Lydia Cabrera was part of the Africanist movement almost since its origins, and true to the excitement she felt upon reading Césaire, she translated and studied Antillean blackness and Yoruba poetry from the latter half of the twentieth century.

The Cuban anthropologist, writer, and artist Lydia Cabrera (1899-1991) was involved in the Africanist movement from its origins in interwar Paris. The publication of her “Contes nègres de Cuba” (1936) by Gallimard, translated into French by the novelist Francis de Miomandre, had a discernible impact on the community of Antillean and African intellectuals residing in the French capital. The translator, Miomandre, had previously translated novels by the Venezuelan writer Teresa de la Parra, who was also based in Paris and a close friend of Cabrera.

Parra and Cabrera had met in Havana in 1927 when the Venezuelan attended the Inter-American Journalists Congress that year. Parra’s novel “Ifigenia” was a “diary of a young lady who wrote because she was bored,” reminiscent of Cabrera’s series of chronicles “Nena en sociedad,” published in the magazine “Cuba y América” between 1913 and 1916. Parra’s novel was constructed like a diary but also as a series of letters between friends María Eugenia Alonso and Cristina de Iturbe, similar to the correspondence between the Venezuelan and the Cuban that would later be observed.

Along with “Ifigenia,” the “Memorias de Mamá Blanca” must have been another decisive reading for Cabrera. This work not only reproduced the tone of testimonies but also delved into an exploration of Venezuelan popular culture, especially through the character of the elderly black man Vicente Cochocho, whose influence is evident in Cabrera’s work. The correspondence between the two writers, regarding Cabrera’s trip to Havana from Paris in 1930, as noted by Isabel Castellanos, precisely describes the beginning of the research that supports the writing of “Cuentos negros” and “El Monte” (1954).

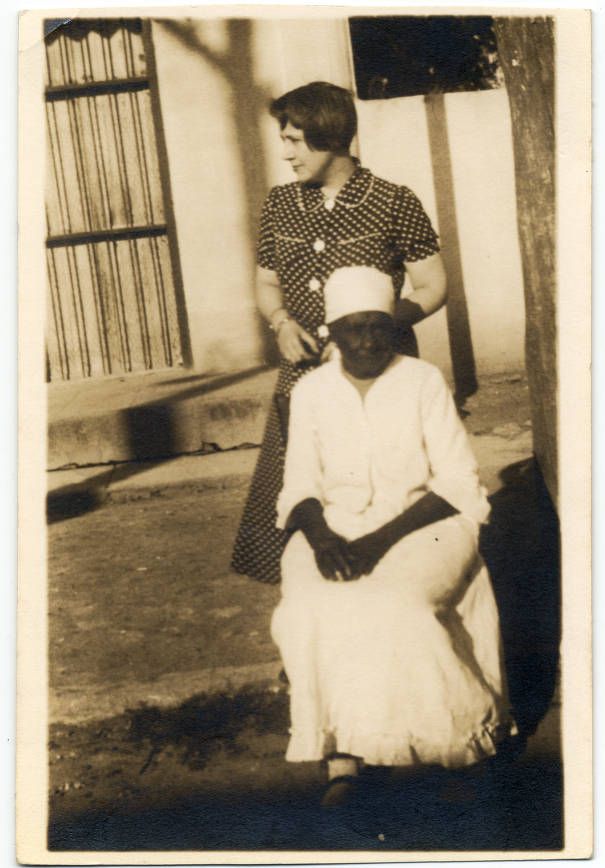

In a letter from Cabrera to Parra during those years, the Cuban recounts her visits to the black neighborhood of Pogolotti in Havana, where she meets her informants: José Calazán Herrera (Bengoché), Teresa Muñoz (Omí Tomí), Calixta Morales (Oddedeí), and Leonorcita Armenteros, among others. These Black Cubans would be a significant source for much of her ethnographic, literary, and visual work, as Cabrera was also a painter, and her translation vocation extended not only to the transcription of Afro-Cuban culture but also to her own versions of Antillean and African poets like Aimé Césaire, Léon-Gontran Damas, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Birago Diop, David Diop, Gabriel Okara, Christopher Okigbo, and Wole Soyinka.

Some of those poets, such as the Martinican Césaire, the Guyanese Damas, and the Senegalese Senghor, who would later become the president of his country, also lived in Paris in the thirties and were involved in Africanist youth projects in the French capital, such as “Légitime Defense” (1932) and “L’Estudiant Noir” (1934). Cabrera would firsthand experience not only the Africanist movement but also its impact on the French literary and pictorial avant-garde through the works of Apollinaire and Breton, Derain and Matisse, Picasso and Braque.

“Contes negres” was perhaps the best-positioned Cuban text in Parisian blackness in the thirties. However, its reception was not without dissonance from the beginning. While Miomandre appreciated the role of fiction in the text, Fernando Ortiz, in the prologue to the Cuban edition of 1940, dismissed its ethnographic value in terms of religious or cosmovisive archaeology, reducing it to a “rich contribution to Cuban folk literature, which is black and white.” In his note for “Carteles” in 1936, Alejo Carpentier accurately warned that “it would be a mistake to believe that the writer has contented herself with transcribing folklore in her narratives.”

