks he carried out beginning in the year of his collaboration with that entity:

1960-1961: Emba Cuba China, I Secretary.

1961-1962: MINREX, J. Dept. U.S.A. and Canada.

1962-1964: MINREX, Director of the USA and Canada.

1964-1968: Emba Cuba Sweden, Chargé d’Affaires with the rank of Minister.

1968-1970: MINREX, Service Commission in Agriculture.

1970-1972: Department head in the Americas Directorate.

1972-1973: Micro-brigade.

Before creating this list, the report’s author praised the diplomat’s work for how he participated on the “concrete” level in the new regime, something that the revolutionary government demanded of its soldiers whom they had armed with both a “non-aligned” syllabus and a Rolex. “He participated in the 1969 and 1970 sugarcane harvests. He spent one year in the MINREX micro-brigade helping to construct apartment buildings, in addition to other productive tasks.”

In the late sixties, the Revolution was already definitively and drastically turning into an authoritarian nightmare, and I don’t know what became of Olga Finlay’s dreams. Some of her children, whom I asked, don’t know for certain either. She didn’t part ways with the Revolution in any way, however. From the Swedish capital, Olga and Cecilio returned with Carola and the three babies she gave birth to in a clinic in the Danderyd municipality, to the north of Stockholm, the same one where the Embassy of the Republic of Cuba was and still is. They also bought a big car for a big family: a wonderful light blue Volvo. A 122S Wagon, the ‘67 model; one of those that Cubans call “pisicorre.” It was a somewhat outlandish car in a Cuba where hardly any new vehicles had been arriving since 1960. A jewel, indeed. Many years later, in Havana during the Special Period, the family sold the car to a guy who worked in the Volvo office. A beautiful collector’s item. Later on it could be seen in the neighborhood of Vedado, but “for about 22 years now, there’s been no trace of it,” Olga’s sons informed me.

The youngest of them, Camilo Martínez Finlay, conveyed this to me from Havana, where he died on October 22, 2021, when I was finishing writing these pages that I now dedicate to his memory. Due to an accident with another beautiful and powerful car, a Mercedes-Benz that crashed into a palm tree on Rancho Boyeros Avenue, he became disabled, but that did not prevent him from becoming a go-to man in Havana’s private hotel industry these past two decades. An ESPN report described him in September 2016 as a successful businessman, applauding his lodging and bar as the only ones in the entire city perfectly adapted for guests with severe handicaps caused by spinal cord injuries such as the one he, himself, suffered.

The eldest of Olga’s sons wasn’t about to surrender to anonymity either. The first of those to be born in Sweden—a different Finlay— might be called “the black sheep.” Cecilio, Jr., “Chilingo,” as he was known, also left his trace in the history of his neighborhood, his friends, his time. That of a guy who already lived outside Cuba and its narrow frameworks even before he actually left it behind. Trafficker of everything and with everyone, prisoner and fugitive and again prisoner and again fugitive. Like so many other high-ranking Cuban officials, the Finlays did not have to look too far to get proof that the Cuba built for the children of the revolutionaries was useless even for their own children. The proof was there for them to see. Many years ago (and you’ll understand why I’m being cautious at this point with data), I received the only phone call I’ve received from Villa Marista Cuban State Security headquarters. “We inform you that citizen ‘X’ is detained here and that you can bring hygiene items to him between 8:00 and 10:00 in the morning,” a woman’s voice told me. “X,” of course wasn’t the name of my friend Cecilio. The name I was given was a different one, but the person waiting for soap and a toothbrush with a smile on his lips was him. He had given my phone number to confuse his jailers. The next day he had soap and a towel in prison. He outwitted them to the end, and a few years later we had a few beers in an apartment in Barcelona, on his route to the United States, the country where his mother was an “American girl” for a few years and where he is now and forever the proud father of a formidable “American boy.”

Olga Finlay left the Foreign Ministry in 1977 without any known reason, but what’s certain is that ten years after returning to Cuba and four years after the Embassy in Stockholm, she left, as did her husband, the building where Cuba manufactures grievances and fallacies with more success than it does manufacturing soap or butter. According to the file in the archives, Olga Finlay worked in the Department of International Organizations for a few years, and from 1975 onwards, she was “Head of Section of the International Treaties Area.”

* * *

(Playlist #9: Pólvora mojada, by Beatriz Márquez) When she left the Ministry, more or less disappointed, Olga neither squandered her political capital, nor her revolutionary enthusiasm. They served her to charge toward the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC), one of those mass organizations that Eastern European socialist regimes were so fond of, since they were, at once, a breeding ground for enthusiasm and a grill for the ever-burning barbecue of control. This, in particular, was not just any organization, since its president was Vilma Espín, the sister-in-law of the head of the Revolution. The fact that Olga Finlay held a position as important as being responsible for foreign relations of that organization with an office in the large house of the FMC headquarters on Paseo Street and, to a large extent, was also in charge of Vilma’s activity with foreign visitors, shows that she hadn’t lost the confidence of the revolutionary leadership and much less, that of the agents who verify the environment around leaders.