Carpentier’s chronicle, “Cuentos negros de Lydia Cabrera,” was one of the many self-censored in the Cuban and Mexican editions of the anthology edited by the Cuban writer and critic José Antonio Portuondo in 1976. The self-censorship was due to Cabrera’s exile in Miami after 1959 and her rejection of the political system established on the island. But in 1936, in Paris, Carpentier had read that “mysterious and harsh book, full of dark rebellions” with precision.

These last words, “dark rebellions,” touch on one of the keys of “Cuentos negros.” Many of these stories, like the classics of Western political thought (Locke and Rousseau, Hobbes and Montesquieu), started with a description of the “state of nature” and its transition to the formation of civil government through a social contract. It spoke, for example, of a time when there was only one man (Yácara) on the earth (Entoto), living on a hill (Cheché) next to the sea (Kalunga). And it also spoke, in the story “Taita Jicotea y Taita Tigre,” of a time before that man when “everything was green,” and “Obá Ogó created man by blowing on his dung.”

One of those early men “ascended to the sky on a rope of light” and approached the sun too closely. This Icarus “burned and turned black from head to toe,” giving rise to “the first Black man, the father of all Black people.” Another man went to the moon “riding a horse-bird-alligator-cloud-small,” froze with the cold water in the moon’s eye cistern, and whitened, becoming the first white man. Black people, the story adds in a binary tone, are the owners of joy, and whites of sadness.

In another story, the history of Obá Olorún is narrated, father of the sky and the earth, born as brothers and living in peace for a long time. The earth worked and revered its brother, the sky, and he sheltered and protected his sister, the earth. In another, titled “La carta de libertad” (The Letter of Freedom), reference was made to a time immemorial when “animals spoke, were good friends with each other, and understood humans.” Then the dog, the cat, and the mouse were inseparable.

All these representations of the state of nature, closer to Rousseau than to Hobbes, resorted to images of a lost paradise. War, a central theme in Lydia Cabrera’s “Cuentos negros,” appears as a consequence of the emergence of an element of discord that breaks the harmony. Hostilities between the sky and the earth, the dog and the cat, the mouse, the turtle, the deer, the rabbit, and the tiger. The black and the white are the result of that loss of the natural state and an unjust social contract based on the enslavement of the other. The influence of Christianity in the doctrines of the social contract is well-known, both in Hobbes and Rousseau, which makes it intriguing that Fernando Ortiz suggested not giving importance to the religiosity of Cabrera’s tales. However, it seems that Oggún’s interventions in the “sacred mountain, greedy for its treasures, a dangerous domain of malevolent forces” that should not be invoked with evil actions are central to these stories.

The breaking of the state of nature is treated similarly to the Fall in Genesis, but its meaning, as in Rousseau, is more connected to the imposition of dispossession and slavery:

“Misfortune was not a thing of this world: for a time without cruelty – during that time that no one lived and everyone yearned for – animals and humans still sigh. Cruelty was not of this world. The evil spirits that cause the most abject physical sufferings and that invisibly and cunningly enter through the eyes, or vaporize to be inhaled, had no name because they did not exist. No one fell ill. Desirable death – clean and sweet – was announced with a gentle sleep.”

Contrary to Hobbes, war, with its agonistic mentality, was the work of the social contract, not the state of nature. All those plots of harmful plants and wicked sorcerers, endokis and chicherekús, evil eyes and curses were reactions to the war. In the discomfort of that condition, brilliantly depicted in the story “Carta de libertad” (Letter of Freedom), Carpentier may have found a glimpse of the “dark rebellions.” Among the various paths to freedom – letter, manumission, patronage, maroonage – the dog in the story had chosen the first, and the narrator reproaches him in the final scene, where he lies at his owner’s feet, licking his hands.

Cabrera may have noticed the same dark rebellion when reading Aimé Césaire’s “Cahier d’un retour au pays natal” (1939), which she translated for the Havana edition of 1943. Thirty years later, in exile during a residency in Madrid, she revisited that translation, adding her versions of Damas, Senghor, the Diops, Soyinka, and other Caribbean and African poets, specifically Yoruba poets from Senegal and Nigeria, in a lengthy essay for the Revista de la Universidad Complutense titled “Notas sobre África, la negritud y la actual poesía yoruba” (1975).

In this essay, she confessed the fear that these verses of Césaire caused her in her youth: “negritude stands / the blackness seated / unexpectedly standing / standing in the hold / standing in the cabins / standing on the deck / standing in the wind / standing in the sun / standing and free.” It is interesting to note that in her 1943 translation in Havana, Cabrera presented the first line as “negritude stands.” Still, in the 1975 version in Madrid, she translated the word “négraille” as “negritude” to reinforce the “neologism” created by the three founders of the Negritude movement in interwar Paris.

Lydia Cabrera’s translations of Wole Soyinka from English, especially the poems “Idandre” and “Estación,” were published ten years before the Nigerian poet was awarded the Nobel Prize. Among the electronic traces of Soyinka’s passage through the Casa de las Américas, the Conjunto Folklórico Nacional, and the Escuela de Cine de San Antonio de los Baños, there is none that records the inevitable memory that, a few miles north of Havana, lived a Cuban writer, anthropologist, and artist who translated these verses into Spanish: “Oggún the solitary saw it all, the secret veins / of matter and the veins that surround it. / The consumed lightning of Changó served as his hammer’s head. / His fingers touched the center of the earth, and it yielded.”